Egyptian Ka Bull Alphabet Ankh Symbolism

An excursus on the Egyptian word nTr

The word death comes from Old English dēaþ, which in turn comes from Proto-Germanic *dauþuz (reconstructed by etymological analysis). This comes from the Proto-Indo-European stem *dheu- meaning the “process, act, condition of dying”.

Die: mid-12c., dien, deighen, of sentient beings, “to cease to live,” possibly from Old Danish døja or Old Norse deyja “to die, pass away,” both from Proto-Germanic *dawjan (source also of Old Frisian deja“to kill,” Old Saxon doian, Old High German touwen, Gothic diwans “mortal”), from PIE root *dheu- “to pass away, die, become senseless” (source also of Old Irish dith “end, death,” Old Church Slavonic daviti, Russian davit’ “to choke, suffer”).

Dead: Middle English ded, from Old English dead “having ceased to live,” also “torpid, dull;” of water, “still, standing,” from Proto-Germanic *daudaz (source also of Old Saxon dod, Danish død, Swedish död, Old Frisian dad, Middle Dutch doot, Dutch dood, Old High German tot, German tot, Old Norse dauðr, Gothic dauþs “dead”), a past-participle adjective based on *dau-, which is perhaps from PIE *dheu- “to die”.

The Egyptian hieroglyph for the t phoneme represents a “bread bun”. The word-final -t in Egyptian usually represents the feminine gender. It is one of the most frequently used sign in hieroglyphic writing. Besides alphabetic-t, the bread bun is used for words that are feminine, as an end qualifying determinant, often shown before other qualifying ideograms or determinants in the hieroglyphic word block-(quadrat hieroglyphic block).

Egyptian hieroglyph: Bread bun, loaf of bread: phonogram t; logogram bread; abbreviation of father; Thoth (Djhwty). The Sanskrit based glyph is tu-ng rqUx, which means ‘Vaulted, high, elevated, tall, lofty, prominent, long, chief, strong, passionate, a mountain’.

The Sky hieroglyph

The ancient Egyptian Sky hieroglyph, (also translated as heaven in some texts, or iconography), is used like an Egyptian language biliteral-(but is not listed there) and an ideogram in pt, “sky”; it is a determinative in other synonyms of sky. For the language value hrt, it has the phonetic value hry. It is often written with the complement of its component values of “p”, and “t”, in a hieroglyph composition block meaning “pt”, or commonly ‘pet’.

The Sky hieroglyph can be found in iconography with the gods, especially Ra as referencing the Lord of P(e)t, (Lord of Heaven), and the God’s ownership of Pet. The Pharaoh is often equally named as the Lord of Pet. Some ancient Egyptian names using the sky hieroglyph are Petosiris, the high priest of Thoth at Hermopolis, and the god Petbe, the god of revenge.

The simple ‘vault’ of the sky hieroglyph has variants that are ligatured with it. Though the sky hieroglyph is used as pt, in the Coptic alphabet, for the Coptic language, (the follow-on to the Egyptian hieroglyphs), the spelling of the “sky” is “pe” in Coptic. Consequently, Budge’s 2-volume dictionary lists the sky hieroglyph under “pe-t”

In the short P word section in the Egyptian dictionaries, the end of the P’s has the pd, and pdj. In the languages the d’s and t’s are listed together; they are the unaspirated and the aspirated. (See d, and dj, the hieroglyphs for “hand” and “cobra”.)

The pd is represented by ‘feet’, and parts of them, and ‘running’, and the hieroglyph for ‘extend’, -(similar to a bow). Many of the entries also refer to items about the bow, i.e. “stringing a bow”, etc. The pdj then refers to bowmen, etc., and especially the Nine bows. The archers of the 1350 BC Amarna letters, the archers (Egyptian pitati) get their name of ‘pitati’ from these related pd words.

Nut

Nut (Ancient Egyptian: Nwt), also known by various other transcriptions, is the goddess of the sky in the Ennead of ancient Egyptian religion. She was seen as a star-covered nude woman arching over the earth, or as a cow.

The pronunciation of ancient Egyptian is uncertain because vowels were long omitted from its writing, although her name often includes the unpronounced determinative hieroglyph for “sky”. Her name Nwt, itself also meaning “Sky”, is usually transcribed as “Nut” but also sometimes appears in older sources as Nunut, Nenet, Naunet, Nuit.

Nut was the goddess of the sky and all heavenly bodies, a symbol of protecting the dead when they enter the afterlife. According to the Egyptians, during the day, the heavenly bodies—such as the sun and moon—would make their way across her body. Then, at dusk, they would be swallowed, pass through her belly during the night, and be reborn at dawn.

Nut is also the barrier separating the forces of chaos from the ordered cosmos in the world. She was pictured as a woman arched on her toes and fingertips over the earth; her body portrayed as a star-filled sky. Nut’s fingers and toes were believed to touch the four cardinal points or directions of north, south, east, and west.

Nut appears in the creation myth of Heliopolis which involves several goddesses who play important roles: Tefnut (Tefenet) is a personification of moisture, who mated with Shu (Air) and then gave birth to Sky as the goddess Nut, who mated with her brother Earth, as Geb.

Nut and her brother, Geb, may be considered enigmas in the world of mythology. In direct contrast to most other mythologies which usually develop a sky father associated with an Earth mother (or Mother Nature), she personified the sky and he the Earth.

From the union of Geb and Nut came, among others, the most popular of Egyptian goddesses, Isis, the mother of Horus, whose story is central to that of her brother-husband, the resurrection god Osiris.

Osiris is killed by his brother Set and scattered over the Earth in 14 pieces which Isis gathers up and puts back together. Osiris then climbs a ladder into his mother Nut for safety and eventually becomes king of the dead. A sacred symbol of Nut was the ladder used by Osiris to enter her heavenly skies. This ladder-symbol was called maqet and was placed in tombs to protect the deceased, and to invoke the aid of the deity of the dead.

A huge cult developed about Osiris that lasted well into Roman times. Isis was her husband’s queen in the underworld and the theological basis for the role of the queen on earth. It can be said that she was a version of the great goddess Hathor. Like Hathor she not only had death and rebirth associations, but was the protector of children and the goddess of childbirth.

Because of her role in saving Osiris, Nut was seen as a friend and protector of the dead, who appealed to her as a child appeals to its mother: “O my Mother Nut, stretch Yourself over me, that I may be placed among the imperishable stars which are in You, and that I may not die.” Nut was thought to draw the dead into her star-filled sky, and refresh them with food and wine: “I am Nut, and I have come so that I may enfold and protect you from all things evil.”

Khenti (“foremost”)

The ancient Egyptian Water-jugs-in-stand hieroglyph is used as an ideogram in (kh)nt-(ḫnt). It is also used phonetically for (ḫnt). The water-jugs-in-stand hieroglyph is often written with the complement of three other hieroglyphs, the water ripple, bread bun, and two strokes, to make the Egyptian language word foremost, khenti.

As Egyptian “khenti”, foremost is used extensively to refer to gods, often in charge of a region, or position, as foremost of xxxx. Anubis, or Osiris are often referred to as “Foremost”, or “Chief” of the ‘western cemetery’, (where the sun sets).

Khenti-Amentiu, also Khentiamentiu, Khenti-Amenti, Kenti-Amentiu and many other spellings, was depicted as a jackal-headed deity at Abydos in Upper Egypt, who stood guard over the city of the dead.

Khenti-Amentiu is an ancient Egyptian deity whose name was also used as a title for Osiris and Anubis. The name means “Foremost of the Westerners” or “Chief of the Westerners”, where “Westerners” refers to the dead.

Osiris was associated with the epithet Khenti-Amentiu, meaning “Foremost of the Westerners”, a reference to his kingship in the land of the dead. As ruler of the dead, Osiris was also sometimes called “king of the living”: ancient Egyptians considered the blessed dead “the living ones”.

Thoth / Maat

Thoth (the reflex of Ancient Egyptian: ḏḥwtj “[He] is like the Ibis”) is one of the ancient Egyptian deities. Other forms of the name ḏḥwty using older transcriptions include Jehuti, Jehuty, Tahuti, Tehuti, Zehuti, Techu, or Tetu. Multiple titles for Thoth, similar to the pharaonic titulary, are also known, including A, Sheps, Lord of Khemennu, Asten, Khenti, Mehi, Hab, and A’an.

In art, he was often depicted as a man with the head of an ibis or a baboon, animals sacred to him. His feminine counterpart was Seshat, and his wife was Ma’at, the ancient Egyptian concepts of truth, balance, order, harmony, law, morality, and justice.

Maat was also the goddess who personified these concepts, and regulated the stars, seasons, and the actions of mortals and the deities who had brought order from chaos at the moment of creation. Her ideological opposite was Isfet (Egyptian jzft), meaning injustice, chaos, violence or to do evil. Pharaohs are often depicted with the emblems of Maat to emphasise their role in upholding the laws and righteousness.

After her role in creation and continuously preventing the universe from returning to chaos, her primary role in ancient Egyptian religion dealt with the Weighing of the Heart that took place in the Duat. Her feather was the measure that determined whether the souls (considered to reside in the heart) of the departed would reach the paradise of the afterlife successfully.

Thoth’s chief temple was located in the city of Ancient Egyptian: ḫmnw χaˈmaːnaw, Egyptological pronunciation: “Khemenu”, Coptic: Ϣⲙⲟⲩⲛ Shmun, which was known as Hermoû pólis “The City of Hermes”, or in Latin as Hermopolis Magna, during the Hellenistic period through the interpretatio graeca that Thoth was Hermes. Later known el-Ashmunein in Egyptian Arabic, it was partially destroyed in 1826.

Thoth played many vital and prominent roles in Egyptian mythology, such as maintaining the universe, and being one of the two deities (the other being Maat) who stood on either side of Ra’s solar barge. In the later history of ancient Egypt, Thoth became heavily associated with the arbitration of godly disputes, the arts of magic, the system of writing, the development of science, and the judgment of the dead.

He was the master of both physical and moral (i.e. divine) law, making proper use of Ma’at. He is credited with making the calculations for the establishment of the heavens, stars, Earth, and everything in them. He is said to direct the motions of the heavenly bodies. Without his words, the Egyptians believed, the gods would not exist.

In the underworld, Duat, he appeared as an ape, Aani, the god of equilibrium, who reported when the scales weighing the deceased’s heart against the feather, representing the principle of Maat, was exactly even. His power was unlimited in the Underworld and rivalled that of Ra and Osiris.

Duat

Duat (Ancient Egyptian: dwꜣt, Egyptological pronunciation “do-aht”, Coptic: ⲧⲏ, also appearing as Tuat, Tuaut or Akert, Amenthes, Amenti, or Neter-khertet) was the realm of the dead in ancient Egyptian mythology. It has been represented in hieroglyphs as a star-in-circle. The god Osiris was believed to be the lord of the underworld since he personified rebirth and life after death, being the first mummy as depicted in the Osiris myth.

The underworld was also the residence of various other gods along with Osiris. The Duat was the region through which the sun god Ra traveled from west to east each night, and it was where he battled Apophis, who embodied the primordial chaos which the sun had to defeat in order to rise each morning and bring order back to the earth.

It was also the place where people’s souls went after death for judgement, though that was not the full extent of the afterlife. Burial chambers formed touching-points between the mundane world and the Duat, and the ꜣḫ (Egyptological pronunciation: “akh”) “the effectiveness of the dead”, could use tombs to travel back and forth from the Duat.

Each night through the Duat the sun god Ra travelled, signifying revivification as the main goal of the dead. Ra travelled under the world upon his Atet barge from west to east, and was transformed from its aged Atum form into Khepri, the new dawning sun.

The dead king, worshiped as a god, was also central to the mythology surrounding the concept of Duat, often depicted as being one with Ra. Along with the sun god the dead king had to travel through the Kingdom of Osiris, the Duat, using the special knowledge he was supposed to possess, which was recorded in the Coffin Texts, that served as a guide to the hereafter not just for the king but for all deceased.

According to the Amduat, the underworld consists of twelve regions signifying the twelve hours of the sun god’s journey through it, battling Apep in order to bring order back to the earth in the morning; as his rays illuminated the Duat throughout the journey, they revived the dead who occupied the underworld and let them enjoy life after death in that hour of the night when they were in the presence of the sun god, after which they went back to their sleep waiting for the god’s return the following night.

Just like the dead king, the rest of the dead journeyed through the various parts of the Duat, not to be unified with the sun god but to be judged. If the deceased was successfully able to pass various demons and challenges, then he or she would reach the weighing of the heart. In this ritual, the heart of the deceased was weighed by Anubis against the feather of Maat, which represents truth and justice.

Any heart that is heavier than the feather was rejected and eaten by Ammit, the devourer of souls, as these people were denied existence after death in the Duat. The souls that were lighter than the feather would pass this most important test, and would be allowed to travel toward Aaru, the “Field of Rushes”, an ideal version of the world they knew of, in which they would plough, sow, and harvest abundant crops.

Netjer

Netjer” (net-CHUR, net-JAIR) is the Kemetic term for God. It is normally used in reference to the Self-Created One — the source of godhead from which the Names (the Many gods and goddesses) spring forth. You may see Netjer referred to as both Netjer and God in Kemetic Orthodoxy. “God,” unless the context is clearly stated to be about another religion, is to be understood to be the same as “Netjer.”

Phonetically, Netjer is spelled “nTr” (the capitalized “T” standing for a “tj” sound — in a fully realized transliteration font, this would be lowercased and underlined). Because not everyone is aware that the “t” with a line under it, or capitalized T in the Manual De Codage system of hieroglyphic transliteration, stands for the “tj” sound and not just a “t” sound, you may see other spellings for Netjer including “neter,” “ntr” and even “necher.”

The Kemetic Orthodox preferred spelling, as provided for us by Nisut (AUS), is Netjer. Further explanation can be found here. When referring to various aspects of Netjer, the “ancient Egyptian gods and goddesses,” we call Them “Names”, implying that, while a Name is a distinct personality and an individualized god Being, It is also still an aspect of the One Godhead of the Self-Created (e.g., “I worship Ra; He is a Name of Netjer.”).

It is transliterated as nTr, where the “T” represents a prepalatal stop usually rendered in Western speech as a “ch” sound. In their hieroglyphic, hieratic, and demotic scripts the Egyptians did not employ symbols representing vowels, so the most we can reconstruct from this ancient word are the consonants transliterated nTr. That is, as with so many words from the ancient Egyptian vocabulary, absent the vowels we cannot know for sure how nTr sounded as spoken in pharaonic times; hence “netjer.”

The Egyptian nTr seems also to have been intimately associated with the dead. Some have argued that nTr may have originally referred to the dead. The etymology and origin of the word nTr remains unknown, despite decades of attempts by linguists to try to identify cognates and other connections to Afro-Semitic languages, but its meaning is not a mystery. The Egyptians themselves left us an ample record of the word to examine.

Flagpoles

There are numerous ways the word was written in hieroglyphs when pertaining to gods, goddesses, or other divine concepts, and a number of different semantic determinatives developed through pharaonic history to help to clarify meanings; the most common determinative was, however, the pole and banner, which resembles a flag, the hieroglyph sign for “god”. Until recent times flagpoles were commonly set up outside tombs in North Africa and Sudan, reflecting a tradition seen in pharaonic Egypt going back into prehistory.

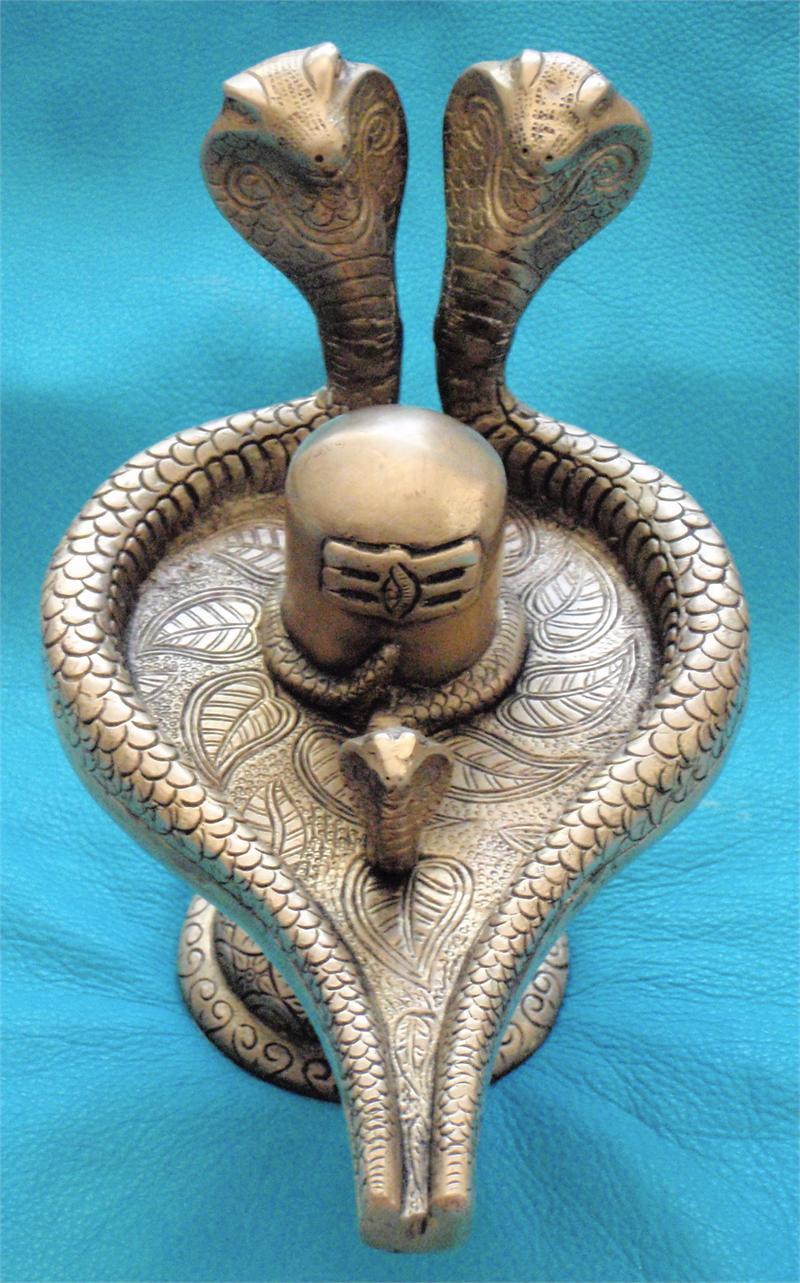

Wadjet

Wadjet (“Green One”), known to the Greek world as Uto or Buto among other names including Wedjat, Uadjet, and Udjo, was originally the ancient local goddess of the city of Dep. Wadjet was said to be the patron and protector of Lower Egypt, and upon unification with Upper Egypt, the joint protector and patron of all of Egypt “goddess” of Upper Egypt.

The image of Wadjet with the sun disk is called the uraeus (plural Uraei or Uraeuses; from the Greek ouraîos, “on its tail”; from Egyptian jʿr.t (iaret), “rearing cobra”), and it was the emblem on the crown of the rulers of Lower Egypt. The Uraeus is the stylized, upright form of an Egyptian cobra (asp, serpent, or snake), used as a symbol of sovereignty, royalty, deity and divine authority in ancient Egypt.

Wadjet was closely associated in ancient Egyptian religion with the Eye of Ra, a powerful protective deity. Much later, Wadjet became associated with Isis as well as with many other deities. Her image also rears up from the staff of the “flagpoles” that are used to indicate deities, as seen in the hieroglyph for “uraeus” and for “goddess” in other places.

Wadjet was depicted as a cobra. As patron and protector, later Wadjet often was shown coiled upon the head of Ra; in order to act as his protection, this image of her became the uraeus symbol used on the royal crowns as well. The uraeus originally had been her body alone, which wrapped around or was coiled upon the head of the pharaoh or another deity.

She was also the protector of kings and of women in childbirth. Wadjet was said to be the nurse of the infant god Horus, the child of the sun deity who would be interpreted to represent the pharaoh. With the help of his mother Isis, they protected Horus from his treacherous uncle, Set, when they took refuge in the swamps of the Nile Delta.

The “Going Forth of Wadjet” was celebrated on December 25 with chants and songs. An annual festival held in the city celebrated Wadjet on April 21. Other important dates for special worship of her were June 21, the summer solstice, and March 14. She also was assigned the fifth hour of the fifth day of the moon.

Obelisk

An obelisk (from Ancient Greek: obeliskos; diminutive of obelos, “spit, nail, pointed pillar”) is a tall, four-sided, narrow tapering monument which ends in a pyramid-like shape or pyramidion at the top. These were originally called tekhenu by their builders, the Ancient Egyptians. The term stele is generally used for other monumental, upright, inscribed and sculpted stones.

Obelisks were prominent in the architecture of the ancient Egyptians, who placed them in pairs at the entrance of temples. The Greeks who saw them used the Greek term ‘obeliskos’ to describe them, and this word passed into Latin and ultimately English. Ancient obelisks are monolithic; that is, they consist of a single stone. Most modern obelisks are made of several stones; some, like the Washington Monument, are buildings.

The word “obelisk” as used in English today is of Greek rather than Egyptian origin because Herodotus, the Greek traveller, was one of the first classical writers to describe the objects. A number of ancient Egyptian obelisks are known to have survived, plus the “Unfinished Obelisk” found partly hewn from its quarry at Aswan. These obelisks are now dispersed around the world, and fewer than half of them remain in Egypt.

The obelisk symbolized the sun god Ra, and during the brief religious reformation of Akhenaten was said to be a petrified ray of the Aten, the sundisk. It was also thought that the god existed within the structure.

Benben was the mound that arose from the primordial waters Nu upon which the creator god Atum settled in the creation story of the Heliopolitan creation myth form of Ancient Egyptian religion. The Benben stone (also known as a pyramidion) is the top stone of the Egyptian pyramid. It is also related to the Obelisk.

It is hypothesized by New York University Egyptologist Patricia Blackwell Gary and Astronomy senior editor Richard Talcott that the shapes of the ancient Egyptian pyramid and obelisk were derived from natural phenomena associated with the sun (the sun-god Ra being the Egyptians’ greatest deity).

The pyramid and obelisk might have been inspired by previously overlooked astronomical phenomena connected with sunrise and sunset: the zodiacal light and sun pillars respectively.

The Ancient Romans were strongly influenced by the obelisk form, to the extent that there are now more than twice as many obelisks standing in Rome as remain in Egypt. All fell after the Roman period except for the Vatican obelisk and were re-erected in different locations.

Dingir / An (“sky”)

Dingir (usually transliterated DIĜIR) is a Sumerian word for “god.” Its cuneiform sign originated as a star-shaped ideogram indicating a god in general, or the Sumerian god An, the supreme father of the gods. It also meant sky or heaven in contrast with ki which meant earth.

Its emesal pronunciation, possibly to be interpreted as “fine tongue” or “high-pitched voice” was dimer. The Sumerian sign is most commonly employed as the determinative for religious names and related concepts, in which case it is not pronounced and is conventionally transliterated as a superscript “D” as in e.g. DInanna.

The cuneiform sign by itself was originally an ideogram for the Sumerian word an (“sky” or “heaven”); its use was then extended to a logogram for the word diĝir (“god” or goddess) and the supreme deity of the Sumerian pantheon An, and a phonogram for the syllable /an/.

Akkadian took over all these uses and added to them a logographic reading for the native ilum and from that a syllabic reading of /il/. In Hittite orthography, the syllabic value of the sign was again only an.

The concept of “divinity” in Sumerian is closely associated with the heavens, as is evident from the fact that the cuneiform sign doubles as the ideogram for “sky”, and that its original shape is the picture of a star. The original association of “divinity” is thus with “bright” or “shining” hierophanies in the sky.

Tian

Tiān is one of the oldest Chinese terms for heaven and a key concept in Chinese mythology, philosophy, and religion. During the Shang Dynasty (17–11th centuries BCE), the Chinese referred to their supreme god as Shàngdì (“Lord on High”) or Dì (“Lord”). During the following Zhou Dynasty, Tiān became synonymous with this figure. Heaven worship was, before the 20th century, an orthodox state religion of China.

In Taoism and Confucianism, Tiān (the celestial aspect of the cosmos, often translated as “Heaven”) is mentioned in relationship to its complementary aspect of Dì ( often translated as “Earth”). These two aspects of Daoist cosmology are representative of the dualistic nature of Taoism.

Taweret

In Ancient Egyptian religion, Taweret (also spelled Taurt, Tuat, Taouris, Tuart, Ta-weret, Tawaret, Twert, Thoeris and Taueret, and in Greek, Θουέρις – Thouéris and Toeris) is the protective ancient Egyptian goddess of childbirth and fertility. The name “Taweret” (Tȝ-wrt) means “she who is great” or simply “great one”, a common pacificatory address to dangerous deities.

Shamash / Tiwas

Utu, later worshipped by East Semitic peoples as Shamash, is the ancient Mesopotamian god of the sun, justice, morality, and truth, and the twin brother of the goddess Inanna, the Queen of Heaven. His main temples were in the cities of Sippar and Larsa. He was believed to ride through the heavens in his sun chariot and see all things that happened in the day. He was the enforcer of divine justice and was thought to aid those in distress.

Tiwaz (Stem: Tiwad-) was the Luwian Sun-god. He was among the most important gods of the Luwians. The name of the Proto-Anatolian Sun god can be reconstructed as *Diuod-, which derives from the Proto-Indo-European word *dei- (“shine”, “glow”). This name is cognate with the Greek Zeus, Latin Jupiter, and Norse Tyr (Old Norse), Tíw (Old English), and Ziu (Old High German) is a god.

Like Latin Jupiter and Greek Zeus, Proto-Germanic *Tīwaz ultimately stems from the Proto-Indo-European theonym *Dyeus. Outside of its application as a theonym, the Old Norse common noun týr means ‘(a) god’ (plural tívar). In turn, the theonym Týr may be understood to mean “the god”.

The t-rune ᛏ is named after Týr, and was identified with this god. The reconstructed Proto-Germanic name is *Tîwaz or *Teiwaz, a letter of the runic alphabet corresponding to the Latin letter T. By way of the process of interpretatio germanica, the deity is the namesake of Tuesday (‘Týr’s day’) in Germanic languages, including English.

Interpretatio romana, in which Romans interpret other gods as forms of their own, generally renders the god as Mars, the ancient Roman war god, and it is through that lens that most Latin references to the god occur.

For example, the god may be referenced as Mars Thingsus (Latin ‘Mars of the Thing’) on 3rd century Latin inscription, reflecting a strong association with the Germanic thing, a legislative body among the ancient Germanic peoples still in use among some of its modern descendants.

In Luwian cuneiform of the Bronze Age, his name appears as Tiwad-. It can also be written with the Sumerogram dUTU (“God-Sun”). In Hieroglyphic Luwian of the Iron Age, the name can be written as Tiwad- of with the ideogram (DEUS) SOL (“God-Sun”).

Tiwaz was the descendant of the male Sun god of the Indo-European religion, Dyeus, who was superseded among the Hittites by the Hattian Sun goddess of Arinna.

In Bronze Age texts, Tiwaz is often referred to as “Father” (cuneiform Luwian: tatis Tiwaz, lithuanian tėvas, ‘father’) and once as “Great Tiwaz” (cuneiform Luwian: urazza- dUTU-az), and invoked along with the “Father gods” (cuneiform Luwian: tatinzi maššaninzi).

His Bronze Age epithet, “Tiwaz of the Oath” (cuneiform Luwian: ḫirutalla- dUTU-az), indicates that he was an oath-god. In this role he received sacrifices of sheep, red meat and bread. The Luwian verb tiwadani- (“to curse”) is derived from Tiwaz’s name.

While Tiwaz (and the related Palaic god Tiyaz) retained a promenant role in the pantheon, the Hittite cognate deity, Šiwat was largely eclipsed by the Sun goddess of Arinna, becoming a god of the day, especially the day of death.

The Sun goddess of Arinna is the chief goddess and wife of the weather god Tarḫunna in Hittite mythology. She protected the Hittite kingdom and was called the “Queen of all lands.” Her cult centre was the sacred city of Arinna.

During the Hittite New Kingdom, she was identified with the Hurrian-Syrian goddess Ḫepat, the mother goddess of the Hurrians, known as “the mother of all living” and a “Queen of the deities”. The mother goddess is likely to have had a later counterpart in the Phrygian goddess Cybele.

Ḫannaḫanna (from Hittite ḫanna- “grandmother”) is a Hurrian Mother Goddess related to or influenced by the Sumerian goddess Inanna. Ḫannaḫanna was also identified with the Hurrian goddess Hebat.

Inara, in Hittite–Hurrian mythology, was the goddess of the wild animals of the steppe and daughter of the Storm-god Teshub/Tarhunt. She corresponds to the “potnia theron” of Greek mythology, better known as Artemis. Inara’s mother is probably Hebat (Artimes) and her brother is Sarruma (Dionysus / Apollo).

In addition to the Sun goddess of Arinna, the Hittites also worshipped the Sun goddess of the Earth and the Sun god of Heaven, while the Luwians originally worshipped the old Proto-Indo-European Sun god Tiwaz.

In the Hittite and Hurrian religions the Sun goddess of the Earth played an important role in the death cult and was understood to be the ruler of the world of the dead. For the Luwians there is a Bronze Age source which refers to the “Sun god of the Earth”: “If he is alive, may Tiwaz release him, if he is dead, may the Sun god of the Earth release him”.

The Sun god of Heaven (Hittite: nepišaš Ištanu) was a Hittite solar deity. He was the second-most worshipped solar deity of the Hittites, after the Sun goddess of Arinna. The Sun god of Heaven was identified with the Hurrian solar deity, Šimige.

From the time of Tudḫaliya III, the Sun god of Heaven was the protector of the Hittite king, indicated by a winged solar disc on the royal seals, and was the god of the kingdom par excellence. From the time of Suppiluliuma I (and probably earlier), the Sun god of Heaven played an important role as the foremost oath god in interstate treaties. As a result of the influence of the Mesopotamian Sun god Šamaš, the Sun god of Heaven also gained an important role as the god of law, legality, and truth.

The Sun goddess of the Earth was the Hittite goddess of the underworld. Her Hurrian equivalent was Allani and her Sumerian/Akkadian equivalent was Ereshkigal, both of which had a marked influence on the Hittite goddess from an early date. In the Neo-Hittite period, the Hattian underworld god, Lelwani was also syncretised with her.

In Hittite texts she is referred to as the “Queen of the Underworld” and possesses a palace with a vizier and servants. As a personification of the chthonic aspects of the Sun she had the task of opening the doors to the Underworld. She was also the source of all evil, impurity, and sickness on Earth. Otherwise she is mostly attested in curses, oaths, and purification rituals.

Taw

Taw, tav, or taf is the twenty-second and last letter of the Semitic abjads. Its original sound value is /t/. It represents either /t/ (voiceless alveolar plosive) or between a /t/ and /d/ sound. It gave rise to the Greek tau (Τ), Latin T, and Cyrillic Т.

The early pictograph evolved into in the Middle Semitic script and continued to evolve into in the Late Semitic Script. From the middle Semitic script is derived the Modern Hebrew ת) . The Early Semitic script is the origin of the Greek and the Latin T.

The mark

The Ancient picture is a type of “mark,” probably of two sticks crossed to mark a place, similar to the Egyptian hieroglyph, a picture of two crossed sticks. This letter has the meanings of “mark,” “sign” and “signature.” The Modern Hebrew, Arabic and Greek names for this letter is tav (or taw), a Hebrew word meaning, “mark.” Hebrew, Greek and Arabic agree that the sound for this letter is “t.

Taw is believed to be derived from the Egyptian hieroglyph meaning “mark”. In Biblical times, the taw was put on men to distinguish those who lamented sin, although newer versions of the Bible have replaced the ancient term taw with mark (Ezekiel 9:4) or signature (Job 31:35).

Ezekiel 9:4 depicts a vision in which the tav plays a Passover role similar to the blood on the lintel and doorposts of a Hebrew home in Egypt. In Ezekiel’s vision, the Lord has his angels separate the demographic wheat from the chaff by going through Jerusalem, the capital city of ancient Israel, and inscribing a mark, a tav, “upon the foreheads of the men that sigh and that cry for all the abominations that be done in the midst thereof.”

In Ezekiel’s vision, then, the Lord is counting tav-marked Israelites as worthwhile to spare, but counts the people worthy of annihilation who lack the tav and the critical attitude it signifies. In other words, looking askance at a culture marked by dire moral decline is a kind of shibboleth for loyalty and zeal for God.

From aleph to tav / omega

Sayings with taf “From aleph to taf” describes something from beginning to end, the Hebrew equivalent of the English “From A to Z.” Omega is the 24th and last letter of the Greek alphabet. As the last letter of the Greek alphabet, Omega is often used to denote the last, the end, or the ultimate limit of a set, in contrast to alpha, the first letter of the Greek alphabet.

In the Greek numeric system/Isopsephy(Gematria) omega has a value of 800. The word literally means “great O” (ō mega, mega meaning “great”), as opposed to omicron, which means “little O” (o mikron, micron meaning “little”).

Omega / Odal rune

In addition to the Greek alphabet, Omega was also adopted into the early Cyrillic alphabet. A Raetic variant is conjectured to be at the origin or parallel evolution of the Elder Futhark ᛟ, the Odal rune, also known as the Othala rune, which represents the o sound. The corresponding Gothic letter is 𐍉 (derived from Greek Ω), which had the name oþal.

The reconstructed Proto-Germanic name of the Odal rune is *ōþalan, meaning “heritage; inheritance, inherited estate”. The Common Germanic stem ōþala- or ōþila- “inherited estate” is an ablaut variant of the stem aþal-. It consists of a root aþ- and a suffix -ila- or -ala-. The suffix variant accounts for the umlauted form ēþel.

Germanic aþal‑ had a meaning of (approximately) “nobility”, and the derivation aþala‑ could express “lineage, (noble) race, descent, kind”, and thus “nobleman, prince” (whence Old English atheling), but also “inheritance, inherited estate, property, possession”. Its etymology is not clear, but it is usually compared to atta “father” (cf. the name Attila, ultimately baby talk for “father”).

There is an apparent, but debated, etymological connection of Odal to Adel (Old High German adal or edil), meaning nobility, noble family line, or exclusive group of superior social status; aristocracy, typically associated with major land holdings and fortifications.

Tav / Truth

Tav is the last letter of the Hebrew word emet, which means ‘truth’. The midrash explains that emet is made up of the first, middle, and last letters of the Hebrew alphabet (aleph, mem, and tav: אמת). Sheqer (falsehood), on the other hand, is made up of the 19th, 20th, and 21st (and penultimate) letters.

Thus, truth is all-encompassing, while falsehood is narrow and deceiving. In Jewish mythology it was the word emet that was carved into the head of the golem which ultimately gave it life. But when the letter aleph was erased from the golem’s forehead, what was left was “met”—dead. And so the golem died.

In gematria, tav represents the number 400, the largest single number that can be represented without using the sophit (final) forms (see kaph, mem, nun, pe, and tzade).

Sade

Ṣade (also spelled Ṣādē, Tsade, Ṣaddi, Ṣad, Tzadi, Sadhe, Tzaddik) is the eighteenth letter of the Semitic abjads, including Phoenician Ṣādē. Its oldest sound value is probably /sˤ/, although there is a variety of pronunciation in different modern Semitic languages and their dialects.

In gematria, Ṣadi represents the number 90. Its final form represents 900, but this is rarely used, Taw, Taw, and Qof (400+400+100) being used instead. As an abbreviation, it stands for ṣafon, North.

It represents the coalescence of three Proto-Semitic “emphatic consonants” in Canaanite. Arabic, which kept the phonemes separate, introduced variants of ṣād and ṭāʾ to express the three (see ḍād, ẓāʾ). In Aramaic, these emphatic consonants coalesced instead with ʿayin and ṭēt, respectively, thus Hebrew ereṣ (earth) is araʿ in Aramaic.

The Phoenician letter is continued in the Greek San (Ϻ) and possibly Sampi, and in Etruscan 𐌑 Ś. It may have inspired the form of the letter Tse in the Glagolitic and Cyrillic alphabet. The corresponding letter of the Ugaritic alphabet is ṣade.

The letter is named “tsadek” in Yiddish, and Hebrew speakers often give it that name as well. This name for the letter probably originated from a fast recitation of the alphabet (i.e., “tsadi, qoph” → “tsadiq, qoph”), influenced by the Hebrew word tzadik, meaning “righteous person”.

The origin of ṣade is unclear. It may have come from a Proto-Sinaitic script based on a pictogram of a plant, perhaps a papyrus plant, or a fish hook (in Modern Hebrew tsad means “[he] hunt[ed]” and in Arabic ṣād means “[he] hunted”).

The root of the word ṣadiq, is ṣ-d-q (tsedek), which means “justice” or “righteousness”. Tzadik is also the root of the word tzedakah (‘charity’, literally ‘righteousness’).

Tzadik ((Hebrew: “righteous [one]”, also zadik, ṣaddîq or sadiq) is a title in Judaism given to people considered righteous, such as Biblical figures and later spiritual masters. Ṣedeq in ancient Canaanite religion may have been an epithet of a god of the Jebusites. The Hebrew word appears in the biblical names Melchizedek, Adonizedek, and Zadok, the high priest of David.

In representing names from foreign languages, a geresh or chupchik can also be placed after the tav, making it represent /θ/, the voiceless dental non-sibilant fricative, a type of consonantal sound used in some spoken languages familiar to English speakers as the ‘th’ in thing.

The voiceless dental non-sibilant fricative is encountered in some of the most widespread and influential languages. The symbol that represents this sound is ⟨θ⟩, and the equivalent X-SAMPA symbol is T. The IPA symbol is the Greek letter theta, which is used for this sound in post-classical Greek, and the sound is thus often referred to as “theta”.

Theth – Theta

Teth, also written as Ṭēth or Tet, is the ninth letter of the Semitic abjads, including Phoenician Ṭēt. It is 16th in modern Arabic order. The Persian ṭa is pronounced as a hard “t” sound and is the 19th letter in the modern Persian alphabet.

The Phoenician letter name ṭēth means “wheel”, but the letter possibly (according to Brian Colless) continues a Middle Bronze Age glyph named ṭab “good” based on the nfr “good” hieroglyph.

Jewish scripture books about the “holy letters” from the 10th century and on discuss the connection or origin of the letter Teth with the word Tov, and the Bible uses the word ‘Tov’ in alphabetic chapters to depict the letter.

In gematria, Tet represents the number nine. When followed by an apostrophe, it means 9,000. As well, in gematria, the number 15 is written with Tet and Vav, (9+6) to avoid the normal construction Yud and Hei (10+5) which spells a name of God. Similarly, 16 is written with Tet and Zayin (9+7) instead of Yud and Vav (10+6) to avoid spelling part of the Tetragrammaton.

The Phoenician letter also gave rise to the Greek theta (uppercase Θ or ϴ, lowercase θ which resembles digit 0 with horizontal line), the eighth letter of the Greek alphabet, originally an aspirated voiceless alveolar stop but now used for the voiceless dental fricative. In the system of Greek numerals it has the value 9.

In the Latin script used for the Gaulish language, theta developed into the tau gallicum, conventionally transliterated as Ð (eth), although the bar extends across the centre of the letter. The phonetic value of the tau gallicum is thought to have been [t͡s].

In ancient times, tau was used as a symbol for life or resurrection, whereas the eighth letter of the Greek alphabet, theta, was considered the symbol of death. According to Porphyry of Tyros, the Egyptians used an X within a circle as a symbol of the soul; having a value of nine, it was used as a symbol for Ennead.

Johannes Lydus says that the Egyptians used a symbol for Kosmos in the form of theta, with a fiery circle representing the world, and a snake spanning the middle representing Agathos Daimon (literally: good spirit).

Thanatos

In classical Athens Theta was used as an abbreviation for the Greek thanatos (“death”) and as it vaguely resembles a human skull, theta was used as a warning symbol of death, in the same way that skull and crossbones are used in modern times. It survives on potsherds used by Athenians when voting for the death penalty.

Petrus de Dacia in a document from 1291 relates the idea that theta was used to brand criminals as empty ciphers, and the branding rod was affixed to the crossbar spanning the circle. For this reason, use of the number theta was sometimes avoided where the connotation was felt to be unlucky—the mint marks of some Late Imperial Roman coins famously have the sum ΔΕ or ΕΔ (delta and epsilon, that is 4 and 5) substituted as a euphemism where a Θ (9) would otherwise be expected.

In Greek mythology, Thanatos (“Death” from “to die, be dying”) was the personification of death. He was a minor figure in Greek mythology, often referred to but rarely appearing in person. The Greek poet Hesiod established in his Theogony that Thánatos is a son of Nyx (Night) and Erebos (Darkness) and twin of Hypnos (Sleep).

His name is transliterated in Latin as Thanatus, but his equivalent in Roman mythology is Mors or Letum. Mors is sometimes erroneously identified with Orcus, whose Greek equivalent was Horkos, God of the Oath.

In Greek mythology, the figure of Horkos (“oath”) personifies the curse that will be inflicted on any person who swears a false oath. Oath-taking and the penalties for perjuring oneself played an important part in the Ancient Greek concept of justice.

Hesiod’s Theogony identifies Horkos as the son of Eris (“strife”) and brother of various tribulations: Ponos (“Hardship”), Lethe (“Forgetfulness”), Limos (“Starvation”), Algae (“Pains”), Hysminai (“Battles”), Makhai (“Wars”), Phonoi (“Murders”), Androktasiai (Manslaughters”), Neikea (“Quarrels”), Pseudea (“Lies”), Logoi (“Stories”), Amphillogiai (“Disputes”), Dysnomia (“Anarchy”), and Ate (“Ruin”).

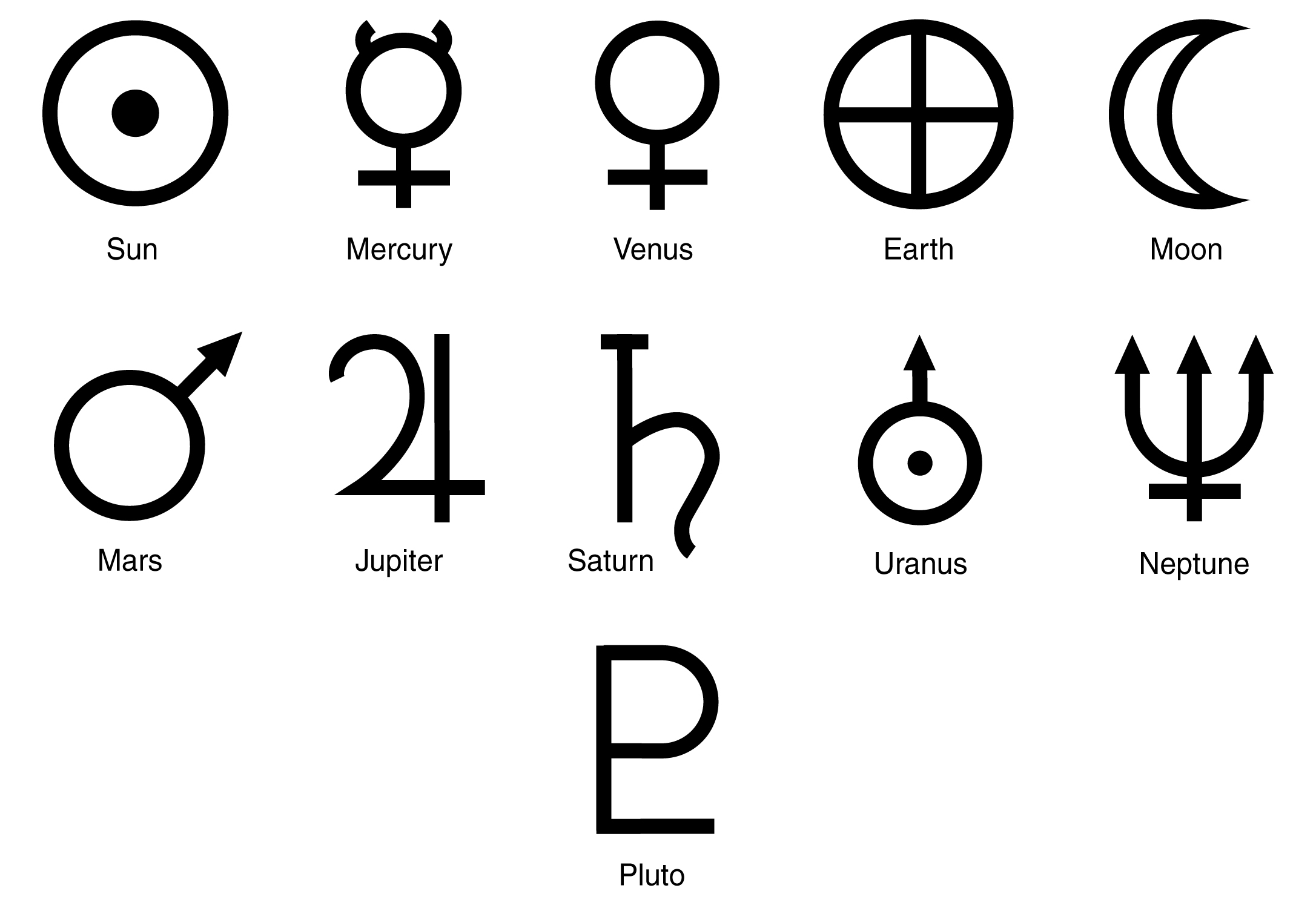

Point / Cross within the circle

In its archaic form theta was written as a cross within a circle (as in the Etruscan A symbol of a cross within a circle or another symbol of a cross within a circle), and later, as a line or point in circle (The symbol of a line within a circle or The symbol of a point within a circle).

Egyptian hieroglyphs have a large inventory of solar symbolism because of the central position of solar deities (Ra, Horus, Aten etc.) in Ancient Egyptian religion. The main ideogram for “Sun” was a representation of the solar disk, with a variant including the Uraeus.

The Egyptians used the symbol of a point within a circle (The symbol of a point within a circle, the sun disc) to represent the sun, which might be a possible origin of its use as the Sun’s astrological glyph. It is worthwhile to note that theta has the same numerical value in isopsephy as Helios.

The emblem is a very old one, a solar-phallic symbol used in ancient Egypt to represent the eternal nature of the sun god Ra. The lines which enclose the circle call to mind the akhet, the ancient ‘gate’ of the sun, a symol of rebirth and resurrection. It is associated with St. John the Baptist and St. John the Evangelist, whose feast days fall on the summer and winter solstices.

To the Pythagoreans, the point and circle represented eternity, whose “centre is everywhere and the circumference nowhere.” The point and the circle can be expressed as the same substance as potential (the point or monad) and as fully manifest (the circle.)

The “Sun” ideogram in early Chinese writing, beginning with the oracle bone script (c. 12th century BC) also shows the solar disk with a central dot (whence the modern character 日), analogous to the Egyptian heroglyph.

A sun cross, solar cross, or wheel cross is a solar symbol consisting of an equilateral cross inside a circle. The “sun cross” or “solar wheel” (🜨) is often considered to represent the four seasons and the tropical year, and therefore the Sun. The same symbol is in use as a modern astronomical symbol representing the Earth rather than the Sun.

The design is frequently found in the symbolism of prehistoric cultures, particularly during the Neolithic to Bronze Age periods of European prehistory. The symbol’s ubiquity and apparent importance in prehistoric religion have given rise to its interpretation as a solar symbol, whence the modern English term “sun cross” (a calque of German: Sonnenkreuz).

The Bronze Age symbol has also been connected with the spoked chariot wheel, which at the time was four-spoked (compare the Linear B ideogram “wheel”). In the context of a culture that celebrated the Sun chariot, it may thus have had a “solar” connotation (c.f. the Trundholm sun chariot).

In the prehistoric religion of Bronze Age Europe, crosses in circles appear frequently on artifacts identified as cult items, for example the “miniature standard” with an amber inlay that shows a cross shape when held against the light, dating to the Nordic Bronze Age, held at the National Museum of Denmark, Copenhagen.

The interpretation of the simple equilateral cross as a solar symbol in Bronze Age religion was widespread in 19th-century scholarship. The cross-in-a-circle was interpreted as a solar symbol derived from the interpretation of the disc of the Sun as the wheel of the chariot of the Sun god.

It has been postulated that the Gothic rune hvel (“wheel”) represents the solar deity by the “wheel” symbol of a cross-in-a-circle, reflected by the Gothic letter hwair (𐍈) (also ƕair, huuair, hvair), the name of the Gothic letter expressing the [hʷ] or [ʍ] sound (reflected in English by the inverted wh-spelling for [ʍ]).

Popular legend in Ireland says that the Celtic Christian cross was introduced by Saint Patrick or possibly Saint Declan, though there are no examples from this early period.

It has often been claimed that Patrick combined the symbol of Christianity with the sun cross to give pagan followers an idea of the importance of the cross. By linking it with the idea of the life-giving properties of the sun, these two ideas were linked to appeal to pagans. Other interpretations claim that placing the cross on top of the circle represents Christ’s supremacy over the pagan sun.

The vertical bar represents North and South while the horizontal bar is East and West. There is a 31 degree saltire that is also associated with this symbol. When laid over the cross it represents the solstices and equinoxes with precision.

This configuration is an ideogram reflected through many cultures and extends far back into antiquity. Henges are a testament that there was an ancient understanding of the Sun’s behavior in the sky and that it was measurable, predictable and center to their continued existence on Earth. The original Coptic cross often includes a circle that is derived from the ankh, as the circles represent the sun god, Ra. Early Gnostic sects also used a circle cross.

In the prehistoric religion of Bronze Age Europe, crosses in circles appear frequently on artifacts identified as cult items, for example the “miniature standard” with an amber inlay that shows a cross shape when held against the light, dating to the Nordic Bronze Age, held at the National Museum of Denmark, Copenhagen.

The Bronze Age symbol has also been connected with the spoked chariot wheel, which at the time was four-spoked (compare the Linear B ideogram “wheel”). In the context of a culture that celebrated the sun chariot, it may thus have had a “solar” connotation (compare the Trundholm sun chariot).

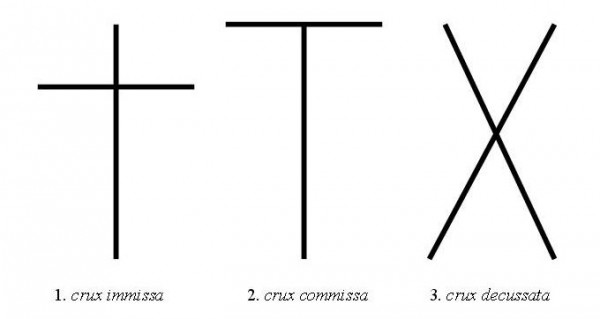

Tau cross

Tau is the 19th letter of the Greek alphabet. In the system of Greek numerals it has a value of 300. The symbolism of the cross was connected not only to the letter chi but also to tau. The tau cross is a T-shaped cross all three ends of which are sometimes expanded. It is so called because shaped like the Greek letter tau, which in its upper-case form has the same appearance as Latin and English T.

Another name for the same object is Saint Anthony’s cross or Saint Anthony cross, a name given to it because of its association with Saint Anthony of Egypt. It is also called a crux commissa, one of the four basic types of iconographic representations of the cross.

The Epistle of Barnabas (late first century or early second) gives an allegorical interpretation of the number 318 (in Greek numerals τιη’) in the text of Book of Genesis 14:14 as intimating the crucifixion of Jesus by viewing the numerals ιη’ (18) as the initial letters of Iēsus, and the numeral τ’ (300) as a prefiguration of the cross:

“What, then, was the knowledge given to him in this? Learn the eighteen first, and then the three hundred. The ten and the eight are thus denoted—Ten by Ι, and Eight by Η. You have [the initials of the name of] Jesus. And because the cross was to express the grace [of our redemption] by the letter Τ, he says also, ‘Three Hundred’. He signifies, therefore, Jesus by two letters, and the cross by one.”

Clement of Alexandria (c. 150 – c. 215) gives the same interpretation of the number τιη’ (318), referring to the cross of Christ with the expression “the Lord’s sign”: “They say, then, that the character representing 300 is, as to shape, the type of the Lord’s sign, and that the Iota and the Eta indicate the Saviour’s name.”

Tertullian (c. 155 – c. 240) remarks that the Greek letter τ and the Latin letter T have the same shape as the execution cross: “Ipsa est enim littera Graecorum Tau, nostra autem T, species crucis”.

In the Trial of the Court of the Vowels of non-Christian Lucian (125 – after 180), the Greek letter Sigma (Σ) accuses the letter Tau (Τ) of having provided tyrants with the model for the wooden instrument with which to crucify people and demands that Tau be executed on his own shape:

“It was his body that tyrants took for a model, his shape that they imitated, when they set up the erections on which men are crucified. Σταυρός the vile engine is called, and it derives its vile name from him. Now, with all these crimes upon him, does he not deserve death, nay, many deaths? For my part I know none bad enough but that supplied by his own shape—that shape which he gave to the gibbet named σταυρός after him by men”.

Stauros

Stauros (σταυρός) is a Greek word, which in the oldest forms (Homeric and classical) of that language (until the fourth century B.C.) is found used in the plural number in the sense of an upright stake or pole; in Koine Greek, in use during the Hellenistic and Roman periods, within which the New Testament was written, it was used in the singular number with reference to an instrument of capital punishment; in modern Greek it is used to refer only to a cross, real or metaphorical.

The word stauros comes from the verb meaning to “straighten up”, “stand”), which in turn comes from the Proto-Indo-European root *steh-u- “pole”, related to the root *steh- “to stand, to set” (the same root is found in German Stern, or Stamm, the English “stand”, the Spanish word estaca, the Portuguese word estaca, the Polish stać, the Italian stare, of similar meanings).

In Homeric and classical Greek, until the early 4th century BC, stauros meant an upright stake, pole, or piece of paling, “on which anything might be hung, or which might be used in impaling [fencing in] a piece of ground.” In the literature of that time, it never means two pieces of timber placed across one another at any angle, but always one piece alone, and is always used in the plural number, never in the singular.

In Koine Greek, the form of Greek in use between about 300 BC and AD 300, the word was used to denote a wooden object on which Romans executed criminals. When the word is thus employed in the writings of the Diodorus Siculus (1st century BC), Plutarch and Lucian – non-Christian writers, of whom only Lucian makes clear the shape of the device – the authoritative A Greek–English Lexicon translates it as “cross”.

According to the Encyclopædia Britannica, this form of capital punishment involved binding the victim with outstretched arms to a crossbeam, or nailing him firmly to it through the wrists; the crossbeam was then raised against an upright shaft and made fast to it about 3 metres from the ground, and the feet were tightly bound or nailed to the upright shaft.

Speaking specifically about the σταυρός of Jesus, early Christian writers unanimously suppose it to have had a crossbeam. Thus Justin Martyr said it was prefigured in the Jewish Passover lamb: “That lamb which was commanded to be wholly roasted was a symbol of the suffering of the cross (σταυρός) which Christ would undergo.

For the lamb, which is roasted, is roasted and dressed up in the form of the cross (σταυρός). For one spit is transfixed right through from the lower parts up to the head, and one across the back, to which are attached the legs of the lamb.”

In A Critical Lexicon and Concordance to The English and Greek New Testament (1877), hyperdispensationalist E. W. Bullinger, in contrast to other authorities, stated: “The σταυρός was simply an upright pale or stake to which Romans nailed those who were thus said to be crucified, σταυρόω, merely means to drive stakes. It never means two pieces of wood joining at any angle. Even the Latin word crux means a mere stake.

The initial letter Χ, (chi) of Χριστός, (Christ) was anciently used for His name, until it was displaced by the T, the initial letter of the pagan god Tammuz, about the end of cent. iv.” A similar view was put forward by John Denham Parsons in 1896.

Bullinger’s 1877 statement and that of Parsons in 1896, written before the discovery of thousands of manuscripts in Koine Greek at Oxyrhyncus in Egypt revolutionised understanding of the language of the New Testament, conflict with the documented fact that, long before the end of the fourth century, the Epistle of Barnabas, which was certainly earlier than 135, and may have been of the 1st century AD, the time when the gospel accounts of the death of Jesus were written, likened the σταυρός to the letter T (the Greek letter tau, which had the numeric value of 300), and to the position assumed by Moses in Exodus 17:11-12.

The shape of the σταυρός is likened to that of the letter T also in the final words of Trial in the Court of Vowels among the works of 2nd-century Lucian, and other 2nd-century witnesses to the fact that at that time the σταυρός was envisaged as being cross-shaped and not in the form of a simple pole are given in early Christian descriptions of the execution cross.

The Greek word σταυρός, which in the New Testament refers to the structure on which Jesus died, appears as early as AD 200 in two papyri, Papyrus 66 and Papyrus 75 in a form that includes the use of a cross-like combination of the letters tau and rho. This tau-rho symbol, the staurogram, appears also in Papyrus 45 (dated 250), again in relation to the crucifixion of Jesus.

The Early Christians probably saw in the staurogram a depiction of Jesus on the cross, with the cross represented (as elsewhere) by the tau and the head by the loop of the rho. The staurogram constitutes a Christian artistic emphasis on the cross within the earliest textual tradition.

Sigma

Sigma (uppercase Σ, lowercase σ) is the eighteenth letter of the Greek alphabet. In the system of Greek numerals, it has a value of 200. The shape and alphabetic position of sigma is derived from Phoenician shin 𐤔.

The name of sigma, according to one hypothesis, may continue that of Phoenician Samekh. To express an etymological /ś/, a number of dialects chose either sin or samek exclusively, where other dialects switch freely between them (often ‘leaning’ more often towards one or the other).

Samekh or Simketh is the fifteenth letter of many Semitic abjads, representing /s/. The Arabic alphabet, however, uses a letter based on Phoenician Šīn to represent /s/; however, that glyph takes Samekh’s place in the traditional Abjadi order of the Arabic alphabet.

The Phoenician letter gave rise to the Greek Xi (Ξ, ξ), the 14th letter of the Greek alphabet. However, its name gave rise to Sigma. In the system of Greek numerals the letter Xi has a value of 60. It is not to be confused with the letter chi, which gave its form to the Latin letter X.

Samekh in gematria has the value 60. Samekh and Mem can be combined to form the abbreviation ס”ם, known as samekh-mem, a euphemism used for the name of the angel Samael to avoid speaking his name aloud and thereby attracting his attention.

In Judaism, Samael (Hebrew: “Venom of God,” “Poison of God,” or “Blindness of God”) is an important archangel in Talmudic and post-Talmudic lore, a figure who is the accuser (Ha-Satan), seducer, and destroyer (Mashhit), and has been regarded as both good and evil.

He is said to be the angel of death, and the title “Satan” is accorded to him. While Satan describes his function as an accuser, Samael is considered to be his proper name. While Michael defends Israel’s actions, Samael tempts people to sin.

He is also depicted as the angel of death and one of the seven archangels, the ruler over the Fifth Heaven and commander of two million angels such as the chief of other Satans. Yalkut Shimoni (I, 110) presents Samael as Esau’s guardian angel.

In some legends, samekh is said to have been a miracle of the Ten Commandments. Exodus 32:15 records that the tablets “were written on both their sides.”

The Jerusalem Talmud interprets this as meaning that the inscription went through the full thickness of the tablets. The stone in the center parts of the letters ayin and teth should have fallen out, as it was not connected to the rest of the tablet, but it miraculously remained in place.

The Babylonian Talmud on the other hand attributes this instead to samekh, but samekh did not have such a hollow form in the sacred Paleo-Hebrew alphabet that would presumably have been used for the tablets. However, this would be appropriate for the Rabbis who maintained that the Torah or the Ten Commandments were given in the later Hebrew “Assyrian” script.

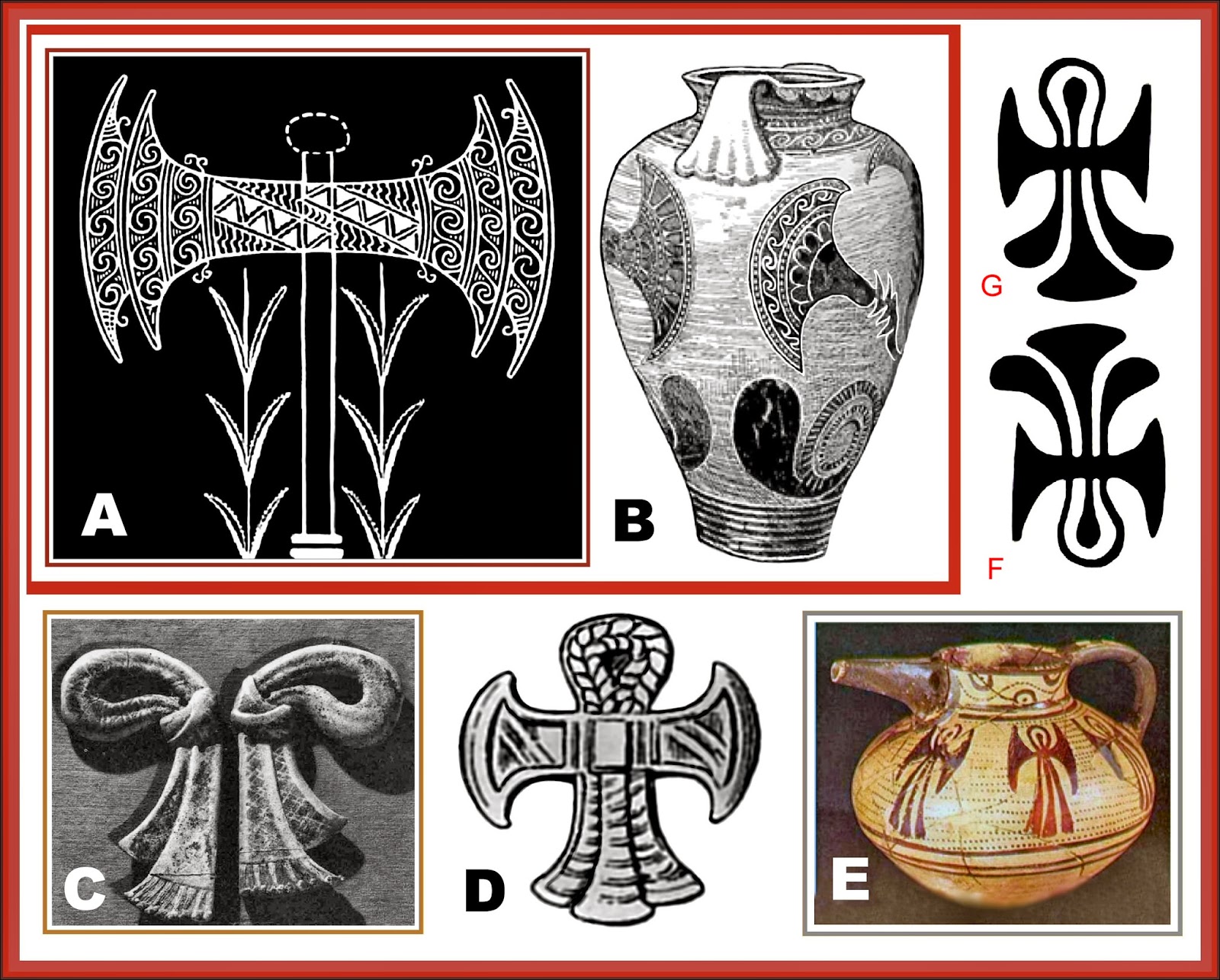

The djed

The origin of Samekh is unclear. The Phoenician letter may continue a glyph from the Middle Bronze Age alphabets, either based on a hieroglyph for a tent peg / some kind of prop (s’mikhah or t’mikhah in modern Hebrew it means to support), and thus may be derived from the Egyptian hieroglyph djed.

The djed (Ancient Egyptian: ḏd, Coptic jōt “pillar”) is one of the more ancient and commonly found symbols in ancient Egyptian religion. It is a pillar-like symbol in Egyptian hieroglyphs representing stability. It is associated with the creator god Ptah and Osiris, the Egyptian god of the afterlife, the underworld, and the dead. It is commonly understood to represent his spine.

The djed may originally have been a fertility cult related pillar made from reeds or sheaves or a totem from which sheaves of grain were suspended or grain was piled around.

It has been speculated that the ankh, djed, and was symbols have a biological basis derived from ancient cattle culture (linked to the Egyptian belief that semen was created in the spine), thus the ankh symbolized life, thoracic vertebra of a bull (seen in cross section), the djed symbolized stability, base on sacrum of a bull’s spine, and the was-sceptre symbolized power and dominion, a staff featuring the head and tail of the god Set, “great of strength”.

The ankh, a symbole of life through sexual union, is like a yoni on top of a lingam, or vesica piscis on top of a tau if you will. The Hindu Ardhanari is a composite androgynous form of the Hindu god Shiva and his consort Parvati (the latter being known as Devi, Shakti and Uma in this icon): half male and half female, split down the middle.

Ardhanarishvara is depicted as half-male and half-female, equally split down the middle. The right half is usually the male Shiva, illustrating his traditional attributes. The Ankh is here used here as a depiction of both male and female genitalia.

The ancient Greek considered Tau to be symbolic oflife and resurrection, while ‘theta’, the 8th letter of the alphabet was used to denote death. In ancient Egypt, the Tau symbol was thought to represent a phallus and was also regarded as the marker for holy waters. Ancient mythology associates the symbol with the Greek deity Attis and the Roman god Mithra or Mithras. Several Western religious traditions and European cultures associate Tau with the crucifix.

We find this image in primitive/native man glyphs as a representation of the meeting place between earth and sky (horizon). Consider the deeper meaning here – that which is above the horizon (or at the table top of the T) is known to our conscious minds. That which is below the point of contact (the stem of the T) holds the mystery of the unknown.

The was (Egyptian wꜣs “power, dominion”) sceptre is a symbol that appeared often in relics, art, and hieroglyphics associated with the ancient Egyptian religion. It appears as a stylized animal head at the top of a long, straight staff with a forked end.

Was sceptres were used as symbols of power or dominion, and were associated with ancient Egyptian deities such as Set or Anubis as well as with the pharaoh. Was sceptres also represent the Set animal. In later use, it was a symbol of control over the force of chaos that Set represented.

In a funerary context the was sceptre was responsible for the well-being of the deceased, and was thus sometimes included in the tomb equipment or in the decoration of the tomb or coffin. The sceptre is also considered an amulet. The Egyptians perceived the sky as being supported on four pillars, which could have the shape of the was. This sceptre was also the symbol of the fourth Upper Egyptian nome, the nome of Thebes (called wꜣst in Egyptian).

Was sceptres were depicted as being carried by gods, pharaohs, and priests. They commonly occur in paintings, drawings, and carvings of gods, and often parallel with emblems such as the ankhand the djed-pillar. Remnants of real was sceptres have been found. They are constructed of faience or wood, where the head and forked tail of the Set-animal are visible. The earliest examples date to the First Dynasty. The Was (wꜣs) is the Egyptian hieroglyph character representing power.

Anyway, the djed came to be associated with Seker, the falcon god of the Memphite Necropolis, then with Ptah, the Memphite patron god of craftsmen. Ptah was often referred to as “the noble djed”, and carried a scepter that was a combination of the djed symbol and the ankh, the symbol of life. Ptah gradually came to be assimilated into Osiris. By the time of the New Kingdom, the djed was firmly associated with Osiris.

The djed hieroglyph was a pillar-like symbol that represented stability. It was also sometimes used to represent Osiris himself, often combined “with a pair of eyes between the crossbars and holding the crook and flail.” It is often found together with the tyet hieroglyph, sometimes called the knot of Isis or girdle of Isis, an ancient Egyptian symbol that came to be connected with the goddess Isis.

The tyet resembles a knot of cloth and may have originally been a bandage used to absorb menstrual blood. In many respects the tyet resembles an ankh, except that its arms curve down. Its meaning is also reminiscent of the ankh, as it is often translated to mean “welfare” or “life”. The djed and the tiet used together may depict the duality of life. The tyet hieroglyph may have become associated with Isis because of its frequent pairing with the djed.

Shin

Shin (also spelled Šin (šīn) or Sheen) is the name of the twenty-first letter of the Semitic abjads, In the Arabic alphabet, šīn is at the original (21st) position in Abjadi order. A letter variant sīn takes the place of Samekh at 15th position.

The Proto-Sinaitic glyph may have been based on a pictogram of a tooth (in modern Hebrew shen) and with the phonemic value š “corresponds etymologically (in part, at least) to original Semitic ṯ (th), which was pronounced s in South Canaanite”. The Encyclopaedia Judaica, 1972, records that it originally represented a composite bow.

The Arabic letter šīn was an acronym for “something”, meaning the unknown in algebraic equations. In the transcription into Spanish, the Greek letter chi (χ) was used which was later transcribed into Latin x. Chi is the 22nd letter of the Greek alphabet, pronounced /kaɪ/ or /kiː/ in English.

In Plato’s Timaeus, it is explained that the two bands that form the soul of the world cross each other like the letter Χ. Chi or X is often used to abbreviate the name Christ, as in the holiday Christmas (Xmas). When fused within a single typespace with the Greek letter Rho, it is called the labarum and used to represent the person of Jesus Christ.

According to some sources, this is the origin of x used for the unknown in the equations. However, according to other sources, there is no historical evidence for this. In Modern Arabic mathematical notation, sīn, i.e. šīn without its dots, often corresponds to Latin x.

In gematria, Shin represents the number 300. Shin, as a prefix, bears the same meaning as the relative pronouns “that”, “which” and “who” in English. In colloquial Hebrew, Kaph and Shin together have the meaning of “when”. This is a contraction of ka’asher (as, when).

According to Judges 12:6, the tribe of Ephraim could not differentiate between Shin and Samekh; when the Gileadites were at war with the Ephraimites, they would ask suspected Ephraimites to say the word shibolet; an Ephraimite would say sibolet and thus be exposed.

From this episode we get the English word shibboleth, signifying any custom or tradition, particularly a speech pattern, that distinguishes one group of people (an ingroup) from others (outgroups). Shibboleths have been used throughout history in many societies as passwords, simple ways of self-identification, signaling loyalty and affinity, maintaining traditional segregation or keeping out perceived threats.

Shin also stands for the word Shaddai, a name for God. Because of this, a kohen (priest) forms the letter Shin with his hands as he recites the Priestly Blessing. It is often inscribed on the case containing a mezuzah, a scroll of parchment with Biblical text written on it.

The text contained in the mezuzah is the Shema Yisrael prayer, which calls the Israelites to love their God with all their heart, soul and strength. The mezuzah is situated upon all the doorframes in a home or establishment. Sometimes the whole word Shaddai will be written.

The Shema Yisrael prayer also commands the Israelites to write God’s commandments on their hearts (Deut. 6:6); the shape of the letter Shin mimics the structure of the human heart: the lower, larger left ventricle (which supplies the full body) and the smaller right ventricle (which supplies the lungs) are positioned like the lines of the letter Shin.

A religious significance has been applied to the fact that there are three valleys that comprise the city of Jerusalem’s geography: the Valley of Ben Hinnom, Tyropoeon Valley, and Kidron Valley, and that these valleys converge to also form the shape of the letter shin, and that the Temple in Jerusalem is located where the dagesh (horizontal line) is.

This is seen as a fulfillment of passages such as Deuteronomy 16:2 that instructs Jews to celebrate the Pasach at “the place the LORD will choose as a dwelling for his Name” (NIV).

In the Sefer Yetzirah the letter Shin is King over Fire, Formed Heaven in the Universe, Hot in the Year, and the Head in the Soul. Sh’at haShin (the Shin hour) is the last possible moment for any action, usually military. Corresponds to the English expression the eleventh hour.

The 13th-century Kabbalistic text Sefer HaTemunah, holds that a single letter of unknown pronunciation, held by some to be the four-pronged shin on one side of the teffilin box, is missing from the current alphabet. The world’s flaws, the book teaches, are related to the absence of this letter, the eventual revelation of which will repair the universe.

Rune sowilo / sun

The Phoenician letter šin from which the Old Italic s letter ancestral to the rune *Sowilō or *sæwelō, the reconstructed Proto-Germanic language name of the s-rune, meaning “sun”, was derived was itself named after the Sun, shamash, based on the Egyptian uraeus hieroglyph. The name is attested for the same rune in all three Rune Poems. It appears as Old Norse sól, Old English sigel, and Gothic sugil.

This continues a Proto-Indo-European alternation *suwen- vs. *sewol- (Avestan xweng vs. Latin sōl, Greek helios, Sanskrit surya, Welsh haul, Breton heol, Old Irish suil “eye”), a remnant of an archaic, so-called “heteroclitic”, declension pattern that remained productive only in the Anatolian languages.