Confusion of tongues

Posted by Sjur Cappelen Papazian on July 27, 2015

Enmerkar and the Lord of Aratta is a legendary Sumerian account, of preserved, early post-Sumerian copies, composed in the Neo-Sumerian period (ca. 21st century BC). It is one of a series of accounts describing the conflicts between Enmerkar, king of Unug-Kulaba (Uruk), and the unnamed king of Aratta (probably somewhere in modern Iran or Armenia).

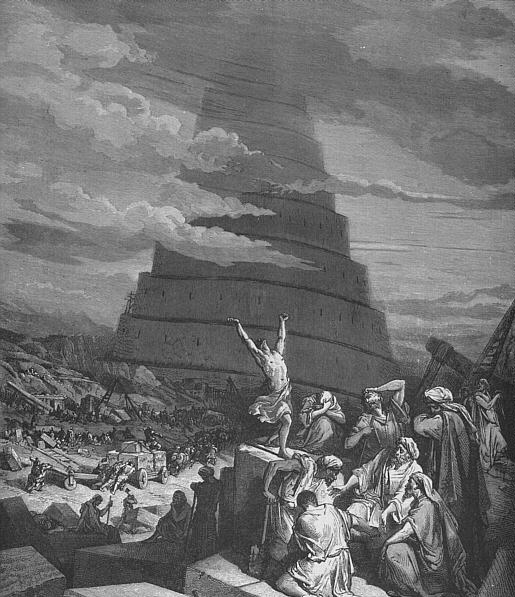

Because it gives a Sumerian account of the “confusion of tongues”, and also involves Enmerkar constructing temples at Eridu and Uruk, it has, since the time of Samuel Kramer, been compared with the Tower of Babel narrative in the Book of Genesis. God dispersed them by confusing their language, and hence the name Babel, meaning “confusion.”

The ziggurat had an important role in the civilizations of southern Mesopotamia from the earliest development of urbanized life to the high political reaches of the Neo-Babylonian Empire. It is common for the ziggurat to be of central importance in city planning. The structure at Eridu, the earliest structure that some designate a ziggurat, is dated in its earliest level to the Ubaid period (4300-3500).

Nearly 30 ziggurats in the area of Mesopotamia have been discovered by archaeologists. In location, they stretch from Mari and Tell-Brak in the northwest and Dur-Sharrukin in the north, to Ur and Eridu in the south, and to Susa and Choga Zambil in the east. In time, the span begins perhaps as early as the Ubaid temples at Eridu (end of the 5th millennium BC) and extends through the restorations and additions made even in Seleucid times (third century BC).

The confusion of tongues (confusio linguarum) is the initial fragmentation of human languages described in the Book of Genesis 11:1–9, as a result of the construction of the Tower of Babel. This event sent by God was the ultimate cause of the early separation of mankind, their dispersal throughout the Earth, and their division into races and nations.

After the Flood, as the human population quickly grew, some descendants of Noah built a tower to prevent their dispersion; but God “confounded their language” (Gen. 11:1-8), and they were scattered over the whole Earth. Up until this time “the whole Earth was of one language and of one speech.”

In the Sumerian epic entitled Enmerkar and the Lord of Aratta, in a speech of Enmerkar, an incantation is pronounced that has a mythical introduction.

Kramer’s translation is as follows:

Once upon a time there was no snake, there was no scorpion,

There was no hyena, there was no lion,

There was no wild dog, no wolf,

There was no fear, no terror,

Man had no rival.

In those days, the lands of Subur (and) Hamazi,

Harmony-tongued Sumer, the great land of the decrees of princeship,

Uri, the land having all that is appropriate,

The land Martu, resting in security,

The whole universe, the people in unison

To Enlil in one tongue [spoke].

(Then) Enki, the lord of abundance (whose) commands are trustworthy,

The lord of wisdom, who understands the land,

The leader of the gods,

Endowed with wisdom, the lord of Eridu

Changed the speech in their mouths, [brought] contention into it,

Into the speech of man that (until then) had been one.

Enmerkar and the Lord of Aratta

The Sumerian mythological epic Enmerkar and the Lord of Aratta lists the countries where the “languages are confused” as Subartu, Hamazi, Sumer, Uri-ki, and the Martu land. Similarly, the earliest references to the “four quarters” by the kings of Akkad name Subartu as one of these quarters around Akkad, along with Martu, Elam, and Sumer. Subartu in the earliest texts seem to have been farming mountain dwellers, frequently raided for slaves.

Babylon

Eridu (Cuneiform: NUN.KI; Sumerian: eridu; Akkadian: irîtu modern Arabic: Tell Abu Shahrain) is an archaeological site in southern Mesopotamia (modern Dhi Qar Governorate, Iraq). It is considered the earliest city in southern Mesopotamia.

In Sumerian mythology, Eridu was originally the home of Enki, later known by the Akkadians as Ea, who was considered to have founded the city. The urban nucleus of Eridu was Enki’s temple, The name refers to Enki’s realm. His consort Ninhursaga had a nearby temple at Ubaid.

His temple was called E-Abzu or House of the Aquifer (Cuneiform: E.ZU.AB; Sumerian: e-abzu; Akkadian: bītu apsû), which in later history was called House of the Waters (Cuneiform: E.LAGAB×HAL; Sumerian: e-engur; Akkadian: bītu engurru), as Enki was believed to live in Abzu, an aquifer from which all life was believed to stem.

Aside from Enmerkar of Uruk (as mentioned in the Aratta epics), several later historical Sumerian kings are said in inscriptions found here to have worked on or renewed the e-abzu temple.

The Egyptologist David Rohl has conjectured that Eridu, to the south of Ur, was the original Babel and site of the Tower of Babel, rather than the later city of Babylon, because the ziggurat ruins of Eridu are far larger and older than any others, and seem to best match the Biblical description of the unfinished Tower of Babel. One name of Eridu in cuneiform logograms was pronounced “NUN.KI” (“the Mighty Place”) in Sumerian, but much later the same “NUN.KI” was understood to mean the city of Babylon.

The much later Greek version of the King-list by Berossus (c. 200 BC) reads “Babylon” in place of “Eridu” in the earlier versions, as the name of the oldest city where “the kingship was lowered from Heaven”.

Rohl further equate Biblical Nimrod, said to have built Erech (Uruk) and Babel, with the name Enmerkar (-KAR meaning “hunter”) of the king-list and other legends, who is said to have built temples both in his capital of Uruk and in Eridu.

Other scholars have discussed at length a number of additional correspondences between the names of “Babylon” and “Eridu”. Historical tablets state that Sargon of Akkad (ca. 2300 BC) dug up the original “Babylon” and rebuilt it near Akkad, though some scholars suspect this may in fact refer to the much later Assyrian king Sargon II.

Subartu

The land of Subartu (Akkadian Šubartum/Subartum/ina Šú-ba-ri, Assyrian mât Šubarri) or Subar (Sumerian Su-bir/Subar/Šubur) is mentioned in Bronze Age literature. The name also appears as Subari in the Amarna letters, and, in the form Šbr, in Ugarit.

Subartu was apparently a polity in Northern Mesopotamia, at the upper Tigris. Some scholars suggest that Subartu is an early name for Assyria proper on the Tigris and westward, although there are various other theories placing it sometimes a little farther to the east and/or north.

Its precise location has not been identified. From the point of view of the Akkadian Empire, Subartu marked the northern geographical horizon, just as Martu, Elam and Sumer marked “west”, “east” and “south”, respectively.

Eannatum of Lagash was said to have smitten Subartu or Shubur, and it was listed as a province of the empire of Lugal-Anne-Mundu; in a later era Sargon of Akkad campaigned against Subar, and his grandson Naram-Sin listed Subar along with Armani, an ancient kingdom mentioned by Sargon of Akkad and his grandson Naram-Sin of Akkad as stretching from Ibla to Bit-Nanib, and is continued to be mentioned in the later Assyrian inscriptions, which has been identified with Aleppo, among the lands under his control. Ishbi-Erra of Isin and Hammurabi also claimed victories over Subar.

Subartu may have been in the general sphere of influence of the Hurrians. There are various alternate theories associating the ancient Subartu with one or more modern cultures found in the region, including Armenian or Kurdish tribes.

Shupria (Shubria) or Arme-Shupria (Akkadian: Armani-Subartu from the 3rd millennium BC) was a Proto-Armenian Hurrian-speaking kingdom, known from Assyrian sources beginning in the 13th century BC, located in the Armenian Highland, to the southwest of Lake Van, bordering on Ararat proper. Scholars have linked the district in the area called Arme or Armani, to the name Armenia.

Weidner interpreted textual evidence to indicate that after the Hurrian king Shattuara of Mitanni was defeated by Adad-nirari I of the Middle Assyrian Empire in the early 13th century BC, he then became ruler of a reduced vassal state known as Shubria or Subartu.

Together with Armani-Subartu (Hurri-Mitanni), Hayasa-Azzi and other populations of the region such as the Nairi fell under Urartian (Kingdom of Ararat) rule in the 9th century BC, and their descendants, according to most scholars, later contributed to the ethnogenesis of the Armenians.

Urartu

Urartu corresponding to the biblical Kingdom of Ararat or Kingdom of Van (Urartian: Biai, Biainili) was an Iron Age kingdom centered on Lake Van in the Armenian Highlands. Indeed, Mount Ararat is located in ancient Urartian territory, approximately 120 km north of its former capital.

Strictly speaking, Urartu is the Assyrian term for a geographical region, while “kingdom of Urartu” or “Biainili lands” are terms used in modern historiography for the Urartian-speaking Iron Age state that arose in that region.

This language appears in inscriptions. Though there is no written evidence of any other language being spoken in this kingdom, it is argued on linguistic evidence that Proto-Armenian came in contact with Urartian at an early date.

The landscape corresponds to the mountainous plateau between Asia Minor, Mesopotamia, the Iranian Plateau, and the Caucasus mountains, later known as the Armenian Highlands. The kingdom rose to power in the mid-9th century BC, but was conquered by Media in the early 6th century BC. The heirs of Urartu are the Armenians and their successive kingdoms.

Nairi

In the Assyrian annals the term Uruatri (Urartu) as a name for this league was superseded during a considerable period of years by the term “land of Nairi”. The word is also used to describe the tribes who lived there, whose ethnic identity is uncertain. Nairi has sometimes been equated with Nihriya, known from Mesopotamian, Hittite, and Urartean sources.

The Battle of Nihriya, the culminating point of the hostilities between Hittites and Assyrians for control over the remnants of the former empire of Mitanni, took place there, circa 1230. Nairi was incorporated into Urartu during the 10th century BC.

Mitanni

Mitanni (Hittite cuneiform Mi-ta-an-ni; Mittani Mi-it-ta-ni), also called the Maryannu, Hanigalbat (Hanigalbat, Khanigalbat cuneiform Ḫa-ni-gal-bat) in Assyrian or Naharin in Egyptian texts was a Hurrian-speaking state in northern Syria and southeast Anatolia from ca. 1500 BC–1300 BC.

The Mitanni kingdom was referred to as “nhrn”, which is usually pronounced as Naharin/Naharina from the Assyro-Akkadian word for “river”, cf. Aram-Naharaim or Mitanni by the Egyptians, the Hurri by the Hittites, and the Hanigalbat by the Assyrians. The different names seem to have referred to the same kingdom and were used interchangeably, according to Michael C. Astour.

Another mention by pharaoh Thutmose III of Egypt in the 33rd year of his reign (1446 BC) as the people of Ermenen, and says in their land “heaven rests upon its four pillars”.

The ethnicity of the people of Mitanni is difficult to ascertain. A treatise on the training of chariot horses by Kikkuli contains a number of Indo-Aryan glosses. Kammenhuber (1968) suggested that this vocabulary was derived from the still undivided Indo-Iranian language, but Mayrhofer (1974) has shown that specifically Indo-Aryan features are present.

A Hurrian passage in the Amarna letters – usually composed in Akkadian, the lingua franca of the day – indicates that the royal family of Mitanni was by then speaking Hurrian as well.

Maryannu

Maryannu is an ancient word for the caste of chariot-mounted hereditary warrior nobility which existed in many of the societies of the Middle East during the Bronze Age.

The term is attested in the Amarna letters written by Haapi. Robert Drews writes that the name ‘maryannu’ although plural takes the singular ‘marya’, which in Sanskrit means young warrior, and attaches a Hurrian suffix.

He suggests that at the beginning of the Late Bronze Age most would have spoken either Hurrian or Aryan but by the end of the 14th century most of the Levant maryannu had Semitic names.

Armani

Armani was mentioned alongside Ibla in the geographical treaties of Sargon, this led some historians to identify Ibla with Syrian Ebla and Armani with Syrian Armi. Prof Michael C. Astour refuse to identify Armani with Armi as Naram-Sin makes it clear that the Ibla he sacked (in c.2240 BC) was a border town of the land of Armani, while the Armi in the Eblaite tablets is a vassal to Ebla.

Armani was attested in the treaties of Sargon in a section that mentions regions located in Assyria and Babylonia or territories adjacent to the East in contrast to the Syrian Ebla location in the west. The later King Adad-Nirari I of Assyria also mentions Arman as being located east of the Tigris and on the border between Assyria and Babylon, historians who disagree with the identification of Akkadian Armani with Syrian Armi, place it (along with Akkadian Ibla) north of the Hamrin Mountains in northern Iraq.

It has been suggested by early 20th century Armenologists that Armani is the earliest form of the name Armenia, and that Old Persian Armina and the Greek Armenoi are continuations of an Assyrian toponym Armânum or Armanî.

The earliest attestations of the exonym Armenia date around the 6th century BC. In his trilingual Behistun Inscription, Darius I the Great of Persia refers to Urashtu (in Babylonian) as Armina (in Old Persian) and Harminuya (in Elamite).

Aratta

Aratta is a land that appears in Sumerian myths surrounding Enmerkar and Lugalbanda, two early and possibly mythical kings of Uruk also mentioned on the Sumerian king list. It is described in Sumerian literature as a fabulously wealthy place full of gold, silver, lapis lazuli and other precious materials, as well as the artisans to craft them. It is remote and difficult to reach. It is home to the goddess Inanna, who transfers her allegiance from Aratta to Uruk. It is conquered by Enmerkar of Uruk, according to the Sumerian king list the builder of Uruk in Sumer.

Inanna

Inanna (Neo-Assyrian MUŠ; Sumerian: Inanna; Akkadian: Ištar) was the Sumerian goddess of love, fertility, and warfare, and goddess of the E-Anna temple at the city of Uruk, her main centre. Inanna’s name derives from Lady of Heaven (Sumerian: nin-an-ak). The cuneiform sign of Inanna; however, is not a ligature of the signs lady (Sumerian: nin; Cuneiform: SAL.TUG) and sky (Sumerian: an; Cuneiform: AN). The view that there was a Proto-Euphratean substrate language in Southern Iraq before Sumerian is not widely accepted by modern Assyriologists.

These difficulties have led some early Assyriologists to suggest that originally Inanna may have been a Proto-Euphratean goddess, possibly related to the Hurrian mother goddess Hannahannah, accepted only latterly into the Sumerian pantheon, an idea supported by her youthfulness, and that, unlike the other Sumerian divinities, at first she had no sphere of responsibilities.

Inara

Inara, in Hittite–Hurrian mythology, was the goddess of the wild animals of the steppe and daughter of the Storm-god Teshub/Tarhunt. She corresponds to the “potnia theron” of Greek mythology, better known as Artemis. Inara’s mother is probably Hebat and her brother is Sarruma, meaning “king of the mountains”.

Hannahannah (from Hittite hanna- “grandmother”) is a Hurrian Mother Goddess related to or influenced by the pre-Sumerian goddess Inanna. Hannahannah was also identified with the Hurrian goddess Hebat. Christopher Siren reports that Hannahannah is associated with the Gulses.

Hebat, also transcribed, Kheba or Khepat, was the mother goddess of the Hurrians, known as “the mother of all living”. She is also a Queen of the deities. During Aramaean times Hebat also appears to have become identified with the goddess Hawwah, or Eve.

The Hittite sun goddess Arinniti was later assimilated with Hebat. A prayer of Queen Puduhepa makes this explicit: “To the Sun-goddess of Arinna, my lady, the mistress of the Hatti lands, the queen of Heaven and Earth. Sun-goddess of Arinna, thou art Queen of all countries! In the Hatti country thou bearest the name of the Sun-goddess of Arinna; but in the land which thou madest the cedar land thou bearest the name Hebat.”

Hebat is married to Teshub and is the mother of Sarruma and Alanzu, as well mother-in-law of the daughter of the dragon Illuyanka. The mother goddess is likely to have had a later counterpart in the Phrygian goddess Cybele.

Cybele (Phrygian: Matar Kubileya/Kubeleya “Kubeleyan Mother”, perhaps “Mountain Mother”; Lydian Kuvava; Greek: Kybele, Kybebe, Kybelis) was an originally Anatolian mother goddess; she has a possible precursor in the earliest neolithic at Çatalhöyük (in the Konya region) where the statue of a pregnant goddess seated on a lion throne was found in a granary dated to the 6th millennium BCE.

This corpulent, fertile Mother Goddess appears to be giving birth on her throne, which has two feline-headed hand rests. In Phrygian art of the 8th century BCE, the cult attributes of the Phrygian mother-goddess include attendant lions, a bird of prey, and a small vase for her libations or other offerings.

The mother goddess Hannahannah promises Inara land and a man during a consultation by Inara. Inara then disappears. Her father looks for her, joined by Hannahannah with a bee. The story resembles that of Demeter and her daughter Persephone, in Greek myth.

Ardini

Ardini (likely from Armenian Artin meaning “sun rising” or to “awake”, and it persists in Armenian names to this day) was an ancient city of Urartu, attested in Assyrian sources of the 9th and 8th centuries BC. In Assyrian it was called Muṣaṣir, meaning in Akkadian Exit of the Serpent/Snake.

The mušḫuššu is the sacred animal of Marduk and his son Nabu during the Neo-Babylonian Empire. It was taken over by Marduk from Tishpak, the local god of Eshnunna. MUŠ is the Sumerian term for “serpent”. The mušḫuššu (formerly also read as sirrušu, sirrush) is a creature depicted on the reconstructed Ishtar Gate of the city of Babylon, dating to the 6th century BC.The Babylonian protective spirit, featured prominently on the Ishtar Gate of Babylon, whose name translates as `furious snake’.

At the Babylonian New Year’s festival, the priest was to commission from a woodworker, a metalworker and a goldsmith two images one of which “shall hold in its left hand a snake of cedar, raising its right [hand] to the god Nabu”. In sixth-century Babylon a pair of bronze serpents flanked each of the four doorways of the temple of Esagila. At the Babylonian New Year’s festival, the priest was to commission from a woodworker, a metalworker, and a goldsmith two images, one of which “shall hold in its left hand a snake of cedar, raising its right [hand] to the god Nabu”.

The constellation Hydra was known in Babylonian astronomical texts as MUŠ, “the serpent (with divine and star determinatives)”. It was depicted as a snake drawn out long with the forepaws of a lion, no hind-legs, with wings, and with a head comparable to the mušḫuššu dragon. This monstrous serpent may have inspired the Lernaean Hydra of Greek mythology and ultimately the modern Hydra constellation.

The Mushhushshu was a creature shaped like a slender dog with a scaly body and tail, bird’s talons, a long neck, forked tongue and a protruding horn. The god who controlled the Mushhushshu was considered the supreme god and so many early gods were associated with this creature until, finally, it became linked with Marduk.

Khaldi

The city’s tutelary deity was Ḫaldi, also known as Khaldi or Hayk, one of the three chief deities of Ararat (Urartu). Hayk or Hayg, also known as Haik Nahapet (Hayk the Tribal Chief), is the legendary patriarch and founder of the Armenian nation.

Hayasa-Azzi or Azzi-Hayasa was a Late Bronze Age confederation formed between two kingdoms of Armenian Highlands, Hayasa located South of Trabzon and Azzi, located north of the Euphrates and to the south of Hayasa.

The similarity of the name Hayasa to the endonym of the Armenians, Hayk or Hay and the Armenian name for Armenia, Hayastan has prompted the suggestion that the Hayasa-Azzi confereration was involved in the Armenian ethnogenesis.

The term Hayastan bears resemblance to the ancient Mesopotamian god Haya (ha-ià) and another western deity called Ebla Hayya, related to the god Ea (Enki or Enkil in Sumerian, Ea in Akkadian and Babylonian).

Thus, the Great Soviet Encyclopedia of 1962 posited that the Armenians derive from a migration of Hayasa into Shupria in the 12th century BC. This is open to objection due to the possibility of a mere coincidental similarity between the two names and the lack of geographic overlap, although Hayasa (the region) became known as Lesser Armenia (Pokr Hayastan in modern Armenian) in coming centuries.

Scholars such as Carl Ferdinand Friedrich Lehmann-Haupt (1910) believed that the people of Urartu called themselves Khaldini after their god Khaldi. Boris Piotrovsky wrote that “the Urartians first appear in history as a league of tribes or countries which did not yet constitute a unitary state in the 13th century BC.

Ishara

Ishara is the Hittite word for “treaty, binding promise”, also personified as a goddess of the oath. Ishara is an ancient deity of unknown origin from northern modern Syria. She first appeared in Ebla and was incorporated to the Hurrian pantheon from which she found her way to the Hittite pantheon.

In Hurrian and Semitic traditions, Išḫara is a love goddess, often identified with Ishtar. Her cult was of considerable importance in Ebla from the mid 3rd millennium, and by the end of the 3rd millennium, she had temples in Nippur, Sippar, Kish, Harbidum, Larsa, and Urum.

Ishara became a great goddess of the Hurrian population. She was associated with the underworld. Her astrological embodiment is the constellation Scorpio and she is called the mother of the Sebitti (the Seven Stars).

The etymology of Ishara is unknown. The goddess appears from as early as the mid 3rd millennium as one of the chief goddesses of Ebla, and her name appears as an element in theophoric names in Mesopotamia in the later 3rd millennium (Akkad period), and into the first (Assyria), as in Tukulti-apil-esharra (i.e., Tiglath-Pileser).

Variants of the name appear as Ašḫara (in a treaty of Naram-Sin of Akkad with Hita of Elam) and Ušḫara (in Ugarite texts). In Ebla, there were various logographic spellings involving the sign AMA “mother”. In Alalah, her name was written with the Akkadogram IŠTAR plus a phonetic complement -ra, as IŠTAR-ra.

One of the most important goddesses of reconstructed Proto-Indo-European religion is the personification of dawn as a beautiful young woman. Her name is reconstructed as Hausōs (PIE *h₂ewsṓs- or *h₂ausōs-, an s-stem), besides numerous epithets.

Derivatives of *h₂ewsṓs in the historical mythologies of Indo-European peoples include Indian Uṣas, Greek Eōs, Latin Aurōra, and Baltic Aušra (“dawn”, c.f. Lithuanian Aušrinė). Germanic *Austrōn- is from an extended stem *h₂ews-tro-.

The name *h₂ewsṓs is derived from a root *h₂wes / *au̯es “to shine”, thus translating to “the shining one”. Both the English word east and the Latin auster “south” are from a root cognate adjective *aws-t(e)ro-. Also cognate is aurum “gold”, from *awso-. The name for “spring season”, *wes-r- is also from the same root. The dawn goddess was also the goddess of spring, involved in the mythology of the Indo-European new year, where the dawn goddess is liberated from imprisonment by a god (reflected in the Rigveda as Indra, in Greek mythology as Dionysus and Cronus).

Besides the name most amenable to reconstruction, *h₂ewsṓs, a number of epithets of the dawn goddess may be reconstructed with some certainty. Among these is *wenos- (also an s-stem), whence Sanskrit vanas “loveliness; desire”, used of Uṣas in the Rigveda, and the Latin name Venus and the Norse Vanir. The name indicates that the goddess was imagined as a beautiful nubile woman, who also had aspects of a love goddess.

The abduction and imprisonment of the dawn goddess, and her liberation by a heroic god slaying the dragon who imprisons her, is a central myth of Indo-European religion, reflected in numerous traditions. Most notably, it is the central myth of the Rigveda, a collection of hymns surrounding the Soma rituals dedicated to Indra in the New Year celebrations of the early Indo-Aryans.

Shivini

Shivini or Artinis (the present form of the name is Artin, meaning “sun rising” or to “awake”, and it persists in Armenian names to this day) was a solar god in the mythology of the Urartu. He is the third god in a triad with Khaldi and Theispas and is cognate with the triad in Hinduism called Shivam.

He was depicted as a man on his knees, holding up a solar disc. His wife was most likely a goddess called Tushpuea. The Assyrian god Shamash is a counterpart to Shivini. Shivini is generally considered a good god, like the Egyptian solar god, Aten, and unlike the solar god of the Assyrians, Ashur to whom sometimes human sacrifices were made.

Shiva

Shiva (“The Auspicious One”), also known as Mahadeva (“Great God”), is one of the main deities of Hinduism. He is the supreme god within Shaivism, one of the three most influential denominations in contemporary Hinduism.

He is one of the five primary forms of God in the Smarta tradition, and “the Destroyer” or “the Transformer” among the Trimurti, the Hindu Trinity of the primary aspects of the divine.

At the highest level, Shiva is regarded as limitless, transcendent, unchanging and formless. Shiva also has many benevolent and fearsome forms. In benevolent aspects, he is depicted as an omniscient Yogi who lives an ascetic life on Mount Kailash, as well as a householder with wife Parvati and his two children, Ganesha and Kartikeya, and in fierce aspects, he is often depicted slaying demons. Shiva is also regarded as the patron god of yoga and arts.

The main iconographical attributes of Shiva are the third eye on his forehead, the snake Vasuki around his neck, the adorning crescent moon, the holy river Ganga flowing from his matted hair, the trishula as his weapon and the damaru as his musical instrument. Shiva is usually worshiped in the aniconic form of Lingam.

According to Wendy Doniger, the Puranic Shiva is a continuation of the Vedic Indra. She gives several reasons for her hypothesis. Both are associated with mountains, rivers, male fertility, fierceness, fearlessness, warfare, transgression of established mores, the Aum sound, the Supreme Self.

The figure of Shiva as we know him today was built up over time, with the ideas of many regional sects being amalgamated into a single figure. Shiva became identified with countless local cults by the sheer suffixing of Isa or Isvara to the name of the local deity, e.g., Bhutesvara, Hatakesvara, Chandesvara.”

An example of assimilation took place in Maharashtra, where a regional deity named Khandoba is a patron deity of farming and herding castes. The foremost center of worship of Khandoba in Maharashtra is in Jejuri.

Khandoba has been assimilated as a form of Shiva himself, in which case he is worshipped in the form of a lingam. Khandoba’s varied associations also include an identification with Surya (“the Supreme Light”), also known as Aditya, Bhanu or Ravi Vivasvana in Sanskrit, and in Avestan Vivanhant, the chief solar deity in Hinduism and generally refers to the Sun, and Karttikeya, also known as Skanda, Kumaran, Kumara Swami and Subramaniyan, the Hindu god of war.

Kartikeya (Sanskrit Kārtikēya “son of Kṛttikā” Tamil: Kārttikēyaṉ), is the Commander-in-Chief of the army of the devas and the son of Shiva and Parvati. Murugan (Tamil Murukaṉ) is often referred to as Tamiḻ kaṭavuḷ’ (“god of the Tamils”).

The first elaborate account of Kartikeya’s origin occurs in the Mahabharata. In a complicated story, he is said to have been born from Agni and Svaha, after the latter impersonated the six of the seven wives of the Saptarishi (Seven Sages). The actual wives then become the Pleiades.

Surya

Surya (“the Supreme Light”), also known as Aditya, Bhanu or Ravi Vivasvana in Sanskrit, and in Avestan Vivanhant, is the chief solar deity in Hinduism and generally refers to the Sun. “Arka” form is worshiped mostly in North India and Eastern parts of India.

Surya is the chief of the Navagraha, the nine Indian Classical planets and important elements of Hindu astrology. He is often depicted riding a chariot harnessed by seven horses which might represent the seven colors of the rainbow or the seven chakras in the body. He is also the presiding deity of Sunday.

Surya is regarded as the Supreme Deity by Saura sect and Smartas worship him as one of the five primary forms of God. The sun god, Zun, worshipped by the Afghan Zunbil dynasty, is thought to be synonymous with Surya.

Surya had three wives: Saranyu, Ragyi and Prabha. Saranyu was the mother of Vaivasvata Manu (the seventh, i.e., present Manu) and the twins Yama (the Lord of Death) and his sister Yami. She also bore him the twins known as the Ashvins, divine horsemen and physicians to the Devas.

Saranyu, being unable to bear the extreme radiance of Surya, created a superficial entity from her shadow called Chhaya and instructed her to act as Surya’s wife in her absence. Chhaya mothered two sons Savarni Manu (the eighth, i.e., next Manu) and Shani (the planet Saturn), and two daughters, Tapti and Vishti.

He has two more sons, Revanta with Ragy, and Prabhata with Prabha. Surya is the father of the famous tragic hero Karna, described in the Indian epic Mahabharata, by a human princess named Kunti.

Surya’s sons, Shani and Yama, are responsible for the judgment of human life. Shani provides the results of one’s deeds during one’s life through appropriate punishments and rewards while Yama grants the results of one’s deeds after death.

Rudras and Marutas

In the Rig Veda the term śiva is used to refer to Indra. Indra, like Shiva, is likened to a bull. In the Rig Veda, Rudra is the father of the Maruts, but he is never associated with their warlike exploits as is Indra, an ancient Vedic deity who later came to be identified with Shiva.

Rudras are forms and followers of the god Rudra-Shiva and make eleven of the Thirty-three gods in the Hindu pantheon. They are at times identified with the Maruts – sons of Rudra; while at other times, considered distinct from them.

The number of Marutas varies from 27 to sixty (three times sixty in RV 8.96.8). They are very violent and aggressive, described as armed with golden weapons i.e. lightning and thunderbolts, as having iron teeth and roaring like lions, as residing in the north, as riding in golden chariots drawn by ruddy horses.

In the Vedic mythology, the Marutas, a troop of young warriors, are Indra’s companions. According to French comparative mythologist Georges Dumézil, they are cognate to the Einherjar and the Wild hunt.

According to the Rig Veda, the ancient collection of sacred hymns, they wore golden helmets and breastplates, and used their axes to split the clouds so that rain could fall. They were widely regarded as clouds, capable to shaking mountains and destroying forests.

According to later tradition, such as Puranas, the Marutas were born from the broken womb of the goddess Diti, after Indra hurled a thunderbolt at her to prevent her from giving birth to too powerful a son. The goddess had intended to remain pregnant for a century before giving birth to a son who would threaten Indra.

Vahana

Vah in Sanskrit means to carry or to transport. Vahana (literally “that which carries, that which pulls”) denotes the being, typically an animal or mythical entity, a particular Hindu deity is said to use as a vehicle. In this capacity, the vahana is often called the deity’s “mount”.

Upon the partnership between the deity and his vahana it is woven much iconography and mythology. Often, the deity is iconographically depicted riding (or simply mounted upon) the vahana. Other times, the vahana is depicted at the deity’s side or symbolically represented as a divine attribute.

The vahana may be considered an accoutrement of the deity: though the vahana may act independently, they are still functionally emblematic or even syntagmatic of their “rider”. The deity may be seen sitting or on, or standing on, the vahana. They may be sitting on a small platform called a howdah, or riding on a saddle or bareback.

In Hindu iconography, positive aspects of the vehicle are often emblematic of the deity that it carries. Nandi the bull, vehicle of Shiva, represents strength and virility. Parvani the peacock, vehicle of Skanda, represents splendor and majesty. However, the vehicle animal also symbolizes the evil forces over which the deity dominates.

The vahana and deity to which they support are in a reciprocal relationship. Vahana serve and are served in turn by those who engage them. Many vahana may also have divine powers or a divine history of their own.

Ashvah

Aśvaḥ is the Sanskrit word for a horse, one of the significant animals finding references in the Vedas as well as later Hindu scriptures. The corresponding Avestan term is aspa. The word is cognate to Latin equus, Greek hippos, Germanic *ehwaz and Baltic *ašvā all from PIE *hek’wos.

There are repeated references to the horse the Vedas (c. 1500 – 500 BC). In particular the Rigveda has many equestrian scenes, often associated with chariots. The Ashvins are divine twins named for their horsemanship. The earliest undisputed finds of horse remains in South Asia are from the Swat culture (c. 1500 – 500 BC).

The legend states that the first horse emerged from the depth of the ocean during the churning of the oceans. It was a horse with white color and had two wings. It was known by the name of Uchchaihshravas.

The legend continues that Indra, king of the devas, took away the mythical horse to his celestial abode, the svarga (heaven). Subsequently, Indra severed the wings of the horse and presented the same to the mankind. The wings were severed to ensure that the horse would remain on the earth (prithvi) and not fly back to Indra’s svarga.

In Hinduism, Svarga, also known as Swarga Loka, is any of the seven loka or planes in Hindu cosmology. It is a set of heavenly worlds located on and above Mt. Meru. It is a heaven where the righteous live in a paradise before their next incarnation.

During each pralaya, the great dissolution, the first three realms, Bhu loka (Earth), Bhuvar loka, and Swarga loka, are destroyed. Below the seven upper realms lie seven lower realms, of Patala, the underworld and netherworld.

Svarga is seen as a transitory place for righteous souls who have performed good deeds in their lives but are not yet ready to attain moksha, or elevation to Vaikunta, the abode of Lord Vishnu, considered to be the Supreme Abode. The capital of Svarga is Amaravati and its entrance is guarded by Airavata. Svarga is presided over by Indra, the chief deva.

Ashvins

The Ashvins or Ashwini Kumaras (Sanskrit: aśvin-, dual aśvinau), in Hindu mythology, are two Vedic gods, divine twin horsemen in the Rigveda, sons of Saranyu (daughter of Vishwakarma), a goddess of the clouds and wife of Surya in his form as Vivasvant.

They symbolise the shining of sunrise and sunset, appearing in the sky before the dawn in a golden chariot, bringing treasures to men and averting misfortune and sickness. They are the doctors of gods and are devas of Ayurvedic medicine.

They are represented as humans with head of a horse. In the epic Mahabharata, King Pandu’s wife Madri is granted a son by each Ashvin and bears the twins Nakula and Sahadeva who, along with the sons of Kunti, are known as the Pandavas.

They are also called Nasatya (dual nāsatyau “kind, helpful”) in the Rigveda; later, Nasatya is the name of one twin, while the other is called Dasra (“enlightened giving”). By popular etymology, the name nāsatya is often incorrectly analysed as na+asatya “not untrue”=”true”.

Various Indian holy books like Mahabharat, Puranas etc., relate that Ashwini Kumar brothers, the twins, who were RajVaidhya (Royal Physicians) to Devas during Vedic times, first prepared Chyawanprash formulation for Chyawan Rishi at his Ashram on Dhosi Hill near Narnaul, Haryana, India, hence the name Chyawanprash.

The Ashvins can be compared with the Dioscuri (the twins Castor and Pollux) of Greek and Roman mythology, and especially to the divine twins Ašvieniai of the ancient Baltic religion.

The Ashvins are mentioned 376 times in the Rigveda. The Nasatya twins are invoked in a treaty between Suppiluliuma and Shattiwaza, kings of the Hittites and the Mitanni respectively.

Ashvini is the first nakshatra (lunar mansion) in Hindu astrology having a spread from 0°-0′-0″ to 13°-20′, corresponding to the head of Aries, including the stars β and γ Arietis.

The name aśvinī is used by Varahamihira (6th century). The older name of the asterism, found in the Atharvaveda (AVS 19.7; in the dual) and in Panini (4.3.36), was aśvayúj “harnessing horses”.

Ashvini is ruled by Ketu, the descending lunar node. In electional astrology, Asvini is classified as a Small constellation, meaning that it is believed to be advantageous to begin works of a precise or delicate nature while the moon is in Ashvini.

Asvini is ruled by the Ashvins, the heavenly twins who served as physicians to the gods. Personified, Asvini is considered to be the wife of the Asvini Kumaras. Ashvini is represented either by the head of a horse, or by honey and the bee hive.

Ashvamedha

The Ashvamedha was one of the most important royal rituals of the Hindu Vedic religion, described in detail in the Yajurveda and the pertaining commentary in the Shatapatha Brahmana. The Rigveda does have descriptions of horse sacrifice, but does not allude to the full ritual according to the Yajurveda. As per Brahma Vaivarta Purana, the Ashvamedha is one of five rites forbidden in the Kali Yuga, the present age.

The Ashvamedha could only be conducted by a king (rājā). Its object was the acquisition of power and glory, the sovereignty over neighbouring provinces, seeking progeny and general prosperity of the kingdom.

Raja

Raja is a term for a monarch or princely rulers in South and Southeast Asia. Rana is practically equivalent, and the female form rani (sometimes spelled ranee) applies equally to the wife of a raja or rana. Maharaja, or “great king” is in theory a title for more significant rulers in India, but after some inflation of titles over time, there is no clear difference between the terms. The title has a long history in the Indian subcontinent and South East Asia, being attested from the Rigveda, where a rājan- is a ruler.

Sanskrit rājan- is cognate to Latin rēx (genitive rēgis), Gaulish rīx, Gaelic rí (genitive ríg), etc., originally denoting heads of petty kingdoms and city states. It is believed to be ultimately derived from the Proto-Indo-European *h3rēǵs, a vrddhi formation to the root *h3reǵ- “to straighten, to order, to rule”.

The Sanskrit n-stem is secondary in the male title, apparently adapted from the female counterpart rājñī which also has an -n- suffix in related languages, compare Old Irish rígain and Latin regina. Cognates of the word Raja in other Indo-European languages include English reign and German reich.

Asuras

Asuras are mythological lord beings in Indian texts who compete for power with the more benevolent devas (also known as suras). Asuras are described in Indian texts as powerful superhuman creatures with good or bad qualities, the good ones are called Adityas and led by Varuna, while the bad malevolent ones are called Danavas and led by Vrtra.

In the earliest layer of Vedic texts, Agni, Indra and other gods are also called Asura, in the sense of they being “lords” of their domain, knowledge and abilities. In later Vedic and post-Vedic texts, the benevolent gods are called Devas, while malevolent Asuras compete against these Devas and are considered “enemy of the gods” or demons.

Asura, some scholars such as Asko Parpola suggest may be related to proto-Uralic and proto-Norse history. The Aesir-Asura correspondence is the relation between Asura of Vedic Sanskrit to Æsir, an Old Norse that is – old German and Scandinavian – word, and *asera or *asira of proto-Uralic languages all of which mean “lord, powerful spirit, god”.

Parpola states that the correspondence extends beyond Asera-Asura, and extends to a host of parallels such as Inmar-Indra, Sampas-Stambha and many other elements of respective mythologies.

Indra

The Bactria-Margiana Culture, also called “Bactria-Margiana Archaeological Complex”, was a non-Indo-European culture which influenced the Indo-European groups of the second stage of the Indo-European migrations. It was centered in what is nowadays northwestern Afghanistan and southern Turkmenistan. Proto-Indo-Iranian arose due to this influence.

The Vedic beliefs and practices of the pre-classical era were closely related to the hypothesised Proto-Indo-European religion, and the Indo-Iranian religion. The Indo-Iranians also borrowed their distinctive religious beliefs and practices from this culture. According to Anthony, the Old Indic religion probably emerged among Indo-European immigrants in the contact zone between the Zeravshan River (present-day Uzbekistan) and (present-day) Iran.

It was “a syncretic mixture of old Central Asian and new Indo-European elements”, which borrowed “distinctive religious beliefs and practices” from the Bactria–Margiana Culture. At least 383 non-Indo-European words were borrowed from this culture, including the god Indra and the ritual drink Soma.

Many of the qualities of Indo-Iranian god of might/victory, Verethraghna, were transferred to the adopted god Indra, who became the central deity of the developing Old Indic culture. Indra was the subject of 250 hymns, a quarter of the Rig Veda. He was associated more than any other deity with Soma, a stimulant drug (perhaps derived from Ephedra) probably borrowed from the BMAC religion. His rise to prominence was a peculiar trait of the Old Indic speakers.

Ishvara

Ishvara is a concept in Hinduism, with a wide range of meanings that depend on the era and the school of Hinduism. In ancient texts of Indian philosophy, Ishvara means supreme soul, Brahman (Highest Reality), ruler, king or husband depending on the context.

In medieval era texts, Ishvara means God, Supreme Being, personal god, or special Self depending on the school of Hinduism. In Shaivism, Ishvara is synonymous with “Shiva”, as the “Supreme lord over other Gods” in the pluralistic sense, or as an Ishta-deva in pluralistic thought. In Vaishnavism, it is synonymous with Vishnu.

In traditional Bhakti movements, Ishvara is one or more deities of an individual’s preference from Hinduism’s polytheistic canon of deities. In modern sectarian movements such as Arya Samaj and Brahmoism, Ishvara takes the form of a monotheistic God.

In Yoga school of Hinduism, it is any “personal deity” or “spiritual inspiration”. In Advaita Vedanta school Ishvara is a monistic Universal Absolute that connects and is the Oneness in everyone and everything.

The root of the word Ishvara comes from īś- (ईश, Ish) which means “capable of” and “owner, ruler, chief of”, ultimately cognate with English own (Germanic *aigana-, PIE *aik-).

The second part of the word Ishvara is vara which means depending on context, “best, excellent, beautiful”, “choice, wish, blessing, boon, gift”, and “suitor, lover, one who solicits a girl in marriage”. The composite word, Ishvara literally means “owner of best, beautiful”, “ruler of choices, blessings, boons”, or “chief of suitor, lover”.

As a concept, Ishvara in ancient and medieval Sanskrit texts, variously means God, Supreme Being, Supreme Soul, lord, king or ruler, rich or wealthy man, god of love, deity Shiva, one of the Rudras, prince, husband and the number eleven.

The word Īśvara never appears in Rigveda. However, the verb īś- does appear in Rig veda, where the context suggests that the meaning of it is “capable of, able to”. It is absent in Samaveda, is rare is Atharvaveda, appears in Samhitas of Yajurveda. The contextual meaning, however as the ancient Indian grammarian Pāṇini explains, is neither god nor supreme being.

The word Īśvara appears in numerous ancient Dharmasutras. However, Patrick Olivelle states that there Ishvara does not mean God, but means Vedas. Deshpande states that Ishvara in Dharmasutras could alternatively mean king, with the context literally asserting that “the Dharmasutras are as important as Ishvara (the king) on matters of public importance”.

In Saivite traditions of Hinduism, the term is used as part of the compound “Maheshvara” (“great lord”) as a name for Shiva. In Mahayana Buddhism it is used as part of the compound “Avalokiteśvara” (“lord who hears the cries of the world”), the name of a bodhisattva revered for her compassion. When referring to divine as female, particularly in Shaktism, the feminine Īśvarī is sometimes used.

Isuwa

Isuwa (transcribed Išuwa and sometimes rendered Ishuwa) was the ancient Hittite name for one of its neighboring Anatolian kingdoms to the east, in an area which later became the Luwian Neo-Hittite state of Kammanu.

The land of Isuwa was situated in the upper Euphrates river region. The river valley was here surrounded by the Anti-Taurus Mountains. To the northeast of the river lay a vast plain stretching up to the Black Sea mountain range.

The plain had favourable climatic conditions due to the abundance of water from springs and rainfall. Irrigation of fields was possible without the need to build complex canals. The river valley was well suited for intensive agriculture, while livestock could be kept at the higher altitudes. The mountains possessed rich deposits of copper which were mined in antiquity.

The Isuwans left no written record of their own, and it is not clear which of the Anatolian peoples inhabited the land of Isuwa prior to the Luwians. They could have been Indo-Europeans like the Luwians, related to the Hittites to the west, Hattians, Hurrians from the south, or Urartians who lived east of Isuwa in the first millennium BC.

The area was one of the places where agriculture developed very early in the Neolithic period. Urban centres emerged in the upper Euphrates river valley around 3000 BC. The first states may have followed in the third millennium BC. The name Isuwa is not known until the literate Hittite period of the second millennium BC. Few literate sources from within Isuwa have been discovered and the primary source material comes from Hittite texts.

The earliest settlements in Isuwa show cultural contacts with Tell Brak to the south, though not being the same culture. Agriculture began early due to favorable climatic conditions. Isuwa was at the outer fringe of the early Mesopotamian Uruk period culture.

The people of Isuwa were also skilled in metallurgy and they reached the Bronze Age in the fourth millennium BC. Copper were first mixed with arsenic, later with tin. The Early Bronze Age culture was linked with Caucasus in the northeast.

In the Hittite period the culture of Isuwa shows great parallels to the Central Anatolian and the Hurrian culture to the south. The monumental architecture was of Hittite influence. The Neo-Hittite state show influences both from the Phrygia, Assyria and the eastern kingdom of Urartu. After the Scythian people movement there appear some Scythian burials in the area.

Aššur

Aššur, also known as Ashur, Qal’at Sherqat and Kalah Shergat, is a remnant city of the last Ashurite Kingdom. Aššur is also the name of the chief deity of the city. He was considered the highest god in the Assyrian pantheon and the protector of the Assyrian state.

The remains of the city are situated on the western bank of the river Tigris, north of the confluence with the tributary Little Zab river, in modern-day Iraq, more precisely in the Al-Shirqat District (a small panhandle of the Salah al-Din Governorate).

The city was occupied from the mid-3rd millennium BC (Circa 2600–2500 BC) to the 14th Century AD, when Tamurlane conducted a massacre of its population.

Archaeology reveals the site of the city was occupied by the middle of the third millennium BC. This was still the Sumerian period, before the Assyrian kingdom emerged in the 23rd to 21st century BC.

The oldest remains of the city were discovered in the foundations of the Ishtar temple, as well as at the Old Palace. In the following Old Akkadian period, the city was ruled by kings from Akkad. During the “Sumerian Renaissance”, the city was ruled by a Sumerian governor.

Aššur is the name of the city, of the land ruled by the city, and of its tutelary deity. At a late date it appears in Assyrian literature in the forms An-sar, An-sar (ki), which form was presumably read Assur. The name of the deity is written A-šur or Aš-sùr, and in Neo-assyrian often shortened to Aš.

In the Creation tablet, the heavens personified collectively were indicated by this term An-sar, “host of heaven,” in contradistinction to the earth, Ki-sar, “host of earth.”

In view of this fact, it seems highly probable that the late writing An-sar for Assur was a more or less conscious attempt on the part of the Assyrian scribes to identify the peculiarly Assyrian deity Asur with the Creation deity An-sar.

On the other hand, there is an epithet Asir or Ashir (“overseer”) applied to several gods and particularly to the deity Asur, a fact which introduced a third element of confusion into the discussion of the name Assur. It is probable then that there is a triple popular etymology in the various forms of writing the name Assur; viz. A-usar, An-sar and the stem asdru.

Syria

The name Syria has since the Roman Empire’s era historically referred to the region of Syria. It is the Latinized from the original Indo-Anatolian and later Greek Συρία. Etymologically and historically, the name is accepted by majority mainstream academic opinion as having derived from Ασσυρία, Assuria/Assyria, from the Akkadian Aššur or Aššūrāyu, which is in fact located in Upper Mesopotamia (modern northern Iraq southeast Turkey and northeast Syria).

Majority mainstream scholarly opinion now strongly supports the already dominant position that ‘Syrian’ and Syriac indeed derived from ‘Assyrian’, and the 21st Century discovery of the Çineköy inscription seems to clearly confirm that Syria is ultimately derived from the Assyrian term Aššūrāyu.

The question was addressed from the Early Classical period through to the Renaissance Era by the likes of Herodotus, Strabo, Justinus, Michael the Syrian and John Selden, with each of these stating that Syrian/Syriac was synonymous and derivative of Assyrian. It was concluded that the Indo-European term Syrian was a derived from the much earlier Assyrian.

Some 19th-century historians such as Ernest Renan had dismissed the etymological identity of the two toponyms. Various alternatives had been suggested, including derivation from Subartu (a term which most modern scholars in fact accept is itself an early name for Assyria, and which was located in northern Mesopotamia), the Hurrian toponym Śu-ri, or Ṣūr (the Phoenician name of Tyre). Syria is known as Ḫrw (Ḫuru, referring to the Hurrian occupants prior to the Aramaean invasion) in the Amarna Period Egypt, and as Aram in Biblical Hebrew.

A. Tvedtnes had suggested that the Greek Suria is loaned from Coptic, and due to a regular Coptic development of Ḫrw to *Šuri. In this case, the name would directly derive from that of the Language Isolate speaking Hurrians, and be unrelated to the name Aššur. Tvedtnes’ explanation was rejected as highly unlikely by Frye in 1992.

Various theories have been advanced as to the etymological connections between the two terms. Some scholars suggest that the term Assyria included a definite article, similar to the function of the Arabic language “Al-“.

Theodor Nöldeke in 1881 gave philological support to the assumption that Syria and Assyria have the same etymology, a suggestion going back to John Selden (1617) rooted in his own Hebrew tradition about the descent of Assyrians from Jokshan.

Majority and mainstream current academic opinion strongly favours that Syria originates from Assyria. A Hieroglyphic Luwian and Phoenician bilingual monumental inscription found in Çineköy, Turkey, (the Çineköy inscription) belonging to Urikki, vassal king of Que (i.e. Cilicia), dating to the eighth century BC, reference is made to the relationship between his kingdom and his Assyrian overlords.

The Luwian inscription reads su-ra/i whereas the Phoenician translation reads ʾšr, i.e. ašur, which according to Robert Rollinger (2006) “settles the problem once and for all”.This view is also supported by Aziz Suryal Atiya, Silvio Zaorani, Encyclopedia Americana

Marduk/Sarpanit

In the Mesopotamian mythology Ashur was the equivalent of Babylonian Marduk (Sumerian spelling in Akkadian: AMAR.UTU “solar calf”), a late-generation god from ancient Mesopotamia and patron deity of the city of Babylon. The Ésagila, a Sumerian name signifying “E (temple) whose top is lofty”, (literally: “house of the raised head”) was a temple dedicated to Marduk, the protector god of Babylon.

Marduk’s original character is obscure but he was later associated with water, vegetation, judgment, and magic. His consort was the goddess Sarpanit. Her name means “the shining one”, and she is sometimes associated with the planet Venus.

By a play on words her name was interpreted as zēr-bānītu, or “creatress of seed”, and is thereby associated with the goddess Aruru, who, according to Babylonian myth, created mankind. Her marriage with Marduk was celebrated annually at New Year in Babylon. She was worshipped via the rising moon, and was often depicted as being pregnant. She is also known as Erua. She may be the same as Gamsu, Ishtar, and/or Beltis.

Marduk was also regarded as the son of Ea (Sumerian Enki) and Damkina and the heir of Anu, but whatever special traits Marduk may have had were overshadowed by the political development through which the Euphrates valley passed and which led to people of the time imbuing him with traits belonging to gods who in an earlier period were recognized as the heads of the pantheon. There are particularly two gods—Ea and Enlil—whose powers and attributes pass over to Marduk.

In the case of Ea, the transfer proceeded pacifically and without effacing the older god. Marduk took over the identity of Asarluhi, the son of Ea and god of magic, so that Marduk was integrated in the pantheon of Eridu where both Ea and Asarluhi originally came from. Father Ea voluntarily recognized the superiority of the son and hands over to him the control of humanity.

This association of Marduk and Ea, while indicating primarily the passing of the supremacy once enjoyed by Eridu to Babylon as a religious and political centre, may also reflect an early dependence of Babylon upon Eridu, not necessarily of a political character but, in view of the spread of culture in the Euphrates valley from the south to the north, the recognition of Eridu as the older centre on the part of the younger one.

While the relationship between Ea and Marduk is marked by harmony and an amicable abdication on the part of the father in favour of his son, Marduk’s absorption of the power and prerogatives of Enlil of Nippur was at the expense of the latter’s prestige. Babylon became independent in the early 19th century BC, and was initially a small city state, overshadowed by older and more powerful Mesopotamian states such as Isin, Larsa and Assyria.

However, after Hammurabi forged an empire in the 18th century BC, turning Babylon into the dominant state in the south, the cult of Marduk eclipsed that of Enlil; although Nippur and the cult of Enlil enjoyed a period of renaissance during the over four centuries of Kassite control in Babylonia (c. 1595 BC–1157 BC), the definite and permanent triumph of Marduk over Enlil became felt within Babylonia.

The only serious rival to Marduk after ca. 1750 BC was the god Aššur (Ashur) (who had been the supreme deity in the northern Mesopotamian state of Assyria since the 25th century BC) which was the dominant power in the region between the 14th to the late 7th century BC.

In the south, Marduk reigned supreme. He is normally referred to as Bel “Lord”, also bel rabim “great lord”, bêl bêlim “lord of lords”, ab-kal ilâni bêl terêti “leader of the gods”, aklu bêl terieti “the wise, lord of oracles”, muballit mîte “reviver of the dead”, etc.

When Babylon became the principal city of southern Mesopotamia during the reign of Hammurabi in the 18th century BC, the patron deity of Babylon was elevated to the level of supreme god. In order to explain how Marduk seized power, Enûma Elish was written, which tells the story of Marduk’s birth, heroic deeds and becoming the ruler of the gods. This can be viewed as a form of Mesopotamian apologetics. Also included in this document are the fifty names of Marduk.

In Enûma Elish, a civil war between the gods was growing to a climactic battle. The Anunnaki gods gathered together to find one god who could defeat the gods rising against them. Marduk, a very young god, answered the call and was promised the position of head god.

To prepare for battle, he makes a bow, fletches arrows, grabs a mace, throws lightning before him, fills his body with flame, makes a net to encircle Tiamat within it, gathers the four winds so that no part of her could escape, creates seven nasty new winds such as the whirlwind and tornado, and raises up his mightiest weapon, the rain-flood. Then he sets out for battle, mounting his storm-chariot drawn by four horses with poison in their mouths. In his lips he holds a spell and in one hand he grasps a herb to counter poison.

First, he challenges the leader of the Anunnaki gods, the dragon of the primordial sea Tiamat, to single combat and defeats her by trapping her with his net, blowing her up with his winds, and piercing her belly with an arrow.

Then, he proceeds to defeat Kingu, who Tiamat put in charge of the army and wore the Tablets of Destiny on his breast, and “wrested from him the Tablets of Destiny, wrongfully his” and assumed his new position. Under his reign humans were created to bear the burdens of life so the gods could be at leisure.

Marduk was depicted as a human, often with his symbol the snake-dragon which he had taken over from the Akkadian god Tishpak, likely, identical with the Hurrian god “Teshup”. Another symbol that stood for Marduk was the spade. In the perfected system of astrology, the planet Jupiter was associated with Marduk by the Hammurabi period.

Babylonian texts talk of the creation of Eridu by the god Marduk as the first city, “the holy city, the dwelling of their [the other gods] delight”.

Nabu/Tashmetum

Nabu is the Assyrian and Babylonian god of wisdom and writing, worshipped by Babylonians as the son of Marduk and Sarpanitum and as the grandson of Ea. Nabu’s name is derived from the Semitic root nb´, meaning “to name/designate”, “announcer/herald”, “the one who is named/designated”, “to call”, and “to proclaim”.

Nabu resided in his temple of Ezida in Borsippa and also had several temples devoted to him throughout Assyria and beyond. Due to his role as Marduk’s minister and scribe, Nabu became the god of wisdom and writing (including religious, scientific and magical texts) taking over the role from the Sumerian goddess Nisaba.

Nabu was also worshipped as a god of fertility, a god of water, and a god of vegetation. He was also the keeper of the Tablets of Destiny, which recorded the fate of mankind and allowed him to increase or diminish the length of human life. His symbols are the clay tablet and stylus.

The planet Mercury, associated with Babylonian Nabu (the son of Marduk) was in Sumerian times, identified with Enki. As Enki also Nabu was identified by the Greeks with Hermes, by the Romans with Mercury, and by the Egyptians with Thoth.

Nabu’s consort was Tashmetum. She is called upon to listen to prayers and to grant requests. Tashmetum and Nabu both shared a temple in the city of Borsippa, in which they were patron deities. Tashmetum’s name means “the lady who listens”. She is also known as Tashmit and Tashmetu, and she was known by the epithets Lady of Hearing and Lady of Favor.

Tushpuea is an Araratian (Urartian) goddess from which the city of Tushpa derived its name. She may have been the wife of the solar god Shivini as both are listed as third, in the list of male and female deities on the Mheri-Dur inscription. It is hypothesized that the winged female figures on Urartian ornaments and cauldrons depict this goddess.

Leave a comment