Orion, the bull and the three kings

Posted by Sjur Cappelen Papazian on March 20, 2014

Orion raises his club and shield against the charging Taurus in this illustration from the Uranographia of Johann Bode (1801). Orion’s right shoulder is marked by the bright star Betelgeuse, and his left foot by Rigel. A line of three stars forms his belt.

Orion’s Belt, called Drie Konings (Three Kings) or The Belt of Orion, is an asterism within the constellation. It consists of the three bright stars Zeta (Alnitak), Epsilon (Alnilam), and Delta (Mintaka).

The constellation of the Hunter is of great antiquity. It was known to the Sumerians of Mesopotamia as Uru-anna or the Light of Heaven. It was identified with the great Sumerian hero Gilgamesh, who was seen as battling the Bull of Heaven, Gut-anna, which we see as the constellation of Taurus.

The Star in the East and Three Kings

Hayk (Armenian: Հայկ) or Hayg, also known as Haik Nahapet (Հայկ Նահապետ, Hayk the Tribal Chief) is the legendary patriarch and founder of the Armenian nation. He was identified with the Sun-god Orion. His story is told in the History of Armenia attributed to the Armenian historian Moses of Chorene (410 to 490).

–

Orion Constellation – Constellation Guide

Orion is the most splendid of constellations, befitting a character who was in legend the tallest and most handsome of men. His right arm and left foot are marked by the brilliant stars Betelgeuse and Rigel, with a distinctive line of three stars forming his belt. ‘No other constellation more accurately represents the figure of a man’, says Germanicus Caesar.

Manilius calls it ‘golden Orion’ and ‘the mightiest of constellations’, and exaggerates its brilliance by saying that, when Orion rises, ‘night feigns the brightness of day and folds its dusky wings’. Manilius describes Orion as ‘stretching his arms over a vast expanse of sky and rising to the stars with no less huge a stride’.

In fact, Orion is not an exceptionally large constellation, ranking only 26th in size (smaller, for instance, than Perseus according to the modern constellation boundaries), but the brilliance of its stars gives it the illusion of being much larger.

Orion is a prominent constellation located on the celestial equator and visible throughout the world. It is one of the most conspicuous and recognizable constellations in the night sky. Orion is also one of the most ancient constellations, being among the few star groups known to the earliest Greek writers such as Homer and Hesiod.

The distinctive pattern of Orion has been recognized in numerous cultures around the world, and many myths have been associated with it. It has also been used as a symbol in the modern world. It was named after Orion, a hunter in Greek mythology. Even in the space age, Orion remains one of the few star patterns that non-astronomers can recognize.

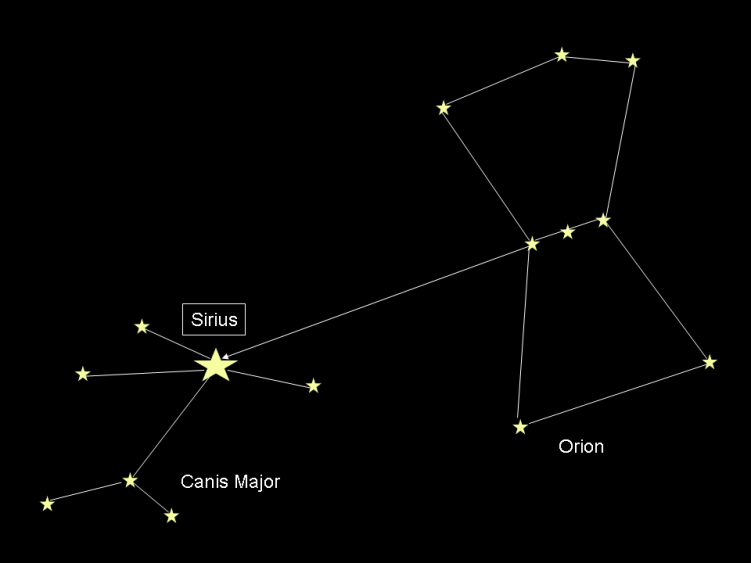

Orion is very useful as an aid to locating other stars. By extending the line of the Belt southwestward, Sirius (α CMa) can be found; northeastward, Aldebaran (α Tau). A line westward across the two shoulders indicates the direction of Procyon (α CMi). A line from Rigel through Betelgeuse points to Castor and Pollux (α Gem and β Gem).

Additionally, Rigel is part of the Winter Circle. Sirius and Procyon, which may be located from Orion by following imaginary lines (see map), also are points in both the Winter Triangle and the Circle.

Its brightest stars are Rigel (Beta Orionis) and Betelgeuse (Alpha Orionis), a blue-white and a red supergiant respectively. Many of the other brighter stars in the constellation are hot, blue supergiant stars. The three stars in the middle of the constellation form an asterism known as Orion’s belt. The Orion Nebula is located south of Orion’s belt.

Orion’s Belt or the Belt of Orion is an asterism in the constellation Orion. It consists of the three bright stars Alnitak, Alnilam and Mintaka. Looking for Orion’s Belt in the night sky is the easiest way to locate the constellation Orion in the sky.

The stars are more or less evenly spaced in a straight line, and so can be visualized as the belt of the hunter’s clothing. In the Northern hemisphere, they are best visible in the early night sky during the winter, in particular the month of January at around 9.00 pm.

The same three stars are known in Spain, Portugal and South America as “Las Tres Marías”. They also mark the northern night sky when the sun is at its lowest point, and were a clear marker for ancient timekeeping.

In the Philippines and Puerto Rico they are called the Los Tres Reyes Magos. The stars start appearing around the holiday of Epiphany, when the Biblical Magi visited the baby Jesus, which falls on January 6.

Richard Hinckley Allen lists many folk names for the Belt of Orion. The English ones include: Our Lady’s Wand; the Magi; the Three Kings; the Three Marys; or simply the Three Stars.

The Armenians identified their forefather Hayk, or Hayg, also known as Haik Nahapet (Hayk the Tribal Chief), the legendary patriarch and founder of the Armenian nation, with the Sun-god Orion. Haykis His story is told in the History of Armenia attributed to the Armenian historian Moses of Chorene (410 to 490).

Hayk is also the name of the Orion constellation in the Armenian translation of the Bible. The legendary archer and forefather of the Armenian people, Haik slew the Titan Bel. In ancient Aram, the constellation was known as Nephîlā′, the Nephilim may have been Orion’s descendants. Neptune (Poseidon).

Khaldi was a warrior god whom the kings of Urartu would pray to for victories in battle. The temples dedicated to Khaldi were adorned with weapons, such as swords, spears, bow and arrows, and shields hung off the walls and were sometimes known as ‘the house of weapons’.

Of all the gods of Ararat (Urartu) panthenon, the most inscriptions are dedicated to him. His wife was the goddess Arubani, the Urartian’s goddess of fertility and art. He is portrayed as a man with or without a beard, standing on a lion.

However, the constellation originated with the Sumerians, who saw in it their great hero Gilgamesh fighting the Bull of Heaven. The Sumerian name for Orion was URU AN-NA, meaning light of heaven. ARA in Armenian means sun. Taurus was Gu-gal-anna, (lit. “The Great Bull of Heaven” < Sumerian gu “bull”, gal “great”, an “heaven”, -a “of”). The Babylonian star catalogues of the Late Bronze Age name Orion MULSIPA.ZI.AN.NA, “The Heavenly Shepherd” or “True Shepherd of Anu” – Anu being the chief god of the heavenly realms.

The Babylonian constellation was sacred to Papshukal and Ninshubur, both minor gods fulfilling the role of ‘messenger to the gods’. Papshukal was closely associated with the figure of a walking bird on Babylonian boundary stones, and on the star map the figure of the Rooster was located below and behind the figure of the True Shepherd – both constellations represent the herald of the gods, in his bird and human forms respectively.

The stars of Orion were associated with Osiris, the sun-god of rebirth and the afterlife, by the ancient Egyptians. In ancient Egypt, the constellation of Orion represented Osiris, who, after being killed by his evil brother Set, was revived by his wife Isis to live immortal among the stars.

Through the hope of new life after death, Osiris began to be associated with the cycles observed in nature, in particular vegetation and the annual flooding of the Nile, through his links with Orion and Sirius at the start of the new year. Osiris was widely worshipped as Lord of the Dead until the suppression of the Egyptian religion during the Christian era.

Orion has also been identified with the Egyptian Pharaoh of the Fifth Dynasty called Unas who, according to the Pyramid Texts, became great by eating the flesh of his mortal enemies and then slaying and devouring the gods themselves. This was based on a belief in contagious magic whereby consuming the flesh of great people would bring inheritance of their power.

After devouring the gods and absorbing their spirits and powers, Unas journeys through the day and night sky to become the star Sahu, or Orion. The Pyramid Texts also show that the dead Pharaoh was identified with the god Osiris, whose form in the stars was often said to be the constellation Orion.

Orion’s current name derives from Greek mythology, in which Orion was a gigantic, supernaturally strong hunter of ancient times, born to Euryale, a nymph, and Poseidon (Neptune), god of the sea in the Greco-Roman tradition.

In one story Orion fell in love with the Pleiades; some say that it was the mother of the Pleiades whom Orion loved. Her name was Pleione. The story has it that Zeus snatched up the Seven Sisters who are the Pleiades and placed them in the sky where Orion still pursues them.

Myth has it that Orion was killed by the sting of a Scorpion. The Scorpion is identified with the constellation of Scorpius, halfway around the sky from Orion. Some say that the Scorpion was sent by the Gaia the Goddess of the Earth who sent the Scorpion to kill Orion, because Orion had dared to say that he would kill every animal on the planet.

Others say that Orion had attempted to force himself on Artemis, the Goddess of the Hunt, and that it was because of his unwanted attentions that Artemis sent the Scorpion after him. The angry goddess tried to dispatch Orion with a scorpion. But as the Scorpion rises in the east, Orion sets, indicating the victory of the Scorpion over the Hunter. This is given as the reason that the constellations of Scorpius and Orion are never in the sky at the same time.

After being poisoned by the Scorpion, Orion was resurrected with an antidote by Asclepius the God of Healing, whom we see in the sky as Ophiuchus, the Serpent Wrestler. Asclepius himself was killed by a thunderbolt of Zeus, because he was restoring too many souls to life so that the Underworld, the realm of the dead, was becoming depopulated.

This is said to be the reason that the constellation of Ophiuchus stands midway between the Scorpion and the Hunter in the sky. The constellation is mentioned in Horace’s Odes (Ode 3.27.18), Homer’s Odyssey (Book 5, line 283) and Iliad, and Virgil’s Aeneid (Book 1, line 535). Thanks to Asclepius, we see Orion later in the year rising as the Scorpion sets, crushed by the heel of Ophiuchus.

There is another very different story of the death of Orion holds that Orion was in fact betrothed to Artemis, but Apollo, the brother of Artemis was opposed to the wedding. Artemis was very proud of her skill as an archer. So one day Apollo challenged Artemis to put an arrow through a small dark object that could be seen far off in the distance bobbing above the waves of the sea. Artemis easily pierced the object with a single shot and was horrified that she had killed her husband-to-be Orion. Filled with grief, she placed him among the stars.

The Bible mentions Orion three times, naming it “Kesil” (literally – fool). Though, this name perhaps is etymologically connected with “Kislev”, the name for the ninth month of the Hebrew calendar (i.e. November–December), which, in turn, may derive from the Hebrew root K-S-L as in the words “kesel, kisla” (hope, positiveness), i.e. hope for winter rains.): Job 9:9 (“He is the maker of the Bear and Orion”), Job 38:31 (“Can you loosen Orion`s belt?”), and Amos 5:8 (“He who made the Pleiades and Orion”).

In medieval Muslim astronomy, Orion was known as al-jabbar, “the giant”. Orion’s sixth brightest star, Saiph, is named from the Arabic, saif al-jabbar, meaning “sword of the giant”.

Sirius

Ara the Beautiful, the god of spring, flora, agriculture, sowing and water, is associated with Osiris, Vishnu and Dionysus, as the symbol of new life. Aralez, or Aralezner, the oldest gods in the Armenian pantheon, are dog-like creatures with powers to resuscitate fallen warriors and resurrect the dead by licking wounds clean.

Sirius is the brightest star in the night sky. With a visual apparent magnitude of −1.46, it is almost twice as bright as Canopus, the next brightest star. The star has the Bayer designation Alpha Canis Majoris (α CMa).

The name “Sirius” is derived from the Ancient Greek Seirios (“glowing” or “scorcher”), although the Greek word itself may have been imported from elsewhere before the Archaic period, one authority suggesting a link with the Egyptian god Osiris.

What the naked eye perceives as a single star is actually a binary star system, consisting of a white main-sequence star of spectral type A1V, termed Sirius A, and a faint white dwarf companion of spectral type DA2, called Sirius B. The distance separating Sirius A from its companion varies between 8.2 and 31.5 AU.

Sirius appears bright because of both its intrinsic luminosity and its proximity to Earth. At a distance of 2.6 parsecs (8.6 ly), as determined by the Hipparcos astrometry satellite, the Sirius system is one of Earth’s near neighbors; for Northern-hemisphere observers between 30 degrees and 73 degrees of latitude (including almost all of Europe and North America), it is the closest star (after the Sun) that can be seen with the naked eye.

Sirius is gradually moving closer to the Solar System, so it will slightly increase in brightness over the next 60,000 years. After that time its distance will begin to recede, but it will continue to be the brightest star in the Earth’s sky for the next 210,000 years.

Sirius A is about twice as massive as the Sun and has an absolute visual magnitude of 1.42. It is 25 times more luminous than the Sun but has a significantly lower luminosity than other bright stars such as Canopus or Rigel.

The system is between 200 and 300 million years old. It was originally composed of two bright bluish stars. The more massive of these, Sirius B, consumed its resources and became a red giant before shedding its outer layers and collapsing into its current state as a white dwarf around 120 million years ago.

Many cultures have historically attached special significance to Sirius, particularly in relation to dogs. Indeed, it is often colloquially called the “Dog Star”, reflecting its prominence as the brightest star in its constellation, Canis Major, the “Great Dog” constellation.

It was classically depicted as Orion’s dog. The Ancient Greeks thought that Sirius’s emanations could affect dogs adversely, making them behave abnormally during the “dog days,” the hottest days of the summer. The Romans knew these days as dies caniculares, and the star Sirius was called Canicula, “little dog.”

The excessive panting of dogs in hot weather was thought to place them at risk of desiccation and disease. In extreme cases, a foaming dog might have rabies, which could infect and kill humans whom they had bitten.

The heliacal rising of Sirius marked the flooding of the Nile in Ancient Egypt and the “dog days” of summer for the ancient Greeks, while to the Polynesians it marked winter and was an important star for navigation around the Pacific Ocean.

In Sanskrit it is known as Mrgavyadha “deer hunter”, or Lubdhaka “hunter”. As Mrgavyadha, the star represents Rudra (Shiva). The star is referred as Makarajyoti in Malayalam and has religious significance to the pilgrim center Sabarimala. In Scandinavia, the star has been known as Lokabrenna (“burning done by Loki”, or “Loki’s torch”).

In Iranian mythology, especially in Persian mythology and in Zoroastrianism, the ancient religion of Persia, Sirius appears as Tishtrya and is revered as the rain-maker divinity (Tishtar of New Persian poetry).

Tishtrya (Tištrya) is the Avestan language name of an Zoroastrian benevolent divinity associated with life-bringing rainfall and fertility. Tishtrya is Tir in Middle- and Modern Persian. As has been judged from the archaic context in which Tishtrya appears in the texts of the Avesta, the divinity/concept is almost certainly of Indo-Iranian origin.

During the Achaemenid period, Tishtrya was conflated with Semitic Nabu-Tiri, and thus came to be associated with the Dog Star, Sirius. The Tiregan festival, previously associated with Tiri (a reconstructed name), was likewise transferred to Tishtrya. During the Hellenic period, Tishtrya came to be associated with Pythian Apollo, patron of Delphi, and thus a divinity of oracles.

Due to the concept of the yazatas, powers which are “worthy of worship”, Tishtrya is a divinity of rain and fertility and an antagonist of apaosha, the demon of drought. In this struggle, Tishtrya is beautifully depicted as a white horse.

Beside passages in the sacred texts of the Avesta, the Avestan language Tishtrya followed by the version Tir in Middle and New Persian is also depicted in the Persian epic Shahnameh of Ferdowsi.

The Armenian god Tir, or Tiur, god of wisdom, culture, science and studies, he also was an interpreter of dreams, was the messenger of the gods and was associated with Apollo. Tir’s temple was located near Artashat.

In Chinese astronomy the star is known as the star of the “celestial wolf”. Farther afield, many nations among the indigenous peoples of North America also associated Sirius with canines; the Seri and Tohono O’odham of the southwest note the star as a dog that follows mountain sheep, while the Blackfoot called it “Dog-face”.

The Cherokee paired Sirius with Antares as a dog-star guardian of either end of the “Path of Souls”. The Pawnee of Nebraska had several associations; the Wolf (Skidi) tribe knew it as the “Wolf Star”, while other branches knew it as the “Coyote Star”. Further north, the Alaskan Inuit of the Bering Strait called it “Moon Dog”.

Several cultures also associated the star with a bow and arrows. The Ancient Chinese visualized a large bow and arrow across the southern sky, formed by the constellations of Puppis and Canis Major. In this, the arrow tip is pointed at the wolf Sirius.

A similar association is depicted at the Temple of Hathor in Dendera, where the goddess Satet has drawn her arrow at Hathor (Sirius). Known as “Tir”, the star was portrayed as the arrow itself in later Persian culture.

Dying-and-rising god

Coming was announced by Three Wise Men: the three stars Mintaka, Anilam, and Alnitak in the belt of Orion, which point directly to Osiris’ star in the east, Sirius, significator of his birth.

The ‘Dying God’ is a symbolic mythological representation of ‘death and resurrection’. Some of the other historical cultural and mythological figures representing the evolutionary death and resurrection motiff include Tammuz, Osiris, Isis and Horus, Mithras, Attis and Cbele, Adonis and Venus, the Cabiri, Dionysos, Jesus and Maria, and many another representative of the active and passive ‘Powers of Nature’.

In comparative mythology, the related motifs of a dying god and of a dying-and-rising god (also known as a death-rebirth-deity) have appeared in diverse cultures.

In the more commonly accepted motif of a dying god, the deity goes away and does not return. The less than widely accepted motif of a dying-and-rising god refers to a deity which returns, is resurrected or is reborn, in either a literal or symbolic sense.

Beginning in the 19th century, a number of gods who would fit these motifs were proposed. Male examples include the ancient Near Eastern, Greek, and Norse deities Baal, Melqart, Adonis, Eshmun, Tammuz, Ra the Sun god with its fusion with Osiris/Orion, Jesus, and Dionysus. Female examples include Inanna/Ishtar, Persephone, and Bari.

The methods of death can be diverse, the Norse Baldr mistakenly dies by the arrow of his blind brother, the Aztec Quetzalcoatl sets himself on fire after over-drinking, and the Japanese Izanami dies of a fever. Some gods who die are also seen as either returning or bringing about life in some other form, in many cases associated with a vegetation deity related to a staple.

The very existence of the category “dying-and-rising-god” was debated throughout the 20th century, and the soundness of the category was widely questioned, given that many of the proposed gods did not return in a permanent sense as the same deity.

Tammuz, “faithful or true son”, was the name of a Sumerian god of food and vegetation, also worshiped in the later Mesopotamian states of Akkad, Assyria and Babylonia.

In Babylonia, the month Tammuz was established in honor of the eponymous god Tammuz, who originated as a Sumerian shepherd-god, Dumuzid or Dumuzi, the consort of Inanna and, in his Akkadian form, the parallel consort of Ishtar. The Levantine Adonis (“lord”), who was drawn into the Greek pantheon, was considered by Joseph Campbell among others to be another counterpart of Tammuz, son and consort.

The Aramaic name “Tammuz” seems to have been derived from the Akkadian form Tammuzi, based on early Sumerian Damu-zid.[citation needed] The later standard Sumerian form, Dumu-zid, in turn became Dumuzi in Akkadian. Tamuzi also is Dumuzid or Dumuzi.

Beginning with the summer solstice came a time of mourning in the Ancient Near East, as in the Aegean: the Babylonians marked the decline in daylight hours and the onset of killing summer heat and drought with a six-day “funeral” for the god. Recent discoveries reconfirm him as an annual life-death-rebirth deity: tablets discovered in 1963 show that Dumuzi was in fact consigned to the Underworld himself, in order to secure Inanna’s release,[2] though the recovered final line reveals that he is to revive for six months of each year (see below).

In cult practice, the dead Tammuz was widely mourned in the Ancient Near East. Locations associated in antiquity with the site of his death include both Harran and Byblos, among others.

According to some scholars, the Church of the Nativity in Bethlehem is built over a cave that was originally a shrine to Adonis-Tammuz.

The Greek Adōnis was a borrowing from the Semitic word adon, “lord”, which is related to Adonai, one of the names used to refer to the God in the Hebrew Bible and still used in Judaism to the present day. Syrian Adonis is Gauas or Aos, to Egyptian Osiris, to the Semitic Tammuz and Baal Hadad, to the Etruscan Atunis and the Phrygian Attis, all of whom are deities of rebirth and vegetation.

Adonis, in Greek mythology, is the god of beauty and desire, and is a central figure in various mystery religions. His religion belonged to women: the dying of Adonis was fully developed in the circle of young girls around the poet Sappho from the island of Lesbos, about 600 BC, as revealed in a fragment of Sappho’s surviving poetry.

Adonis is one of the most complex figures in classical times. He has had multiple roles, and there has been much scholarship over the centuries concerning his meaning and purpose in Greek religious beliefs. He is an annually-renewed, ever-youthful vegetation god, a life-death-rebirth deity whose nature is tied to the calendar. His name is often applied in modern times to handsome youths, of whom he is the archetype. Adonis is often referred to as the mortal god of Beauty.

The Church Father Jerome, who died in Bethlehem in 420, reports in addition that the holy cave was at one point consecrated by the heathen to the worship of Adonis, and a pleasant sacred grove planted before it, to wipe out the memory of Jesus. Modern mythologists, however, reverse the supposition, insisting that the cult of Adonis-Tammuz originated the shrine and that it was the Christians who took it over, substituting the worship of their own God.

Adonis was certainly based in large part on Tammuz. His name is Semitic, a variation on the word “adon” meaning “lord”. Yet there is no trace of a Semitic deity directly connected with Adonis, and no trace in Semitic languages of any specific mythemes connected with his Greek myth; both Greek and Near Eastern scholars have questioned the connection (Burkert, p 177 note 6 bibliography). The connection in practice is with Adonis’ Mesopotamian counterpart, Tammuz:

“Women sit by the gate weeping for Tammuz, or they offer incense to Baal on roof-tops and plant pleasant plants. These are the very features of the Adonis legend: which is celebrated on flat roof-tops on which sherds sown with quickly germinating green salading are placed, Adonis gardens… the climax is loud lamentation for the dead god.” – Burkert, p. 177.

When the legend of Adonis was incorporated into Greek culture is debated. Walter Burkert questions whether Adonis had not from the very beginning come to Greece with Aphrodite. “In Greece” Burkert concludes, “the special function of the Adonis legend is as an opportunity for the unbridled expression of emotion in the strictly circumscribed life of women, in contrast to the rigid order of polis and family with the official women’s festivals in honour of Demeter.”

In comparative mythology, the related motifs of a dying god and of a dying-and-rising god (also known as a death-rebirth-deity) have appeared in diverse cultures. In the more commonly accepted motif of a dying god, the deity goes away and does not return. The less than widely accepted motif of a dying-and-rising god refers to a deity which returns, is resurrected or is reborn, in either a literal or symbolic sense.

Beginning in the 19th century, a number of gods who would fit these motifs were proposed. Male examples include the ancient Near Eastern, Greek, and Norse deities Baal, Melqart, Adonis, Eshmun, Tammuz, Ra the Sun god with its fusion with Osiris/Orion, Jesus, and Dionysus. Female examples include Inanna/Ishtar, Persephone, and Bari.

Ara the Beautiful (also Ara the Handsome or Ara the Fair; Armenian: Արա Գեղեցիկ Ara Geghetsik) is a legendary Armenian hero. He is notable in Armenian literature for the popular legend in which he was so handsome that the Assyrian queen Semiramis waged war against Armenia just to get him.

Is an Armenian mythological name, the name of God of spring, flora, harvest; later – God of war, strength. Some scientists find analogy between Arm god Ara and Greek Ares ( as dying and rising from the dead gods).

Religions of the ancient Near East

The Bull

In the sky, Orion is depicted facing the snorting charge of neighbouring Taurus the Bull. The oldest known zodiac was measured from the eye of the Bull, the great ‘red giant’, Aldebaran, ‘The Watcher in the East’, which was also the star of the archangel Michael. Taurus, with its ‘V’ shaped face of stars, lies to the north of the Great Hunter, Orion on the zodiac band.

Gilgamesh was the Sumerian equivalent of Heracles, which brings us to another puzzle. Being the greatest hero of Greek mythology, Heracles deserves a magnificent constellation such as this one, but in fact is consigned to a much more obscure area of sky.

So is Orion really Heracles in another guise? It might seem so, for one of the labours of Heracles was to catch the Cretan bull, which would fit the Orion – Taurus conflict in the sky, while the myth of Orion makes no reference to such a combat.

Ptolemy described him with club and lion’s pelt, both familiar attributes of Heracles, and he is shown this way on old star maps. Despite these facts, no mythologist hints at a connection between this constellation and Heracles.

Taurus, the bull, is one of the most ancient symbols of fertility and power and was sacred to the Great Goddess. The white ‘Bull of Heaven’ was created at the behest of Ishtar, the Babylonian Venus, in order to destroy Gilgamesh, the world’s first hero, who had spurned her favours. He accused her of destroying all her lovers, which included lions and horses.

After Gilgamesh upsets the goddess Ishtar, she convinces her father Anu to send the Bull of Heaven to earth to destroy the crops and kill people. However, Gilgamesh and Enkidu kill the Bull of Heaven. The gods are angry that the Bull of Heaven has been killed. As punishment for killing the bull Enkidu falls ill and dies.

In Mesopotamian mythology Gugalanna was a Sumerian deity as well as a constellation known today as Taurus, one of the twelve signs of the Zodiac. Gugalanna was the first husband of the Goddess Ereshkigal, the Goddess of the Realm of the Dead, a gloomy place devoid of light, who was dispatched by Inanna to punish Gilgamesh for his sins.

Gugalanna was sent by the gods to take retribution upon Gilgamesh for rejecting the sexual advances of the goddess Inanna. Gugalanna, whose feet made the earth shake, was slain and dismembered by Gilgamesh and Enkidu.

Inanna, from the heights of the city walls looked down, and Enkidu took the haunches of the bull shaking them at the goddess, threatening he would do the same to her if he could catch her too. For this impiety, Enkidu later dies. It was to share the sorrow with her sister that Inanna later descends to the Underworld.

Aurochs are depicted in many Paleolithic European cave paintings such as those found at Lascaux and Livernon in France. Their life force may have been thought to have magical qualities, for early carvings of the aurochs have also been found.

The impressive and dangerous aurochs survived into the Iron Age in Anatolia and the Near East and was worshipped throughout that area as a sacred animal; the earliest survivals of a bull cult are at neolithic Çatalhöyük.

We cannot recreate a specific context for the bull skulls with horns (bucrania) preserved in an 8th millennium BCE sanctuary at Çatalhöyük in eastern Anatolia. The sacred bull of the Hattians, whose elaborate standards were found at Alaca Höyük alongside those of the sacred stag, survived in the Hurrian and Hittite mythologies as Seri and Hurri (Day and Night)—the bulls who carried the weather god Teshub on their backs or in his chariot, and grazed on the ruins of cities.

The bull was seen in the constellation Taurus by the Chalcolithic and had marked the new year at springtide by the Bronze Age, for 4000–1700 BCE.

“Between the period of the earliest female figurines circa 4500B.C…a span of a thousand years elapsed, during which the archaeological signs constantly increase of a cult of the tilled earth fertilised by that noblest and most powerful beast of the recently developed holy barnyard, the bull – who not only sired the milk yielding cows, but also drew the plow, which in that early period simultaneously broke and seeded the earth.

Moreover by analogy, the horned moon, lord of the rhythm of the womb and of the rains and dews, was equated with the bull; so that the animal became a cosmological symbol, uniting the fields and the laws of sky and earth.”

Taurus was the constellation of the Northern Hemisphere Spring Equinox from about 3,200 BC. It marked the start of the agricultural year with the New Year Akitu festival (from á-ki-ti-še-gur10-ku5, = sowing of the barley), an important date in Mespotamian religion. The “death” of Gugalanna, represents the obscuring disappearance of this constellation as a result of the light of the sun, with whom Gilgamesh was identified.

In the time in which this myth was composed, the New Year Festival, or Akitu, at the Spring Equinox, due to the Precession of the Equinoxes did not occur in Aries, but in Taurus. At this time of the year, Taurus would have disappeared as it was obscured by the sun.

In Mesopotamian mythology, Gugalanna (lit. “The Great Bull of Heaven” < Sumerian gu “bull”, gal “great”, an “heaven”, -a “of”) was a Sumerian deity as well as a constellation known today as Taurus, one of the twelve signs of the Zodiac. The “death” of Gugalanna represents the obscuring disappearance of this constellation as a result of the light of the sun, with whom Gilgamesh was identified.

The Sumerian Epic of Gilgamesh depicts the killing by Gilgamesh and Enkidu of the Bull of Heaven, Gugalana, first husband of Ereshkigal, as an act of defiance of the gods. From the earliest times, the bull was lunar in Mesopotamia (its horns representing the crescent moon).

Gugalanna was the first husband of the Goddess Ereshkigal, the Goddess of the Realm of the Dead, a gloomy place devoid of light, who was dispatched by Inanna to punish Gilgamesh for his sins.

Gugalanna was sent by the gods to take retribution upon Gilgamesh for rejecting the sexual advances of the goddess Inanna. Gugalanna, whose feet made the earth shake, was slain and dismembered by Gilgamesh and Enkidu.

Inanna, from the heights of the city walls looked down, and Enkidu took the haunches of the bull shaking them at the goddess, threatening he would do the same to her if he could catch her too. For this impiety, Enkidu later dies. It was to share the sorrow with her sister that Inanna later descends to the Underworld.

Marduk is the “bull of Utu”. Shiva’s steed is Nandi, the Bull. The sacred bull survives in the constellation Taurus. The bull, whether lunar as in Mesopotamia or solar as in India, is the subject of various other cultural and religious incarnations, as well as modern mentions in new age cultures.

In Egypt, the bull was worshiped as Apis, the embodiment of Ptah and later of Osiris. A long series of ritually perfect bulls were identified by the god’s priests, housed in the temple for their lifetime, then embalmed and encased in a giant sarcophagus.

A long sequence of monolithic stone sarcophagi were housed in the Serapeum, and were rediscovered by Auguste Mariette at Saqqara in 1851. The bull was also worshipped as Mnewer, the embodiment of Atum-Ra, in Heliopolis. Ka in Egyptian is both a religious concept of life-force/power and the word for bull.

Among the Egyptians’ and Hebrews’ neighbors in the Ancient Near East and in the Aegean, the Aurochs, the wild bull, was widely worshipped, often as the Lunar Bull and as the creature of El.

The Bull was a central theme in the Minoan civilization, with bull heads and bull horns used as symbols in the Knossos palace. Minoan frescos and ceramics depict the bull-leaping ritual in which participants of both sexes vaulted over bulls by grasping their horns. See also “Minotaur and The Bull of Crete” for a later incarnation to the Minoan Bull.

In Cyprus, bull masks made from real skulls were worn in rites. Bull-masked terracotta figurines and Neolithic bull-horned stone altars have been found in Cyprus.

Nandi appears in the Hindu mythology as the primary vehicle and the principal gana (follower) of Shiva. Bulls also appear on the Indus Valley seals from Pakistan as well, but most scholars agree that the horned bull on these seals is not identical to Nandi.

The worship of the Sacred Bull throughout the ancient world is most familiar to the Western world in the Biblical episode of the idol of the Golden Calf. The Golden Calf after being made by the Hebrew people in the wilderness of Sinai, were rejected and destroyed by Moses and the Hebrew people after Moses’ time upon Mount Sinai (Book of Exodus).

According to the Hebrew Bible, the golden calf was an idol (a cult image) made by Aaron to satisfy the Israelites during Moses’ absence, when he went up to Mount Sinai. In Hebrew, the incident is known as “The Sin of the Calf”. It is first mentioned in Exodus 32:4.

In Egypt, whence according to the Exodus narrative the Hebrews had recently come, the Apis Bull was a comparable object of worship, which some believe the Hebrews were reviving in the wilderness; alternatively, some believe the God of Israel was associated with or pictured as a calf/bull deity through the process of religious assimilation and syncretism.

The Canaanite (and later Carthaginian) deity Moloch was often depicted as a bull. Exodus 32:4 “He took this from their hand, and fashioned it with a graving tool and made it into a molten calf; and they said, ‘This is your god, O Israel, who brought you up from the land of Egypt’.” Nehemiah 9:18 “even when they made an idol shaped like a calf and said, “This is your god who brought you out of Egypt!” They committed terrible blasphemies.”

Calf-idols are referred to later in the Tanakh, such as in the Book of Hosea, which would seem accurate as they were a fixture of near-eastern cultures. King Solomon’s “bronze sea” basin stood on 12 brazen bulls. Young bulls were set as frontier markers at Tel Dan and at Bethel the frontiers of the Kingdom of Israel.

Much later, in Abrahamic traditions, the bull motif became a bull demon or the “horned devil” in contrast and conflict to earlier traditions. The bull is familiar in Judeo-Christian cultures from the Biblical episode wherein an idol of the Golden Calf is made by Aaron and worshipped by the Hebrews in the wilderness of Sinai (Exodus).

The text of the Hebrew Bible can be understood to refer to the idol as representing a separate god, or as representing the God of Israel himself, perhaps through an association or syncretization with Egyptian or Levantine bull gods, rather than a new deity in itself.]

When the heroes of the new Indo-European culture arrived in the Aegean basin, they faced off with the ancient Sacred Bull on many occasions, and always overcame him, in the form of the myths that have survived.

In the Olympian cult, Hera’s epithet Bo-opis is usually translated “ox-eyed” Hera, but the term could just as well apply if the goddess had the head of a cow, and thus the epithet reveals the presence of an earlier, though not necessarily more primitive, iconic view.

Classical Greeks never otherwise referred to Hera simply as the cow, though her priestess Io was so literally a heifer that she was stung by a gadfly, and it was in the form of a heifer that Zeus coupled with her. Zeus took over the earlier roles, and, in the form of a bull that came forth from the sea, abducted the high-born Phoenician Europa and brought her, significantly, to Crete.

Dionysus was another god of resurrection who was strongly linked to the bull. In a cult hymn from Olympia, at a festival for Hera, Dionysus is also invited to come as a bull, “with bull-foot raging.” “Quite frequently he is portrayed with bull horns, and in Kyzikos he has a tauromorphic image,” Walter Burkert relates, and refers also to an archaic myth in which Dionysus is slaughtered as a bull calf and impiously eaten by the Titans.

For the Greeks, the bull was strongly linked to the Bull of Crete: Theseus of Athens had to capture the ancient sacred bull of Marathon (the “Marathonian bull”) before he faced the Bull-man, the Minotaur (Greek for “Bull of Minos”), whom the Greeks imagined as a man with the head of a bull at the center of the labyrinth. Minotaur was fabled to be born of the Queen and a bull, bringing the king to build the labyrinth to hide his family’s shame.

Living in solitude made the boy wild and ferocious, unable to be tamed or beaten. Yet Walter Burkert’s constant warning is, “It is hazardous to project Greek tradition directly into the Bronze age”; only one Minoan image of a bull-headed man has been found, a tiny seal currently held in the Archaeological Museum of Chania.

In the Classical period of Greece, the bull and other animals identified with deities were separated as their agalma, a kind of heraldic show-piece that concretely signified their numinous presence.

Walter Burkert summarized modern revision of a too-facile and blurred identification of a god that was identical to his sacrificial victim, which had created suggestive analogies with the Christian Eucharist for an earlier generation of mythographers:

The concept of the theriomorphic god and especially of the bull god, however, may all too easily efface the very important distinctions between a god named, described, represented, and worshipped in animal form, a real animal worshipped as a god, animal symbols and animal maskes used in the cult, and finally the consecrated animal destined for sacrifice. Animal worship of the kind found in the Egyptian Apis cult is unknown in Greece. (“Greek Religion,” 1985).

Bull used as an heraldic crest, here for the Fane family, Earls of Westmorland. (Great Britain, this example 18th or 19th century, but inherited early 17th century from a much earlier use of the idiom by the Neville family).

The bull is one of the animals associated with the late Hellenistic and Roman syncretic cult of Mithras, in which the killing of the astral bull, the tauroctony, was as central in the cult as the Crucifixion was to contemporary Christians. The tauroctony was represented in every Mithraeum (compare the very similar Enkidu tauroctony seal).

The tauroctony scene is the cult relief (i.e. the central icon) of the Mithraic Mysteries. It depicts Mithras killing a bull, hence the name ‘tauroctony’, given to the scene in modern times possibly after the Greek ταυροκτόνος (tauroktonos) “slaughtering bulls”, which derives from (tauros) “bull” + (ktonos) “murder”, from (kteinō), “I kill, slay”.

Remnants of Mithraic ritual survive as the bullfighting in Iberia and southern France, where the legend of Saint Saturninus (or Sernin) of Toulouse and his protégé in Pamplona, Saint Fermin, at least, are inseparably linked to bull-sacrifices by the vivid manner of their martryrdoms, set by Christian hagiography in the 3rd century CE, which was also the century in which Mithraism was most widely practiced.

In some Christian traditions, Nativity scenes are carved or assembled at Christmas time. Many show a bull or an ox near the baby Jesus, lying in a manger. Traditional songs of Christmas often tell of the bull and the donkey warming the infant with their breath. This refers (or, at least, is referred) to the beginning of the book of the prophet Isaiah, where he says: “The ox knoweth his owner, and the ass his master’s crib.” (Isaiah 1:3)

A prominent zoomorphic deity type is the divine bull. Tarvos Trigaranus (“bull with three cranes”) is pictured on reliefs from the cathedral at Trier, Germany, and at Notre-Dame de Paris. In Irish mythology, the Donn Cuailnge (“Brown Bull of Cooley”) plays a central role in the epic Táin Bó Cuailnge (“The Cattle-Raid of Cooley”) which features the hero Cú Chulainn, which were collected in the 7th century CE Lebor na hUidre (“Book of the Dun Cow”).

Pliny the Elder, writing in the first century AD, describes a religious ceremony in Gaul in which white-clad druids climbed a sacred oak, cut down the mistletoe growing on it, sacrificed two white bulls and used the mistletoe to cure infertility.

Leave a comment