Neolithic Age

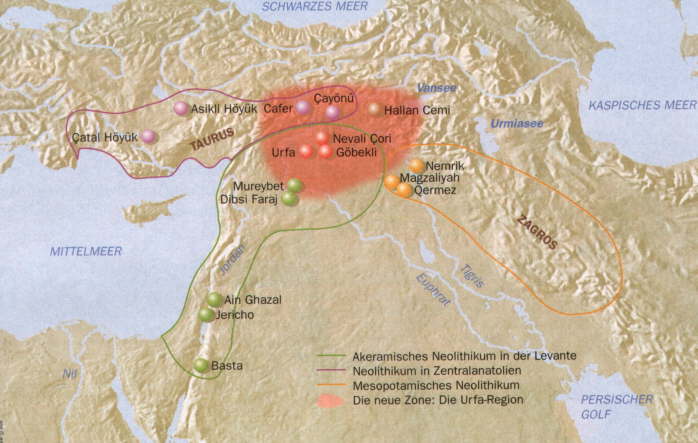

Up to 10 to 15 years ago, the first settled life for human beings in terms of animal feeding and agriculture, the so called “Neolithic Age” society, was being marked in history as B.C. 9500 by the archeology science and this was namely “Jericho” society, today known as “Tell es Sultan” in the “Levant” area.

However, the researches of recent years in the upper “Mezopotomia” region of south-east Anatolia indicated that this marking in History shall be taken backwards and this era qualified by sociology and history as “Neolithic Revolution” for civilization is to begin around the cities of Urfa and Diyarbakır.

The area of “Nevali Çori”, which was excavated between 1963 and 1991, is unfortunately under dam waters today. However, by the help of the excavations held in the area, all the information about “Neolithic Age” obtained up to then have been invaluably enriched and it was revealed that in fact the “Neolithic Age” had taken place in this area between 12.000 and 10.000 BC.

Nevalı Çori was an early Neolithic settlement on the middle Euphrates, in the province of Şanlıurfa (Urfa), eastern Turkey. The site is famous for having revealed some of the world’s most ancient known temples and monumental sculpture. Together with the site of Göbekli Tepe, it has revolutionised scientific understanding of the Eurasian Neolithic.

A stone head discovered at the Neolithic site of Nevalı Çori in Anatolia features what some have interpreted as an early example of a śikhā, perhaps the mark of a priest or shaman. The local limestone was carved into numerous statues and smaller sculptures, including a more than life-sized bare human head with a snake or sikha-like tuft.

The sikha or shikha is a Sanskrit word that refers to a long tuft, or lock of hair left on top or on the back of the shaven head of a male Hindu. Though traditionally all Hindus were required to wear a śikhā, today it is seen mainly among traditional believers like vedic students and scholars, priests, devotional musicians, religious leaders, saints and many traditional families mostly from the brahmin community.

The existence of temple architecture founded on stone with floor tiling gives us important clues about the belief of the man of this era. The sculpture out of stone and the art of “KABARTMA” beautifying this architecture proves the importance of this area.

With its architectural and cultural similarities to “Nevali Çori”, the other significant site in the Harran Plateau, “Göbekli Tepe” which is being excavated since 1995 is another strong evidence of the thesis set forward for the first time by the findings of the former. Initiated by these two sites, as a geographical area where the roots of the civilization are fertilized, south-east Anatolia has become a point of attraction for researchers from all over the world.

When both sites are viewed in terms of sculpture findings, as a surprising result, male figures are in the majority and no evidence related to “Mother Goddess” the irreplacable figure for the Anatolian cultures has been traced. However, Professor Hauptmann set forward his views on this topic that, with the existing evidence, we cannot talk of worship on male Gods within the area.

Portasar – Gobekli Tepe

Göbekli Tepe (“Potbelly Hill”) is a Neolithic hilltop sanctuary erected at the top of a mountain ridge in the Southeastern Anatolia Region of Turkey, some 15 kilometers (9 mi) northeast of the town of Şanlıurfa (formerly Urfa / Edessa).

It is the oldest known human-made religious structure. The site was most likely erected in the 10th millennium BCE and has been under excavation since 1994 by German and Turkish archaeologists.

Together with Nevalı Çori, it has revolutionized understanding of the Eurasian Neolithic. The PPN A settlement has been dated to c. 9000 BCE. There are remains of smaller houses from the PPN B and a few epipalaeolithic finds as well.

Turkey presents Armenian Portasar to the world as a Turkish Stonehenge. “Turkey doesn’t stop distorting the history and misappropriate Armenian cultural heritage”, stated a senior fellow of “Stars & Stones 2010: Oxford University Expedition to Qarahunge, Armenia”.

“Presently, Turkey presents the Armenian religious complex of Portasar as a Turkish Stonehenge,” Vachagan Vahradian, candidate of biological sciences, adviser and chief scientist to the Armenian scientific party of Oxford University’s ‘Stones and Stars’ project, told a news conference in Yerevan. “According to research, Portasar is over 18 thousand years old and is one of the most ancient religious complexes in the world.”

Portasar is a great ritualistic-religious-scientific building, which is situated in the Western Armenia and has 18,500-years-old history. Vachagan Vahradyan, said at today’s meeting with journalists that the Turks ascribe the establishment of Portasar to themselves. According to Carl Schmidt, in the Armenian highland the haven was divided into constellations even 12-18 thousand years ago.

Vachagan Vahradyan says the Portasar was built in the eon of Scorpion. Griffon was painted on the huge building. This one and other resemblances come to prove that Portasar has a lot in common with Karahunj; the builders belonged to the same culture.

The scientist says the existence of such a monument creates basis for casting doubt on the opinion about the knowledge of the old civilization. Turkey organizes a number of exhibitions, representing the monument as a Turkish one before the world. Vachagan Vahradyan says it is necessary to reach arrangements with Turkey and conduct excavations in Portasar.

Jericho

Jericho (Arabic: Arīḥā) is a Palestinian city located near the Jordan River in the West Bank. It is believed to be one of the oldest inhabited cities in the world. It is known in Judeo-Christian tradition as the place of the Israelites’ return from bondage in Egypt, led by Joshua, the successor to Moses.

Jericho is described in the Old Testament as the “City of Palm Trees.” Copious springs in and around the city attracted human habitation for thousands of years. Archaeologists have unearthed the remains of more than 20 successive settlements in Jericho, the first of which dates back 11,000 years (9000 BC), almost to the very beginning of the Holocene epoch of the Earth’s history.

Jericho has evidence of settlement dating back to 9000 BC. During the Younger Dryas period of cold and drought, permanent habitation of any one location was not possible. However, the spring at what would become Jericho was a popular camping ground for Natufian hunter-gatherer groups, who left a scattering of crescent microlith tools behind them. Around 9600 BC the droughts and cold of the Younger Dryas Stadial had come to an end, making it possible for Natufian groups to extend the duration of their stay, eventually leading to year round habitation and permanent settlement.

The first permanent settlement was built near the Ein as-Sultan spring between 10000 and 9000 BC. As the world warmed, a new culture based on agriculture and sedentary dwelling emerged, which archaeologists have termed “Pre-Pottery Neolithic A” (abbreviated as PPNA). PPNA villages are characterized by small circular dwellings, burials of the dead within the floors of buildings, reliance on hunting wild game, the cultivation of wild or domestic cereals, and no use of pottery. At Jericho, circular dwellings were built of clay and straw bricks left to dry in the sun, which were plastered together with a mud mortar. Each house measured about 5 metres across, and was roofed with mud-smeared brush. Hearths were located within and outside the homes.

By about 9400 BC the town had grown to more than 70 modest dwellings. Population estimates have been as high as two to three thousand people, but it has been suggested that these are highly exaggerated by at least tenfold. The most striking aspect of this early town was a massive stone wall over 3.6 metres high, and 1.8 metres wide at the base. Inside this wall was a tower over 3.6 metres high, contained an internal staircase with 22 stone steps. The wall and tower were unprecedented in human history, and would have taken a hundred men more than a hundred days to construct it. The wall may have been a defence against flood water with the tower used for ceremonial purposes.

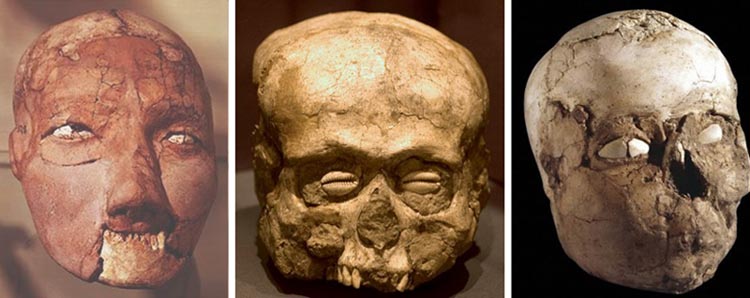

After a few centuries it was abandoned for a second settlement, established in 6800 BC, perhaps by an invading people who absorbed the original inhabitants into their dominant culture. Artifacts dating from this period include ten plastered human skulls, painted so as to reconstitute the individuals’ features. These represent the first example of portraiture in art history, and it is thought that they were kept in people’s homes while the bodies were buried. This was followed by a succession of settlements from 4500 BC onward, the largest being constructed in 2600 BC.

Archaeological evidence indicates that in the latter half of the Middle Bronze Age (circa 1700 BC) the city enjoyed some prosperity, its walls having been strengthened and expanded. According to carbon dating the Canaanite city (Jericho City IV) was destroyed between 1617 and 1530 BC. The site remained uninhabited until the city was refounded in the 9th century BC.

Mesolithic Period

In Old World archaeology, Mesolithic (Greek: mesos “middle”; lithos “stone”) is the period between the Upper Paleolithic and the Neolithic, between the end of the Last Glacial Maximum and the Neolithic Revolution. Mesolithic societies are not seen as very complex, and burials are fairly simple; in contrast, grandiose burial mounds are a mark of the Neolithic.

“Epipaleolithic” is sometimes also used alongside “Mesolithic” for the final end of the Upper Paleolithic immediately followed by the Mesolithic, especially for outside northern Europe, and for the corresponding period in the Levant and Caucasus.

The Epipaleolithic corresponds to the first period of progressive warming after the Last Glacial Maximum (LGM), before the start of the Holocene and the onset of the Neolithic Revolution.

As “Mesolithic” suggests an intermediate period, followed by the Neolithic, some authors prefer the term “Epipaleolithic” to the final period of hunter-gatherer cultures in Europe and Western Asia, who are not succeeded by agricultural traditions, reserving “Mesolithic” for cultures who are clearly succeeded by the Neolithic Revolution, such as the Natufian culture.

Other authors use “Mesolithic” as a generic term for hunter-gatherer cultures after the Last Glacial Maximum, whether they are transitional towards agriculture or not. In addition, terminology appears to differ between archaeological sub-disciplines, with “Mesolithic” being widely used in European archaeology, while “Epipalaeolithic” is more common in Near Eastern archaeology.

The Mesolithic has different time spans in different parts of Eurasia. In Europe it spans roughly 13.000 to 3000 BC, in Southwest Asia (the Epipalaeolithic Near East) roughly 18.000 to 6000 BC. The term is less used of areas further east and not at all beyond Eurasia and North Africa.

The type of culture associated with the Mesolithic varies between areas, but it is associated with a decline in the group hunting of large animals in favour of a broader hunter-gatherer way of life, and the development of more sophisticated and typically smaller lithic tools and weapons than the heavy chipped equivalents typical of the Paleolithic.

Depending on the region, some use of pottery and textiles may be found in sites allocated to the Mesolithic, but generally indications of agriculture are taken as marking transition into the Neolithic.

The more permanent settlements tend to be close to the sea or inland waters offering a good supply of food. Mesolithic societies are not seen as very complex, and burials are fairly simple; in contrast, grandiose burial mounds are a mark of the Neolithic.

The Story Begins

The story begins with Epi-Paleolithic hunters developing a new awareness of their environment and its food resources, both plant and animal. Even before the beginning of the Holocene, circa 8000 BC, some of these groups had started to experiment with the planting of crops – the first steps toward agriculture, and the domestication of some animals. The Neolithic, the period of early farming, had begun.

Distinctive Upper Paleolithic stone industries of blade and burin type used by Homo sapiens for the manufacture of weapons as well as for various household objects in stone, bone, antler, wood and other perishable materials have been recognized in caves or open sites in various regions of the Near East.

The two best known groups are the Levanto-Aurignacian (25,000 – 18,000 BC) in the Levant and the Baradostian (34,000 – 20,000 BC) of the Zagros Mountains of western Iran.

Sites of this period can be divided into base camps, butchering places and intermediate camp sites of hunting bands where numbers were probably limited. Most of the large cave sites served as base camps; smaller shelters may have been used as intermediate sites, but butchering places are often out in the open, though the use of such sites may have varied from season to season. Of permanent occupation there is no trace, and these hunters were evidently migratory throughout the territories they occupied; each group may well have had several sets of caves at their disposal.

Apart from similarities in tool types, there is little evidence to show contract and trade between the various groups at this period. The total number of individuals was probably limited and indeed burials are rare. No evidence for art has yet been discovered.

Some time between 20,000 and 16,000 BC the Upper Paleolithic gave rise to new cultures, collectively called Epi-Paleolithic; Kebaran in the Levant, Belbasi in the Antalya region, and Zarzian in the Zagros mountains. The chief technological invention is that of the microlithic composite tool.

The presence of some microliths in the Baradostian and a tendency towards smaller tools in the late Levanto-Aurignacian strongly suggests that the Epi-Paleolithic cultures were not the result of the arrival of newcomers but represent regional developments from the preceding Upper Paleolithic.

The most characteristic product of the Neolithic was painted pottery, in which was expressed a sense of individuality, artistry and abstraction lacking among many of the earlier, purely artifactual household assemblages [which came before].

In the Neolithic period neither Egypt nor Mesopotamia had yet reached a position of cultural dominance over its neighbours. Urban civilization has predecessors to these two at sites like Jericho or Çatal Höyük, in Palestine and Anatolia, long regarded as backwaters.

It has become abudantly clear that there was no area in the Near East during the Neolithic period that can claim an uninterrupted cultural development; cultures rise and fall.

In Egypt and Sumer in dynastic times, as prehistory faded into dim history in the third millennium BC, new factors were at work: stronger political and economic control which ensured a stability of culture that could and did outlast political strife, foreign invasion, floods and disasters with greater success than had earlier cultures.

Precursors

Mousterian is a name given by archaeologists to a style of predominantly flint tools (or industry) associated primarily with Homo neanderthalensis and dating to the Middle Paleolithic, the middle part of the Old Stone Age.

The culture was named after the type site of Le Moustier, a rock shelter in the Dordogne region of France. Similar flintwork has been found all over unglaciated Europe and also the Near East and North Africa. Handaxes, racloirs and points constitute the industry; sometimes a Levallois technique or another prepared-core technique was employed in making the flint flakes.

Mousterian tools that have been found in Europe were made by Neanderthals and date from between 300,000 BP and 30,000 BP (from Layer 2A dated 330 ± 5 ka, (OIS) 9 at Pradayrol, France). In Northern Africa and the Near East they were also produced by anatomically modern humans. In the Levant for example, assemblages produced by Neanderthals are indistinguishable from those produced by Qafzeh type modern humans.

It may be an example of acculturation of modern humans by Neanderthals because the culture after 130,000 years reached the Levant from Europe (the first Mousterian industry appears there 200,000 BP) and the modern Qafzeh type humans appear in the Levant another 100,000 years later.

Possible variants are Denticulate , Charentian (Ferrassie & Quina) named after the Charente region. Typical and the Acheulean Tradition (MTA) – Type-A and Type-B. The Industry was superseded by the Châtelperronian during 35,000-29,000 BP.

The Emirian culture represents the transition between the Middle Paleolithic and the Upper Paleolithic in the Levant (Syria, Lebanon, Palestine). It apparently developed from the local Mousterian without rupture, keeping numerous elements of the Levalloise-Mousterian, together with the locally typical (but not frequent) point known as Emireh point. There are also numerous stone blade tools, including some curved knives similar to those found in the Chatelperronian culture of Western Europe.

The Emirian eventually evolved into the Upper Paleolithic Antelian culture in the Levant (Syria, Lebanon, Palestine), still of Levalloise tradition but with some Aurignacian influences. The most important innovation in this period is the incorporation of some typical elements of Aurignacian, like some types of burins and narrow blade points that resemble the European type of Font-Yves.

North Africa

The Halfan culture (24,000–17,000 BC) flourished between 18,000 and 15,000 BC in Nubia and Egypt. One Halfan site dates to before 24,000 BC. They lived on a diet of large herd animals and the Khormusan tradition of fishing. Although there are only a few Halfan sites and they are small in size, there is a greater concentration of artifacts, indicating that this was not a people bound to seasonal wandering, but one that had settled, at least for a time.

The Halfan is seen as the parent culture of the Ibero-Maurusian industry which spread across the Sahara and into Spain. Sometimes seen as a proto-Afro-Asiatic culture, this group is derived from the Nile River valley culture known as Halfan, dating to about 17,000 BC.

The Halfan culture was derived in turn from the Khormusan, which depended on specialized hunting, fishing, and collecting techniques for survival. The material remains of this culture are primarily stone tools, flakes, and a multitude of rock paintings. The end of the Khormusan came around 16,000 BC and was concurrent with the development of other cultures in the region, including the Gemaian.

The Iberomaurusian culture is a backed bladelet industry found throughout the Maghreb. The industry was originally described in 1909 by the French scholar Pallary, at the site of Abri Mouillah. Other names for the industry have included “Mouillian” and “Oranian”.

Recent fieldwork indicates that the culture existed in the region from around the timing of the Last Glacial Maximum (LGM), at 20,000 BP, until the Younger Dryas. The culture is succeeded by the Capsian, which was originally thought to have expanded into the Maghreb from the Near East, although later studies have indicated that the Iberomaurusian were the progenitors of the Capsian.

The Capsian culture (named after the town of Gafsa in Tunisia) was a Mesolithic culture of the Maghreb, which lasted from about 10,000 to 6,000 BCE. It was concentrated mainly in modern Tunisia, and Algeria, with some sites attested in southern Spain to Sicily.

It is traditionally divided into two horizons, the Capsien typique (Typical Capsian) and the Capsien supérieur (Upper Capsian) which are sometimes found in chronostratigraphic sequence. They represent variants of one tradition, the differences between them being both typological and technological.

During this period, the environment of the Maghreb was open savanna, much like modern East Africa, with Mediterranean forests at higher altitudes. The Capsian diet included a wide variety of animals, ranging from aurochs and hartebeest to hares and snails; there is little evidence concerning plants eaten. During the succeeding Neolithic of Capsian Tradition, there is evidence from one site, for domesticated, probably imported, ovicaprids.

Anatomically, Capsian populations were modern Homo sapiens, traditionally classed into two “racial” types: Proto-Mediterranean and Mechta-Afalou on the basis of cranial morphology. Some have argued that they were immigrants from the east, whereas others argue for population continuity based on physical skeletal characteristics and other criteria, et cetera.

Given its widespread occurrence in the Sahara, the Capsian culture is identified by some historical linguists as a possible ancestor of the speakers of modern Afroasiatic languages of North Africa which includes the Berber languages in North Africa.

Nothing is known about Capsian religion, but their burial methods suggest a belief in an afterlife. Decorative art is widely found at their sites, including figurative and abstract rock art, and ocher is found coloring both tools and corpses. Ostrich eggshells were used to make beads and containers; seashells were used for necklaces. The Ibero-Maurusian practice of evulsion of the central incisors continued sporadically, but became rarer.

The Eburran industry which dates between 13,000 and 9,000 BCE in East Africa, was formerly known as the “Kenya Capsian” due to similarities in the stone blade shapes.

The Kebarian culture

The Kebaran or Kebarian culture was an archaeological culture in the eastern Mediterranean area (c. 18,000 to 10,000 BC), named after its type site, Kebara Cave south of Haifa. It is preceded by the Athlitian phase of the Antelian and followed by the proto-agrarian Natufian culture of the Epipalaeolithic.

The appearance of the Kebarian culture, of microlithic type implies a significant rupture in the cultural continuity of Levantine Upper Paleolithic. The Kebaran is the last Upper Paleolithic phase of the Levant (Syria, Jordan, Lebanon, Palestine). The Kebarans were characterized by small, geometric microliths, and were thought to lack the specialized grinders and pounders found in later Near Eastern cultures.

The Kebaran were a highly mobile nomadic population, composed of hunters and gatherers in the Levant and Sinai areas who utilized microlithic tools. It is characterised by the earliest collecting of wild cereals, known due to the uncovering of grain grinding tools. It was the first step towards the Neolithic Revolution.

The Kebaran people are believed to have practiced dispersal to upland environments in the summer, and aggregation in caves and rockshelters near lowland lakes in the winter. This diversity of environments may be the reason for the variety of tools found in their toolkits.

Situated in the Terminal Pleistocene, the Kebaran is classified as an Epipalaeolithic society. They are generally thought to have been ancestral to the later Natufian culture that occupied much of the same range.

The Natufian culture

The term “Natufian” was coined by Dorothy Garrod who studied the Shuqba cave in Wadi an-Natuf, in the western Judean Mountains, about halfway between Tel Aviv and Ramallah. Radiocarbon dating places this culture from the terminal Pleistocene to the very beginning of the Holocene, from 12,500 to 9,500 BC.

The Natufian culture was an Epipaleolithic culture that existed from 13,000 to 9,800 years ago in the Levant, a region in the Eastern Mediterranean. The period is commonly split into two subperiods: Early Natufian (12,500–10,800 BC) and Late Natufian (10,800–9500 BC). The Late Natufian most likely occurred in tandem with the Younger Dryas (10,800 to 9500 BC).

The Natufian culture was unusual in that it was sedentary, or semi-sedentary, before the introduction of agriculture. The Natufian communities are possibly the ancestors of the builders of the first Neolithic settlements of the region, which may have been the earliest in the world.

There is some evidence for the deliberate cultivation of cereals, specifically rye, by the Natufian culture, at the Tell Abu Hureyra site, the site for earliest evidence of agriculture in the world. Generally, though, Natufians made use of wild cereals. Animals hunted included gazelles.

In the Levant, there are more than a hundred kinds of cereals, fruits, nuts and other edible parts of plants, and the flora of the Levant during the Natufian period was not the dry, barren, and thorny landscape of today, but parkland and woodland.

The Natufian developed in the same region as the earlier Kebaran complex, and is generally seen as a successor which developed from at least elements within that earlier culture. There were also other cultures in the region, such as the Mushabian culture of the Negev and Sinai, which are sometimes distinguished from the Kebaran, and sometimes also seen as having played a role in the development of the Natufian.

More generally there has been discussion of the similarities of these cultures with those found in coastal North Africa. Graeme Barker notes there are: “similarities in the respective archaeological records of the Natufian culture of the Levant and of contemporary foragers in coastal North Africa across the late Pleistocene and early Holocene boundary”.

Ofer Bar-Yosef has argued that there are signs of influences coming from North Africa to the Levant, citing the microburin technique and “microlithic forms such as arched backed bladelets and La Mouillah points.”

But recent research has shown that the presence of arched backed bladelets, La Mouillah points, and the use of the microburin technique was already apparent in the Nebekian industry of the Eastern Levant, and Maher et al. state that, “Many technological nuances that have often been highlighted as significant during the Natufian were already present during the Early and Middle Epipalaeolithic and do not, in most cases, represent a radical departure in knowledge, tradition, or behavior.”

Authors such as Christopher Ehret have built upon the little evidence available to develop scenarios of intensive usage of plants having built up first in North Africa, as a precursor to the development of true farming in the Fertile Crescent, but such suggestions are considered highly speculative until more North African archaeological evidence can be gathered. In fact, Weiss et al. have shown that the earliest known intensive usage of plants was in the Levant 23,000 years ago at the Ohalo II site.

Anthropologist C. Loring Brace in a recent study on cranial metric traits however, was also able to identify a “clear link” to North African populations for early Natufians based on his observation of gross anatomical similarity with extant populations found mostly in the Sahara. Brace believes that these populations later became assimilated into the broader continuum of Southwest Asian populations.

According to Bar-Yosef and Belfer-Cohen, “It seems that certain preadaptive traits, developed already by the Kebaran and Geometric Kebaran populations within the Mediterranean park forest, played an important role in the emergence of the new socioeconomic system known as the Natufian culture.”

According to one theory, it was a sudden change in climate, the Younger Dryas event (ca. 10800 to 9500 BC), that inspired the development of agriculture. The Younger Dryas was a 1,000-year-long interruption in the higher temperatures prevailing since the Last Glacial Maximum, which produced a sudden drought in the Levant.

This would have endangered the wild cereals, which could no longer compete with dryland scrub, but upon which the population had become dependent to sustain a relatively large sedentary population. By artificially clearing scrub and planting seeds obtained from elsewhere, they began to practice agriculture. However, this theory of the origin of agriculture is controversial in the scientific community.

It is at Natufian sites that some of the earliest archaeological evidence for the domestication of the dog is found. At the Natufian site of Ain Mallaha in Israel, dated to 12 000 BC, the remains of an elderly human and a four-to-five-month-old puppy were found buried together. At another Natufian site at the cave of Hayonim, humans were found buried with two canids.

While the period involved makes it difficult to speculate on any language associated with the Natufian culture, linguists who believe it is possible to speculate this far back in time have written on this subject. As with other Natufian subjects, opinions tend to either emphasize North African connections or Eurasian connections. Hence Alexander Militarev and others have argued that the Natufian may represent the culture which spoke Proto-Afroasiatic which he in turn believes has a Eurasian origin associated with the concept of Nostratic languages.

Some scholars, for example Christopher Ehret, Roger Blench and others, contend that the Afroasiatic Urheimat is to be found in North or North East Africa, probably in the area of Egypt, the Sahara, Horn of Africa or Sudan Within this group, Christopher Ehret, who like Militarev believes Afroasiatic may already have been in existence in the Natufian period, would associate Natufians only with the Near Eastern pre-Proto-Semitic branch of Afroasiatic.

Cayönü

Çayönü is a Neolithic settlement in southern Turkey inhabited around 7200 to 6600 BC. It is located forty kilometres north-west of Diyarbakır, at the foot of the Taurus mountains. It lies near the Bogazcay, a tributary of the upper Tigris River and the Bestakot, an intermittent stream.

Çayönü is possibly the place where the pig (Sus scrofa) was first domesticated. The wild fauna include wild boar, wild sheep, wild goat and cervids. The Neolithic environment included marshes and swamps near the Bogazcay, open wood, patches of steppe and almond-pistachio forest-steppe to the south.

According to Der Spiegel of either 6 March or 3 June 2006, the Max Planck Institute for Plant Breeding Research in Cologne has discovered that the genetically common ancestor of 68 contemporary types of cereal still grows as a wild plant on the slopes of Mount Karaca (Karaca Dağ), which is located in close vicinity to Çayönü. (Compare to information on cereal use in PPNA).

Belbaşı culture

Belbaşı is a cave/rock shelter and a late Paleolithic/Mesolithic site in southern Turkey, located southwest of Antalya. Belbaşı culture tool kit includes tanged arrowheads, triangular points and obliquely truncated blades.

Belbaşı culture is a term sometimes used to describe the prehistoric culture whose clearly identifiable traces in the site were explored in the 1960s, as well as being sometimes used to include also the succeeding Mesolithic/proto-Neolithic culture of Beldibi Cave nearby, at only a few kilometers distance to the north; or, in a wider sense, to cover the entire sequence constituted by half a dozen caves west of Antalya, encompassing, in this sense, also the Neolithic sites at, from south to north, Çarkin, Öküzlü and Karain caves.

Other sources may start the sequence at Beldibi, thus referring to a Beldibi culture, or treat each cave individually. Such a sequence from late Paleolithic to Neolithic in such closely located sites is unknown elsewhere.

Beldibi culture further offers coloured rock engravings on the walls of the cave, hitherto the only known cave art in western Asia, as well as furniture art decorated with naturalistic forms and geometric ornament. Its phases contained imported obsidian, presumably from eastern Taurus Mountains or from the north of the River Gediz, and early forms of pottery. Bones of deer, ibex and cattle occur, and subsistence was likely assisted by coastal fishing from the very close Mediterranean Sea and by the gathering of wild grain. There is as yet no evidence of food production or herding.

Belbaşı culture shows indications of an early connection to the Kebaran industry assemblages of Palestine. Their settlements were stable, typical of Natufian culture sites in this respect, and many later evolved into agricultural villages, similar to Jericho’s forerunner Tell es-Sultan, settled around 7800 BC.

Since the proto-Neolithic of Beldibi being a development from the Mesolithic of Belbaşı is only a possibility, although a strong one, sources differ in their choice of terms for the cultures concerned. The lithic assemblage of both cultures were based upon microliths.

Their most lasting effect was felt not in the Near East, where they seem to have left no permanent mark on the cultural development of Anatolia after 5000 BC, but in Europe, for it was to this new continent that the neolithic cultures of Anatolia introduced the first beginnings of agriculture and stockbreeding.

Old Europe is a term coined by archaeologist Marija Gimbutas to describe what she perceives as a relatively homogeneous and widespread pre-Indo-European Neolithic culture in Europe, particularly in Malta and the Balkans.

In her major work, The Goddesses and Gods of Old Europe: 6500–3500 B.C. (1982), she refers to these Neolithic cultures as Old Europe. Archaeologists and ethnographers working within her framework believe that the evidence points to migrations of the peoples who spoke Indo-European languages at the beginning of the Bronze age (the Kurgan hypothesis). For this reason, Gimbutas and her associates regard the terms Neolithic Europe, Old Europe, and Pre-Indo-European as synonymous.

Baradostian culture

Evidence for human occupation of the Zagros reaches back into the Lower Palaeolithic, as evidenced by the discovery of many cave-sites dating to that period in the Iranian part of the mountain range. Middle Palaeolithic stone tool assemblages are known from Barda Balka, a cave-site south of the Little Zab; and from the Iranian Zagros. A Mousterian stone tool assemblage – produced by either Neanderthals or anatomically modern humans – was recently excavated in Arbil.

Neanderthals also occupied the site of Shanidar. This cave-site, located in the Sapna Valley, has yielded a settlement sequence stretching from the Middle Palaeolithic up to the Epipalaeolithic period. The site is particularly well known for its Neanderthal burials. The Mousterian culture is followed by the Baradostian culture, which is an early Upper Palaeolithic flint industry culture in Zagros region at the border of Iran and Iraq.

Radiocarbon dates suggest that this is one of the earliest Upper Palaeolithic complexes; it may have begun as early as 36000 BC. Its relationship to neighbouring industries however remains unclear. Shanidar Cave in Iraqi Kurdistan, Warwasi rockshelter and Yafteh cave at western Zagros and Eshkaft-e gavi Cave in southern Zagros are among the major sites to be excavated.

Perhaps caused by the maximum cold of the last phase of the most recent ice age or Wurm glaciation the Baradostian was replaced by a local Epi-Palaeolithic industry called the Zarzian culture. This tool tradition marks the end of the Zagros Palaeolithic sequence.

Zarzian culture

Zarzian culture of the Zagros mountains (12,400–8500 BC), stretching northwards into Kobistan in the Caucasus and eastwards into Iran, is an archaeological culture of late Paleolithic and Mesolithic in Iraq, Iran, Central Asia named and recognised of the cave of Zarzi in Iraqi Kurdistan. Here was found plenty of microliths (up to 20% finds). Their forms are short and asymmetric trapezoids, and triangles with hollows.

The Zarzian of the Zagros region of Iran is contemporary with the Natufian, but different from it. The period of the culture is estimated about 18,000-8,000 years BC. It was preceded by the Baradostian culture in the same region and was related to the Imereti culture of the Caucasus.

The only dates for the entire Zarzian come from Palegawra Cave, and date to 17,300-17,000BP, but it is clear that it is broadly contemporary with the Levantine Kebaran, with which it shares features. It seems to have evolved from the Upper Palaeolithic Baradostian.

There are only a few Zarzian sites and the area appears to have been quite sparsely populated during the Epipalaeolithic. Faunal remains from the Zarzian indicate that the temporary form of structures indicate a hunter-gatherer subsistence strategy, focused on onager, red deer and caprines. Better known sites include Palegawra Cave, Shanidar B2 and Zarzi.

The Zarzian culture is found associated with remains of the domesticated dog and with the introduction of the bow and arrow. It seems to have extended north into the Kobistan region and into Eastern Iran as a forerunner of the Hissar and related cultures.

The Zarzian culture seems to have participated in the early stages of what Kent Flannery has called the broad spectrum revolution (BSR). He suggested that the emergence of the Neolithic in southwest Asia was prefaced by increases in dietary breadth among foraging societies.

The broad spectrum revolution

It has been proposed that the broad spectrum revolution (BSR) of Kent Flannery (1969), associated with microliths, the use of the bow and arrow, and the domestication of the dog, all of which are associated with these cultures, may have been the cultural “motor” that led to their expansion.

Certainly cultures which appeared at Franchthi Cave in the Aegean and Lepenski Vir in the Balkans, and the Murzak-Koba (9100–8000 BCE) and Grebenki (8500–7000 BCE) cultures of the Ukrainian steppe, all displayed these adaptations.

The broad spectrum revolution followed the ice age around 15,000 BP in the Middle East and 12,000 BP in Europe. During this time, there was a transition from focusing on a few main food sources to gathering/hunting a “broad spectrum” of plants and animals.

Flannery’s hypothesis was meant to help explain the adoption of agriculture. Unpersuaded by “the facile explanation of prehistoric environmental change,” he suggested (following Lewis Binford’s equilibrium model) that population growth in optimal habitats led to demographic pressure within nearby marginal habitats as daughter groups migrated.

The search for more food within these marginal habitats forced foragers to diversify the types of food sources harvested, broadening the subsistence base outward to include more fish, small game, water fowl, invertebrates likes snails and shellfish, as well as previously ignored or marginal plant sources.

Most importantly, Flannery argues that the need for more food in these marginal environments led to the delibrate cultivation of certain plants species, especially cereals. In optimal habitats, these plants naturally grew in relatively dense stands, but required human intervention in order to be efficiently harvested in marginal zones. Thus, the broad spectrum revolution set the stage for domestication and rise of permanent agricultural settlement.

A broad spectrum revolution is likely to manifest as both an increased spectrum of food resources and an evenness in the exploitation of high- and low-value prey. Under a broad spectrum economy a greater amount of low-value prey (i.e. high cost-to-benefit ratio) would be included because there are insufficient high-value prey to reliably satisfy a population’s needs.

In terms of plants, it would be expected that foodstuff previously ignored because of the difficult in their extraction are now included in a diet. Whereas, animal prey which was previously considered an inefficient use of resources (particularly small, fast mammals or fish) may also be included.

In the Middle East, the broad spectrum revolution led to an increase in the production of food. The growth and reproduction of certain plants and animals became vastly popular. Because large animals became quite scarce, people had to find new resources of food and tools elsewhere. Interests focused on smaller game like fish, rabbits, and shellfish because the reproduction rate on small animals is much greater than that of large animals.

The most commonly accepted stimulation for the BSR is demographic pressures on the landscape, under which over-exploitation of resources meant narrows diets restricted to high-value prey could no longer feed the expanding population.

The Broad Spectrum Revolution has also been linked to climatic changes, including sea level rises during which conditions became more inviting to marine life offshore in shallow, warm waters. Quantity and variety of marine life increased drastically as did the number of edible species.

Because the rivers’ power weakened with rising waters, the currents flowing into the ocean were slow enough to allow salmon and other fish ascend upstream to spawn. Birds found refuge next to riverbeds in marsh grasses and then proceeded to migrate across Europe in the wintertime.

Domestication

The Middle East served as the source for many animals that could be domesticated, such as sheep, goats and pigs. This area was also the first region to domesticate the dromedary camel. Henri Fleisch discovered and termed the Shepherd Neolithic flint industry from the Bekaa Valley in Lebanon and suggested that it could have been used by the earliest nomadic shepherds. He dated this industry to the Epipaleolithic or Pre-Pottery Neolithic (PPN) as it is evidently not Paleolithic, Mesolithic or even Pottery Neolithic.

The presence of these animals gave the region a large advantage in cultural and economic development. As the climate in the Middle East changed, and became drier, many of the farmers were forced to leave, taking their domesticated animals with them. It was this massive emigration from the Middle East that would later help distribute these animals to the rest of Afroeurasia.

This emigration was mainly on an east-west axis of similar climates, as crops usually have a narrow optimal climatic range outside of which they cannot grow for reasons of light or rain changes. For instance, wheat does not normally grow in tropical climates, just like tropical crops such as bananas do not grow in colder climates.

This East-West axis is the main reason why plant and animal domestication spread so quickly from the Fertile Crescent to the rest of Eurasia and North Africa, while it did not reach through the North-South axis of Africa to reach the Mediterranean climates of South Africa, where temperate crops were successfully imported by ships in the last 500 years.

The African Zebu is a separate breed of cattle that was better suited to the hotter climates of central Africa than the fertile-crescent domesticated bovines. North and South America were similarly separated by the narrow tropical Isthmus of Panama, that prevented the llama to be exported from the Andes to the Mexican plateau.

Hamoukar

Hamoukar is a large archaeological site located in the Jazira region of northeastern Syria near the Iraqi border (Al Hasakah Governorate) and Turkey. The discovery at Hamoukar indicates that some of the fundamental ideas behind cities – including specialization of labor, a system of laws and government, and artistic development – may have begun earlier than was previously believed.

The fact that this discovery is such a large city is what is most exciting to archaeologists. While they have found small villages and individual pieces that date much farther back than Hamoukar, nothing can quite compare to the discovery of this size and magnitude.

This archaeological discovery suggests that civilizations advanced enough to reach the size and organizational structure that was necessary to be considered a city could have actually emerged before the advent of a written language. Previously it was believed that a system of written language was a necessary predecessor of that type of complex city.

The Excavations have shown that this site houses the remains of one of the world’s oldest known cities, leading scholars to believe that cities in this part of the world emerged much earlier than previously thought.

Traditionally, the origins of urban developments in this part of the world have been sought in the riverine societies of southern Mesopotamia (in what is now southern Iraq).

This is the area of ancient Sumer, where around 4000 BC many of the famous Mesopotamian cities such as Ur and Uruk emerged, giving this region the attributes of “Cradle of Civilization” and “Heartland of Cities.” Following the discoveries at Hamoukar, this definition may have to extended further up the Tigris River to include that part of northern Syria where Hamoukar is located.

Most importantly, archaeologists believe this apparent city was thriving as far back as 4000 BC and independently from Sumer. Until now, the oldest cities with developed seals and writing were thought to be Sumerian Uruk and Ubaid in Mesopotamia, which would be in the southern one-third of Iraq today.

Excavation work undertaken in 2005 and 2006 has shown that this city was destroyed by warfare by around 3500 BC – probably the earliest urban warfare attested so far in the archaeological record of the Near East.

The Pre-Pottery Neolithic (PPN)

The Pre-Pottery Neolithic (PPN) (around 8,500-5,500 BCE) represents the early Neolithic in the Levantine and upper Mesopotamian region of the Fertile Crescent. It succeeds the Natufian culture of the Epipaleolithic (Mesolithic) as the domestication of plants and animals was in its beginnings and triggered by the Younger Dryas.

The Pre-Pottery Neolithic is divided into Pre-Pottery Neolithic A (PPNA 8,500 BCE – 7,600 BCE) and the following Pre-Pottery Neolithic B (PPNB 7,600 BCE – 6,000 BCE). These were originally defined by Kathleen Kenyon in the type site of Jericho (Palestine).

The Pre-Pottery Neolithic culture came to an end around the time of the 8.2 kiloyear event, a cool spell lasting several hundred years centred around 6200 BCE. The Pre-Pottery Neolithic precedes the ceramic Neolithic (Yarmukian). At ‘Ain Ghazal in Jordan the culture continued a few more centuries as the so-called Pre-Pottery Neolithic C culture.

Pre-Pottery Neolithic A

Main article: Pre-Pottery Neolithic A

Around 8,000 BCE during the Pre-Pottery Neolithic A (PPNA) the world’s first town Jericho appeared in the Levant.

Pre-Pottery Neolithic A (PPNA)

Pre-Pottery Neolithic A (PPNA) denotes the first stage in early Levantine Neolithic culture, dating around 8000 to 7000 BCE. Archaeological remains are located in the Levantine and upper Mesopotamian region of the Fertile Crescent. The time period is characterized by tiny circular mud brick dwellings, the cultivation of crops, the hunting of wild game, and unique burial customs in which bodies were buried below the floors of dwellings.

The Pre-Pottery Neolithic A and the following Pre-Pottery Neolithic B were originally defined by Kathleen Kenyon in the type site of Jericho (Palestine). During this time, pottery was yet unknown. They precede the ceramic Neolithic (Yarmukian). PPNA succeeds the Natufian culture of the Epipaleolithic (Mesolithic).

Settlements

PPNA archaeological sites are much larger than those of the preceding Natufian hunter-gatherer culture, and contain traces of communal structures, such as the famous tower of Jericho. PPNA settlements are characterized by round, semi-subterranean houses with stone foundations and terrazzo-floors. The upper walls were constructed of unbaked clay mudbricks with plano-convex cross-sections. The hearths were small, and covered with cobbles. Heated rocks were used in cooking, which led to an accumulation of fire-cracked rock in the buildings, and almost every settlement contained storage bins made of either stones or mud-brick.

One of the most notable PPNA settlements is Jericho, thought to be the world’s first town (c 8000 BC). The PPNA town contained a population of up to 2000-3000 people, and was protected by a massive stone wall and tower. There is much debate over the function of the wall, for there is no evidence of any serious warfare at this time. One possibility is the wall was built to protect the salt resources of Jericho.

Burial Practices

PPNA cultures are unique for their burial practices, and Kenyon (who excavated the PPNA level of Jericho), characterized them as “living with their dead.” Kenyon found no fewer than 279 burials, below floors, under household foundations, and in between walls. In the PPNB period, skulls were often dug up and reburied, or mottled with clay and (presumably) displayed.

Lithics

The lithic industry is based on blades struck from regular cores. Sickle-blades and arrowheads continue traditions from the late Natufian culture, transverse-blow axes and polished adzes appear for the first time.

Crop Cultivation and Granaries

Sedentism of this time allowed for the cultivation of local grains, such as barley and wild oats, and for storage in granaries. Sites such as Dhra′ and Jericho retained a hunting lifestyle until the Pre-Pottery Neolithic B period, but granaries allowed for year-round occupation. This period of cultivation is considered “pre-domestication”, but may have begun to develop plant species into the domesticated forms they are today. Deliberate, extended-period storage was made possible by the use of “suspended floors for air circulation and protection from rodents”. This practice “precedes the emergence of domestication and large-scale sedentary communities by at least 1,000 years”.

Granaries are positioned in places between other buildings early on 9500 BC. However beginning around 8500 BC, they were moved inside houses, and by 7500 BC storage occurred in special rooms. This change might reflect changing systems of ownership and property as granaries shifted from a communal use and ownership to become under the control of households or individuals. It has been observed of these granaries that their “sophisticated storage systems with subfloor ventilation are a precocious development that precedes the emergence of almost all of the other elements of the Near Eastern Neolithic package—domestication, large scale sedentary communities, and the entrenchment of some degree of social differentiation.” Moreover, “Building granaries may … have been the most important feature in increasing sedentism that required active community participation in new life-ways.”

Regional variants

With more sites becoming known, archaeologists have defined a number of regional variants:

‘Sultanian’ in the Jordan River valley and southern Levant with the type site of Jericho. Other sites include Netiv HaGdud, El-Khiam, Hatoula and Nahal Oren.

‘Mureybetian’ in the Northern Levant. Defined by the finds from Mureybet IIIA, IIIB, typical: Helwan points, sickle-blades with base amenagée or short stem and terminal retouch. Other sites include Sheyk Hasan and Jerf el-Ahmar.

Mureybet is a tell, or ancient settlement mound, located on the west bank of the Euphrates in Ar-Raqqah Governorate, northern Syria. The site was excavated between 1964 and 1974 and has since disappeared under the rising waters of Lake Assad.

Mureybet was occupied between 10,200 and 8,000 BC and is the eponymous type site for the Mureybetian culture, a subdivision of the Pre-Pottery Neolithic A (PPNA). In its early stages, Mureybet was a small village occupied by hunter-gatherers. Hunting was important and crops were first gathered and later cultivated, but they remained wild. During its final stages, domesticated animals were also present at the site.

‘Aswadian’ in the Damascus Basin. Defined by finds from Tell Aswad IA. Typical: bipolar cores, big sickle blades, Aswad points. The ‘Aswadian’ variant was recently abolished by the work of Danielle Stordeur in her initial report from further investigations in 2001–2006. The PPNB horizon was moved back at this site, to around 8700 BC.

Tell Aswad (“Black hill”), Su-uk-su or Shuksa, is a large prehistoric, Neolithic Tell, about 5 hectares (540,000 sq ft) in size, located around 48 kilometres (30 mi) from Damascus in Syria, on a tributary of the Barada River at the eastern end of the village of Jdeidet el Khass.

Tools and weapons were made of flint including Aswadian and Jericho point arrowheads. Other finds included grinding equipment, stone and mud containers, and ornaments made of various materials. Obsidian was imported from Anatolia. Tell Aswad occupies a special location in the central Levant as a connecting region between northern and southern expansions of agriculture.

Sites in ‘Upper Mesopotamia’ include Çayönü and Göbekli Tepe.

Pre-Pottery Neolithic B

Main article: Pre-Pottery Neolithic B

Pre-Pottery Neolithic B (PPNB) differed from PPNA in showing greater use of domesticated animals, a different set of tools, and new architectural styles.

Pre-Pottery Neolithic B (PPNB)

Pre-Pottery Neolithic B (PPNB) is a division of the Neolithic developed by Dame Kathleen Kenyon during her archaeological excavations at Jericho in the southern Levant region. The period is dated to between ca. 10700 and ca. 8000 BP or 7000 – 6000 BCE.

Like the earlier PPNA people, the PPNB culture developed from the Earlier Natufian but shows evidence of a northerly origin, possibly indicating an influx from the region of north eastern Anatolia.

Cultural tendencies of this period differ from that of the earlier Pre-Pottery Neolithic A period in that people living during this period began to depend more heavily upon domesticated animals to supplement their earlier mixed agrarian and hunter-gatherer diet. In addition the flint tool kit of the period is new and quite disparate from that of the earlier period. One of its major elements is the naviform core.

This is the first period in which architectural styles of the southern Levant became primarily rectilinear; earlier typical dwellings were circular, elliptical and occasionally even octagonal. Pyrotechnology was highly developed in this period. During this period, one of the main features of houses is evidenced by a thick layer of white clay plaster floors highly polished and made of lime produced from limestone.

It is believed that the use of clay plaster for floor and wall coverings during PPNB led to the discovery of pottery. Indeed, the earliest proto-pottery was White Ware Vessels, made from lime and gray ash, built up around baskets before firing, for several centuries around 7000 BC at sites such as Tell Neba’a Faour (Beqaa Valley). Sites from this period found in the Levant utilizing rectangular floor plans and plastered floor techniques were found at Ain Ghazal, Yiftahel (western Galilee), and Abu Hureyra (Upper Euphrates).

Megiddo (Hebrew: Tell al-Mutesellim; 7000-586 BC – the same time as the destruction of the First Israelite Temple in Jerusalem by the Babylonians, and subsequent fall of Israelite rule and exile) is a tell in modern Israel near Kibbutz Megiddo, about 30km south-east of Haifa, known for its historical, geographical, and theological importance, especially under its Greek name Armageddon.

Megiddo was a site of great importance in the ancient world. In ancient times Megiddo was an important city-state. Megiddo is strategically located at the head of a pass through the Carmel Ridge overlooking the Jezreel Valley from the west. It guarded the western branch of a narrow pass and trade route connecting Egypt and Assyria. Because of its strategic location, Megiddo was the site of several historical battles. Excavations have unearthed 26 layers of ruins, indicating a long period of settlement.

Since this time it has remained uninhabited, preserving ruins pre-dating 586 BC without settlements ever disturbing them. Instead, the town of Lajjun (not to be confused with the el-Lajjun archaeological site in Jordan) was built up near to the site, but without inhabiting or disturbing its remains.

Danielle Stordeur’s recent work at Tell Aswad, a large agricultural village between Mount Hermon and Damascus could not validate Henri de Contenson’s earlier suggestion of a PPNA Aswadian culture. Instead, they found evidence of a fully established PPNB culture at 8700 BC at Aswad, pushing back the period’s generally accepted start date by 1200 years.

How a PPNB culture could spring up in this location, practicing domesticated farming from 8700 BC has been the subject of speculation. Whether it created its own culture or imported traditions from the North East or Southern Levant has been considered an important question for a site that poses a problem for the scientific community.

The culture disappeared during the 8.2 kiloyear event, a term that climatologists have adopted for a sudden decrease in global temperatures that occurred approximately 8200 years before the present, or c. 6200 BCE, and which lasted for the next two to four centuries.

Pre-Pottery Neolithic C

Main article: Pre-Pottery Neolithic C

Work at the site of ‘Ain Ghazal in Jordan has indicated a later Pre-Pottery Neolithic C (PPNC) period which lasted between 8200 and 7900 BP.

Juris Zarins has proposed that a Circum Arabian Nomadic Pastoral Complex developed in the period from the climatic crisis of 6,200 BCE. Cultures practicing this lifestyle spread down the Red Sea shoreline and moved east from Syria into Southern Iraq.

This partly as a result of an increasing emphasis in PPNB cultures upon animal domesticates, and a fusion with Harifian hunter gatherers in the Southern Levant, with affiliate connections with the cultures of Fayyum and the Eastern Desert of Egypt.

Pre-Pottery Neolithic C (PPNC)

In the following Munhatta and Yarmukian post-pottery Neolithic cultures that succeeded it, rapid cultural development continues, although PPNB culture continued in the Amuq valley, where it influenced the later development of Ghassulian culture.

Work at the site of ‘Ain Ghazal in Jordan has indicated a later Pre-Pottery Neolithic C (PPNC) period which lasted between 8200 and 7900 BP. ‘Ain Ghazal is a Neolithic site located in North-Western Jordan, on the outskirts of Amman. It dates as far back as 7250 BC, and was inhabited until 5000 BC. At 15 hectares (37 ac), ‘Ain Ghazal ranks as one of the largest known prehistoric settlements in the Near East.

Juris Zarins has proposed that a Circum Arabian Nomadic Pastoral Complex developed in the period from the climatic crisis of 6,200 BCE. Cultures practicing this lifestyle spread down the Red Sea shoreline and moved east from Syria into Southern Iraq.

This partly as a result of an increasing emphasis in PPNB cultures upon animal domesticates, and a fusion with Harifian hunter gatherers in the Southern Levant, with affiliate connections with the cultures of Fayyum and the Eastern Desert of Egypt.

The Yarmukian culture (6400–6000 BC) is a Neolithic culture of the ancient Levant. It was the first culture in Prehistoric Israel and one of the oldest in the Levant to make use of pottery. The Yarmukian derives its name from the Yarmouk River which flows near its type site at Sha’ar HaGolan, a kibbutz at the foot of the Golan Heights.

The first Yarmukian settlement was unearthed at Megiddo during the 1930s, but was not identified as a distinct Neolithic culture at the time. At Sha’ar HaGolan, in 1949, Prof. Moshe Stekelis first identified the Yarmukian Culture, a Pottery Neolithic culture that inhabited parts of Israel and Jordan.

The site, dated to ca. 6400–6000 BC (calibrated), is located in the central Jordan Valley, on the northern bank of the Yarmouk River. Its size is circa 20 hectares, making it one of the largest settlements in the world at that time. Although other Yarmukian sites have been identified since, Sha’ar HaGolan is the largest, probably indicating its role as the Yarmukian center.

The greatest technological innovation of the Sha’ar HaGolan Neolithic was the manufacture of pottery. This industry, which appears here for the first time in Israel, gives this cultural stage its name of Pottery Neolithic. The pottery vessels are in a variety of shapes and sizes and were put to various domestic uses.

Besides the site at Sha’ar HaGolan, 20 other Yarmukian sites have been identified in Israel, Jordan and Lebanon. These include:

- Tel Megiddo (Israel)

- Ain Ghazal (Jordan)

- Munhata (Israel)

- Tel Qishion (Israel)

- Hamadiya (Israel)

- Ain Rahub (Jordan)

- Abu Tawwab (Jordan)

Although the Yarmukian culture occupied limited regions of northern Israel and northern Jordan, Yarmukian pottery has been found elsewhere in the region, including the Habashan Street excavations in Tel-Aviv and as far north as Byblos, Lebanon.

Ghassulian refers to a culture and an archaeological stage dating to the Middle Chalcolithic Period in the Southern Levant (c. 3800–c. 3350 BC). Considered to correspond to the Halafian culture of North Syria and Mesopotamia, its type-site, Tulaylat al-Ghassul, is located in the Jordan Valley near the Dead Sea in modern Jordan and was excavated in the 1930s.

The Ghassulian stage was characterized by small hamlet settlements of mixed farming peoples, and migrated southwards from Syria into Israel. Houses were trapezoid-shaped and built mud-brick, covered with remarkable polychrome wall paintings. Their pottery was highly elaborate, including footed bowls and horn-shaped drinking goblets, indicating the cultivation of wine. Several samples display the use of sculptural decoration or of a reserved slip (a clay and water coating partially wiped away while still wet). The Ghassulians were a Chalcolithic culture as they also smelted copper.

Funerary customs show evidence that they buried their dead in stone dolmens.

Ghassulian culture has been identified at numerous other places in what is today southern Israel, especially in the region of Beersheba. The Ghassulian culture correlates closely with the Amratian of Egypt and may have had trading affinities (e.g., the distinctive churns, or “bird vases”) with early Minoan culture in Crete.

Ghassulian culture replaced the Minhata and Yarmukian culture, and seems to have developed in part from a fusion of Pre-Pottery Neolithic B in the Amuq Valley, with Minhata and nomadic pastoralists of the circum Arabian nomadic pastoral complex. It was associated with the Older Peron, which began in the 5000 BCE to 4900 BCE era, and lasted to about 4100 BCE, a period of generally clement and balmy weather conditions that favored plant growth.

The Ghassulian phase seems to have been formative for the Canaanite civilization – in which a chalcolithic structure pioneered a Mediterranean mixed economy, involving the intensive subsistence production of horticultural fruit and vegetables, extensive farming of grains and cereals, transhumance and nomadic pastoral systems of animal husbandry, and commercial production (as in Crete) of wine and olives.

The Origins of Farming in South-West Asia

Pre-history of the Southern Levant

History of pottery in the Southern Levant

Chalcolithic Temple of Ein Gedi

The Human Journey: The Neolithic Era

Archaeologist finds traces of ‘humanity’s first war’ in Syria

Geographical Effects on Armenian self-identity

The Origins & Spread of Near Eastearn Agriculture

Chronological Chart:

Download radiocarbon CONTEXT database chronology chart 2006 (PDF) 33 KB

Jordbrukets historie:

Download map P5c – Halaf 5.600 – 5.200 calBC (png) 267 KB

Download map P5b – Early Halaf 6.000 – 5.600 calBC (png) 268 KB

Download map P5a – Yarmukian/Amuq B/Pre-Halaf 6.300 – 6.000 calBC (png) 269 KB

Download map P4c – PPNC/early PN/Amuq A 6.600 – 6.300 calBC (png) 262 KB

Download map P4b – PPNC/earliest PN 7.100 – 6.600 calBC (png) 253 KB

Download map P4a – LPPNB 7.600 – 7.100 calBC (png) 259 KB

Download map P3b – MPPNB 8.200 – 7.600 calBC (png) 256 KB

Download map P3a – EPPNB 8.800 – 8.200 calBC (png) 261 KB

Download map P2b – PPNA 9.500 – 8.800 calBC (png) 261 KB

Download map P2a – late Natufian?/PPNA? Natufian 10.000 – 9.500 calBC (png) 254 KB

Download map P1b – late Natufian 11.000 – 10.000 calBC (png) 238 KB

Download map P1a – early Natufian 12.500 – 11.000 calBC (png) 247 KB

Download map P0b – Geom. Kebaran 16.000 – 12.500 calBC (png) 243 KB

Download map P0a – Kebaran 21.500 – 16.000 calBC (png) 253 KB

Central Asia and a representation of the major courses of the ‘Silk Roads’, indicating the pivotal western region.

Sling bullets

Sling bullets

Leave a comment