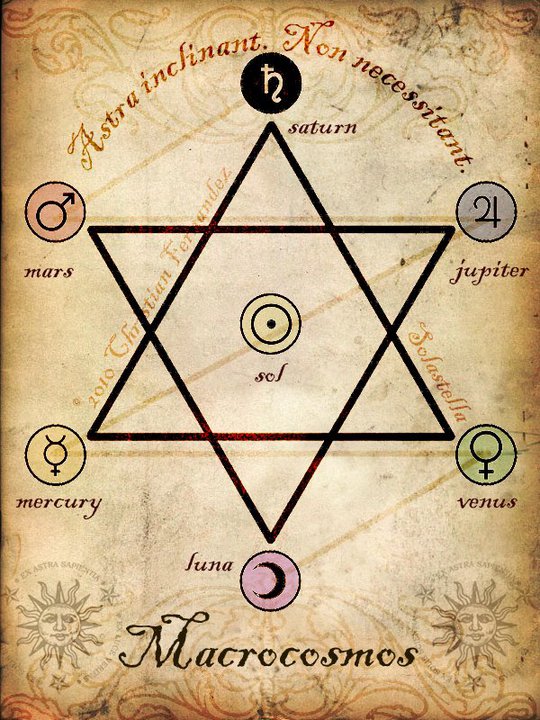

AN (Dumuzid / Nergal) – Uranus (Dionysus / Mars-Apollo-Pluto) – Balder / Tyr (60)

Enlil – Saturn – Njord (50)

Enki – Neptune – Heimdall (40)

In Mesopotamian religion, Anu was the personification of the sky, the utmost power, the supreme God, the one “who contains the entire universe”. He was identified with the north ecliptic pole centered in Draco.

His name meant the “One on High”, and together with his sons Enlil and Enki (Ellil and Ea in Akkadian), he formed a triune conception of the divine, in which Anu represented a “transcendental” obscurity, Enlil the “transcendent” and Enki the “immanent” aspect of the divine.

In astral theology, the three—Anu, Enlil and Enki—also personified the three bands of the sky, and the contained constellations, spinning around the ecliptic, respectively the middle, northern and southern sky.

The Amorite god Amurru or Martu was sometimes equated with Anu. Hadad, Adad (Akkadian) or Iškur (Sumerian) was the storm and rain god in the Northwest Semitic and ancient Mesopotamian religions. Later, during the Seleucid Empire (213 BC — 63 BC), Anu was identified with Enmešara (Nergal) and Dumuzid (Tammuz).

Ninshubar-Papsukkal – Mercury – Odin

An

Anu (Akkadian: 𒀭𒀭 DAN, Anu‹m›; Sumerian: 𒀭 AN, from 𒀭 an “sky, heaven”) is the earliest attested sky-father deity. In Sumerian religion, he was also “King of the Gods”, “Lord of the Constellations, Spirits and Demons”, and “Supreme Ruler of the Kingdom of Heaven”, where Anu himself wandered the highest Heavenly Regions.

He was believed to have the power to judge those who had committed crimes, and to have created the stars as soldiers to destroy the wicked. His attribute was the Royal Tiara. His attendant and vizier was the god Ilabrat.

In Sumerian texts of the third millennium the goddess Uraš is his consort; later this position was taken by Ki, the personification of earth, and in Akkadian texts by Antu, whose name is probably derived from his own.

Dingir (𒀭, usually transliterated DIĜIR) is a Sumerian word for “god.” The sign originated as a star-shaped ideogram indicating a god in general, or the Sumerian god An, the supreme father of the gods.

Its cuneiform sign is most commonly employed as the determinative for religious names and related concepts, in which case it is not pronounced and is conventionally transliterated as a superscript “D” as in e.g. DInanna.

The cuneiform sign by itself was originally an ideogram for the Sumerian word an (“sky” or “heaven”); its use was then extended to a logogram for the word diĝir (“god” or goddess) and the supreme deity of the Sumerian pantheon An, and a phonogram for the syllable /an/.

Akkadian took over all these uses and added to them a logographic reading for the native ilum and from that a syllabic reading of /il/. In Hittite orthography, the syllabic value of the sign was again only an.

The concept of “divinity” in Sumerian is closely associated with the heavens, as is evident from the fact that the cuneiform sign doubles as the ideogram for “sky”, and that its original shape is the picture of a star.

Dingir also meant sky or heaven in contrast with ki which meant earth. The original association of “divinity” is thus with “bright” or “shining” hierophanies in the sky.

The doctrine once established remained an inherent part of the Babylonian-Assyrian religion and led to the more or less complete disassociation of the three gods constituting the triad from their original local limitations. An intermediate step between Anu viewed as the local deity of Uruk, Enlil as the god of Nippur, and Ea as the god of Eridu.

Anu existed in Sumerian cosmogony as a dome that covered the flat earth. However, in the astral theology of Babylonia and Assyria, Anu, Enlil, and Ea became the three zones of the ecliptic, the northern, middle and southern zone respectively.

When Enlil rose to equal or surpass An in authority, the functions of the two deities came to some extent to overlap. An was also sometimes equated with Amurru, and, in Seleucid Uruk, with Enmešara (Nergal) and Dumuzi.

Nergal

Nergal was a deity worshipped throughout Mesopotamia. Nergal seems to be in part a solar deity, sometimes identified with Shamash, but only representative of a certain phase of the sun. Portrayed in hymns and myths as a god of war and pestilence, Nergal seems to represent the sun of noontime and of the summer solstice that brings destruction, high summer being the dead season in the Mesopotamian annual cycle. He has also been called “the king of sunset”.

Over time Nergal developed from a war god to a god of the underworld. In the mythology, this occurred when Enlil and Ninlil gave him the underworld. In this capacity he has associated with him a goddess Allatu or Ereshkigal, though at one time Allatu may have functioned as the sole mistress of Aralu, ruling in her own person. In some texts the god Ninazu is the son of Nergal and Allatu/Ereshkigal.

In the late Babylonian astral-theological system Nergal is related to the planet Mars. As a fiery god of destruction and war, Nergal doubtless seemed an appropriate choice for the red planet, and he was equated by the Greeks to the war-god Ares (Latin Mars)—hence the current name of the planet.

Amongst the Hurrians and later Hittites Nergal was known as Aplu, a name derived from the Akkadian Apal Enlil, (Apal being the construct state of Aplu) meaning “the son of Enlil”. Aplu may be related with Apaliunas who is considered to be the Hittite reflex of *Apeljōn, an early form of the name Apollo.

Apaliunas is attested in a Hittite language treaty as a protective deity of Wilusa, a major city of the late Bronze Age in western Anatolia described in 13th century BC Hittite sources as being part of a confederation named Assuwa. The city is often identified with the Troy of the Ancient Greek Epic Cycle.

In Babylonian astronomy, the stars Castor and Pollux were known as the Great Twins (MUL.MASH.TAB.BA.GAL.GAL). The Twins were regarded as minor gods and were called Meshlamtaea and Lugalirra, meaning respectively ‘The One who has arisen from the Underworld’ and the ‘Mighty King’. Both names can be understood as titles of Nergal, the major Babylonian god of plague and pestilence, who was king of the Underworld.

Uranus / Caelus-Summanus

Uranus (meaning “sky” or “heaven”) was the primal Greek god personifying the sky. He was the brother of Pontus (“Sea”), an ancient, pre-Olympian sea-god, one of the Greek primordial deities.

Uranus (meaning “sky” or “heaven”) was the primal Greek god personifying the sky. He was the brother of Pontus (“Sea”), an ancient, pre-Olympian sea-god, one of the Greek primordial deities.

In Ancient Greek literature, Uranus or Father Sky was the son and husband of Gaia, Mother Earth. According to Hesiod’s Theogony, Uranus was conceived by Gaia alone, but other sources cite Aether as his father.

Uranus and Gaia were the parents of the first generation of Titans, and the ancestors of most of the Greek gods, but no cult addressed directly to Uranus survived into Classical times, and Uranus does not appear among the usual themes of Greek painted pottery.

His name in Roman mythology was Caelus, a primal god of the sky in Roman myth and theology, iconography, and literature (compare caelum, the Latin word for “sky” or “the heavens”, hence English “celestial”).

Caelus is coupled with Terra (Earth) as pater and mater (father and mother). He has been associated with Summanus, the god of nocturnal thunder, as counterposed to Jupiter, the god of diurnal (daylight) thunder.

According to Cicero and Hyginus, Caelus was the son of Aether and Dies (“Day” or “Daylight”). Caelus and Dies were in this tradition the parents of Mercury. With Trivia, Caelus was the father of the distinctively Roman god Janus, as well as of Saturn and Ops. Caelus was also the father of one of the three forms of Jupiter, the other two fathers being Aether and Saturn.

The name Summanus is thought to be from Summus Manium “the greatest of the Manes”, or sub-, “under” + manus, “hand”. According to Martianus Capella, Summanus is another name for Pluto as the “highest” (summus) of the Manes.

Every June 20, the day before the summer solstice, round cakes called summanalia, made of flour, milk and honey and shaped as wheels, were offered to him as a token of propitiation: the wheel might be a solar symbol.

Saint Augustine records that in earlier times Summanus had been more exalted than Jupiter, but with the construction of a temple that was more magnificent than that of Summanus, Jupiter became more honored.

Uranus, the planet

The planet Uranus is very unusual among the planets in that it rotates on its side, so that it presents each of its poles to the Sun in turn during its orbit; causing both hemispheres to alternate between being bathed in light and lying in total darkness over the course of the orbit.

Astrological interpretations associate Uranus with the principles of ingenuity, new or unconventional ideas, individuality, discoveries, electricity, inventions, democracy, and revolutions. Uranus, among all planets, most governs genius.

Uranus governs societies, clubs, and any group based on humanitarian or progressive ideals. Uranus, the planet of sudden and unexpected changes, rules freedom and originality. In society, it rules radical ideas and people, as well as revolutionary events that upset established structures. Uranus is also associated with Wednesday, alongside Mercury (since Uranus is in the higher octave of Mercury).

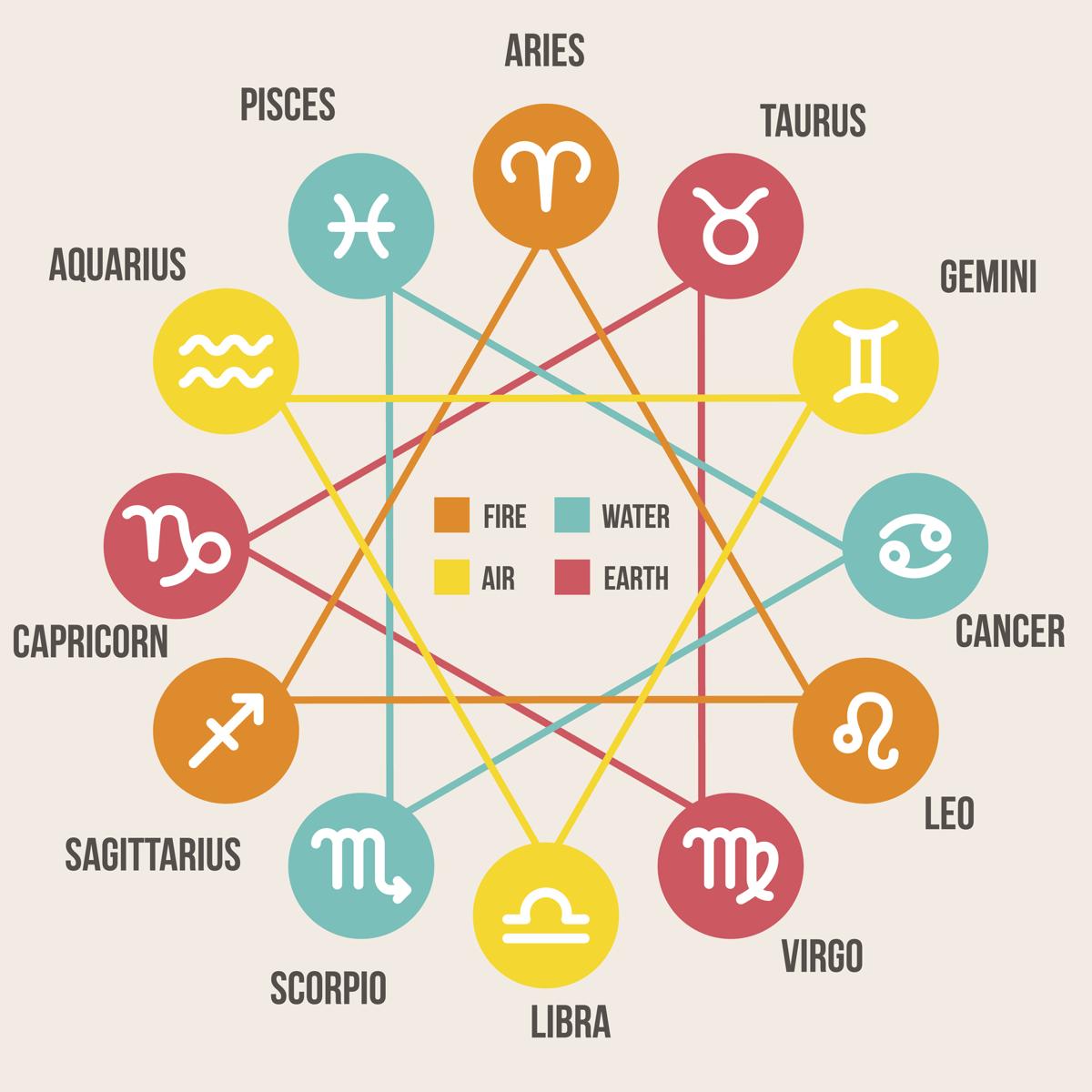

Aquarius and Scorpio

Uranus is the ruling planet of Aquarius and is exalted in Scorpio. Aquarius is a constellation of the zodiac. It is the eleventh astrological sign in the Zodiac, originating from the constellation Aquarius.

Under the tropical zodiac, the sun is in Aquarius typically between January 21 and February 18, while under the Sidereal Zodiac, the sun is in Aquarius from approximately February 15 to March 14, depending on leap year.

Its name is Latin for “water-carrier” or “cup-carrier”, and its symbol is a representation of water. Aquarius is identified as GU.LA “The Great One” in the Babylonian star catalogues and represents the god Enki himself, who is commonly depicted holding an overflowing vase.

Aquarius is also associated with the Age of Aquarius, a concept popular in 1960s counterculture. Despite this prominence, the Age of Aquarius will not dawn until the year 2597, as an astrological age does not begin until the Sun is in a particular constellation on the vernal equinox.

Scorpio is the eighth astrological sign in the Zodiac, originating from the constellation of Scorpius. It spans 210°–240° ecliptic longitude. Under the tropical zodiac (most commonly used in Western astrology), the sun transits this area on average from October 23 to November 21. Under the sidereal zodiac (most commonly used in Hindu astrology), the sun is in Scorpio from approximately November 16 to December 15.

In ancient times, Scorpio was associated with the planet Mars. After Pluto was discovered in 1930, it became associated with Scorpio instead. Scorpio is also associated with the Greek deity, Artemis, who is said to have created the constellation Scorpius.

The Babylonians called this constellation MUL.GIR.TAB – the ‘Scorpion’, the signs can be literally read as ‘the (creature with) a burning sting’. In some old descriptions the constellation of Libra is treated as the Scorpion’s claws. Libra was known as the Claws of the Scorpion in Babylonian (zibānītu (compare Arabic zubānā)).

Mars

Mars & Venus

In ancient Roman religion and myth, Mars was the god of war and also an agricultural guardian, a combination characteristic of early Rome. The month Martius was the beginning of the season for warfare, and the festivals held in his honor during the month were mirrored by others in October, when the season for these activities came to a close.

The name of March comes from Martius, the first month of the earliest Roman calendar. It was named after Mars. In many languages, Tuesday is named for the planet Mars or the god of war: In Latin, martis dies (“Mars’s Day”), survived in Romance languages as martes (Spanish), mardi (French), martedi (Italian), marţi (Romanian), and dimarts (Catalan). In Irish (Gaelic), the day is An Mháirt, while in Albanian it is e Marta.

The English word Tuesday derives from Old English “Tiwesdæg” and means “Tiw’s Day”, Tiw being the Old English form of the Proto-Germanic war god *Tîwaz, or Týr in Norse.

The word Mārs (genitive Mārtis), which in Old Latin and poetic usage also appears as Māvors (Māvortis), is cognate with Oscan Māmers (Māmertos). The Old Latin form was believed to derive from an Italic *Māworts, but can also be explained as deriving from Maris, the name of an Etruscan child-god; scholars have varying views on whether the two gods are related, and if so how.

The spear is the instrument of Mars in the same way that Jupiter wields the lightning bolt, Neptune the trident, and Saturn the scythe or sickle. A relic or fetish called the spear of Mars was kept in a sacrarium at the Regia, the former residence of the Kings of Rome.

The spear was said to move, tremble or vibrate at impending war or other danger to the state. When Mars is pictured as a peace-bringer, his spear is wreathed with laurel or other vegetation, as on the Altar of Peace (Ara Pacis).

Mars, the planet

The planet Mars was named for him, and in some allegorical and philosophical writings, the planet and the god are endowed with shared characteristics. Mars is the ruling planet of Aries and is exalted in Capricorn.

Astrologically speaking, Mars is associated with confidence and self-assertion, aggression, sexuality, energy, strength, ambition and impulsiveness. Mars governs sports, competitions and physical activities in general. Latin adjectives from the name of Mars are martius and martialis, from which derive English “martial” (as in “martial arts” or “martial law”) and personal names such as “Martin”. In Indian astrology, Mars is called Mangala and represents energy, confidence and ego.

Aries and Capricorn

The zodiac signs for the month of March are Pisces (until March 20) and Aries (March 21 onwards. Mars is the ruling planet of Aries and is exalted in Capricorn.

Apollo

Amongst the Hurrians and later Hittites Nergal was known as Aplu, a name derived from the Akkadian Apal Enlil, (Apal being the construct state of Aplu) meaning “the son of Enlil”, a title that was given to the god Nergal, who was linked to Shamash, Babylonian god of the Sun, and with the plague. Aplu may be related with Apaliunas who is considered to be the Hittite reflex of *Apeljōn, an early form of the name Apollo.

Apaliunas is attested in a Hittite language treaty as a protective deity of Wilusa, a major city of the late Bronze Age in western Anatolia described in 13th century BC Hittite sources as being part of a confederation named Assuwa. The city is often identified with the Troy of the Ancient Greek Epic Cycle.

Many modern archaeologists have suggested that Wilusa corresponds to an archaeological site in Turkey known as Troy VIIa, which was destroyed circa 1190 BC. Ilios and Ilion, which are alternate names for Troy in the Ancient Greek languages, are linked etymologically to Wilusa.

This identification by modern scholars has been influenced by the Chronicon (a chronology of mythical and Ancient Greece) written circa 380 AD by Eusebius Sophronius Hieronymus (also known as Saint Jerome). In addition, the modern Biga Peninsula, on which Troy VIIa is located, is now generally believed to correspond to both the Hittite placename Taruiša and the Troas or Troad of late antiquity.

Apaliunas is among the gods who guarantee a treaty drawn up about 1280 BCE between Alaksandu of Wilusa, interpreted as “Alexander of Ilios” and the great Hittite king, Muwatalli II. He is one of the three deities named on the side of the city. In Homer, Apollo is the builder of the walls of Ilium, a god on the Trojan side.

A Luwian etymology suggested for Apaliunas makes Apollo “The One of Entrapment”, perhaps in the sense of “Hunter”. Further east of the Luwian language area, a Hurrian god Aplu was a deity of the plague – bringing it, or, if propitiated, protecting from it – and resembles Apollo Smintheus, “mouse-Apollo” worshiped at Troy and Tenedos, who brought plague upon the Achaeans in answer to a Trojan prayer at the opening of Iliad.

As the patron of Delphi (Pythian Apollo), Apollo was an oracular god—the prophetic deity of the Delphic Oracle. Medicine and healing are associated with Apollo, whether through the god himself or mediated through his son Asclepius, yet Apollo was also seen as a god who could bring ill-health and deadly plague.

Apollo is one of the most important and complex of the Olympian deities in classical Greek and Roman religion and Greek and Roman mythology. Apollo is the son of Zeus and Leto. Apollo is known in Greek-influenced Etruscan mythology as Apulu.

His twin sister, the chaste huntress Artemis, is one of the most widely venerated of the Ancient Greek deities. Homer refers to her as Artemis Agrotera, Potnia Theron: “Artemis of the wildland, Mistress of Animals”. The Arcadians believed she was the daughter of Demeter.

Some scholars believe that the name, and indeed the goddess herself, was originally pre-Greek. Her Roman equivalent is Diana. the goddess of the hunt, the moon, and nature in Roman mythology, associated with wild animals and woodland, and having the power to talk to and control animals.

In the classical period of Greek mythology, Artemis was often described as the daughter of Zeus and Leto, and the twin sister of Apollo. She was the Hellenic goddess of the hunt, wild animals, wilderness, childbirth, virginity and protector of young girls, bringing and relieving disease in women; she often was depicted as a huntress carrying a bow and arrows.

The ideal of the kouros (a beardless, athletic youth), Apollo has been variously recognized as a god of music, truth and prophecy, healing, the sun and light, plague, poetry, and more. Amongst the god’s custodial charges, Apollo became associated with dominion over colonists, and as the patron defender of herds and flocks.

As the leader of the Muses (Apollon Musegetes) and director of their choir, Apollo functioned as the patron god of music and poetry. Hermes created the lyre for him, and the instrument became a common attribute of Apollo. Hymns sung to Apollo were called paeans.

In Hellenistic times, especially during the 3rd century BCE, as Apollo Helios he became identified among Greeks with Helios, Titan god of the sun, and his sister Artemis similarly equated with Selene, Titan goddess of the moon.

In Latin texts, on the other hand, Joseph Fontenrose declared himself unable to find any conflation of Apollo with Sol among the Augustan poets of the 1st century, not even in the conjurations of Aeneas and Latinus in Aeneid XII (161–215). Apollo and Helios/Sol remained separate beings in literary and mythological texts until the 3rd century CE.

Pluto

Pluto is the ruling planet of Scorpio and is exalted in Pisces. In Roman mythology, Pluto is the god of the underworld and of wealth. The alchemical symbol was given to Pluto on its discovery, three centuries after alchemical practices had all but disappeared. The alchemical symbol can therefore be read as spirit over mind, transcending matter. The symbols were chosen given the close association with Mars which has a similar symbol. Pluto is also associated with Tuesday, alongside Mars.

Astrologically speaking, Pluto is called “the great renewer”, and is considered to represent the part of a person that destroys in order to renew, through bringing buried, but intense needs and drives to the surface, and expressing them, even at the expense of the existing order.

A commonly used keyword for Pluto is “transformation”. It is associated with power and personal mastery, and the need to cooperate and share with another, if each is not to be destroyed. Pluto governs big business and wealth, mining, surgery and detective work, and any enterprise that involves digging under the surface to bring the truth to light.

Heimdall

Heimdall and his equals

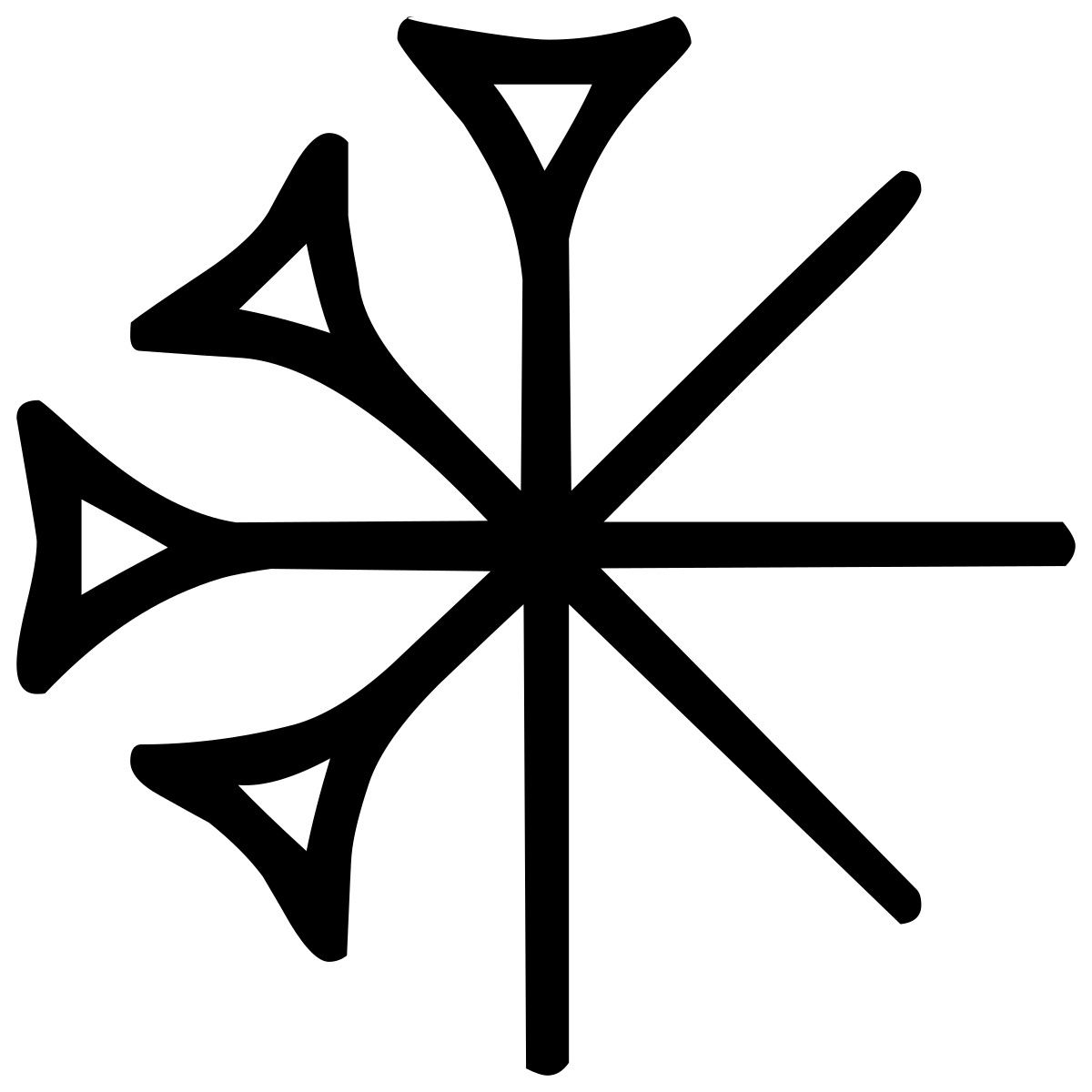

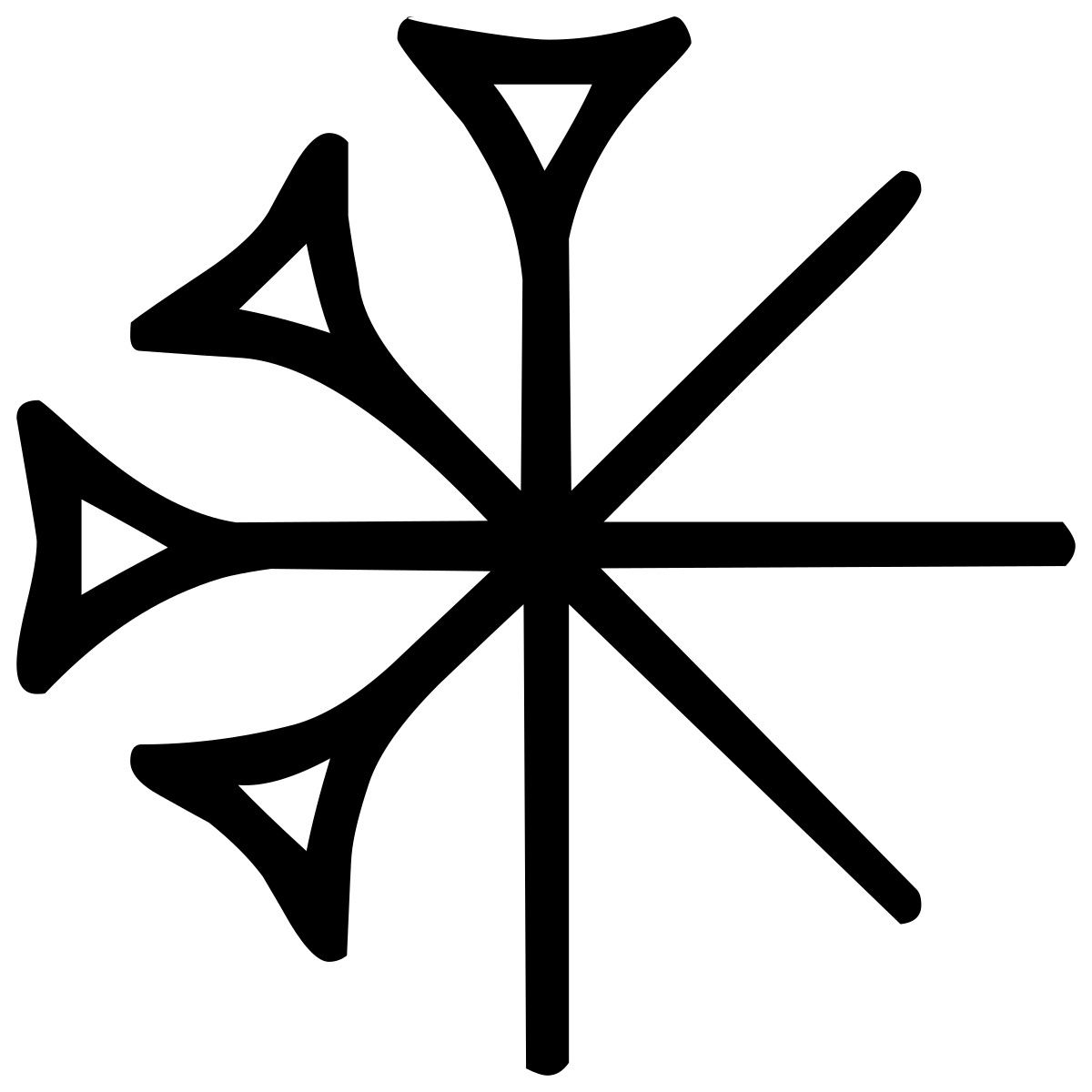

The Helm of Awe (Old Norse Ægishjálmr) is one of the most mysterious and powerful symbols in Norse mythology. Just looking at its form, without any prior knowledge of what that form symbolizes, is enough to inspire awe and fear: eight arms that look like spiked tridents radiate out from a central point, as if defending that central point by going on the offensive against any and all hostile forces that surround it.

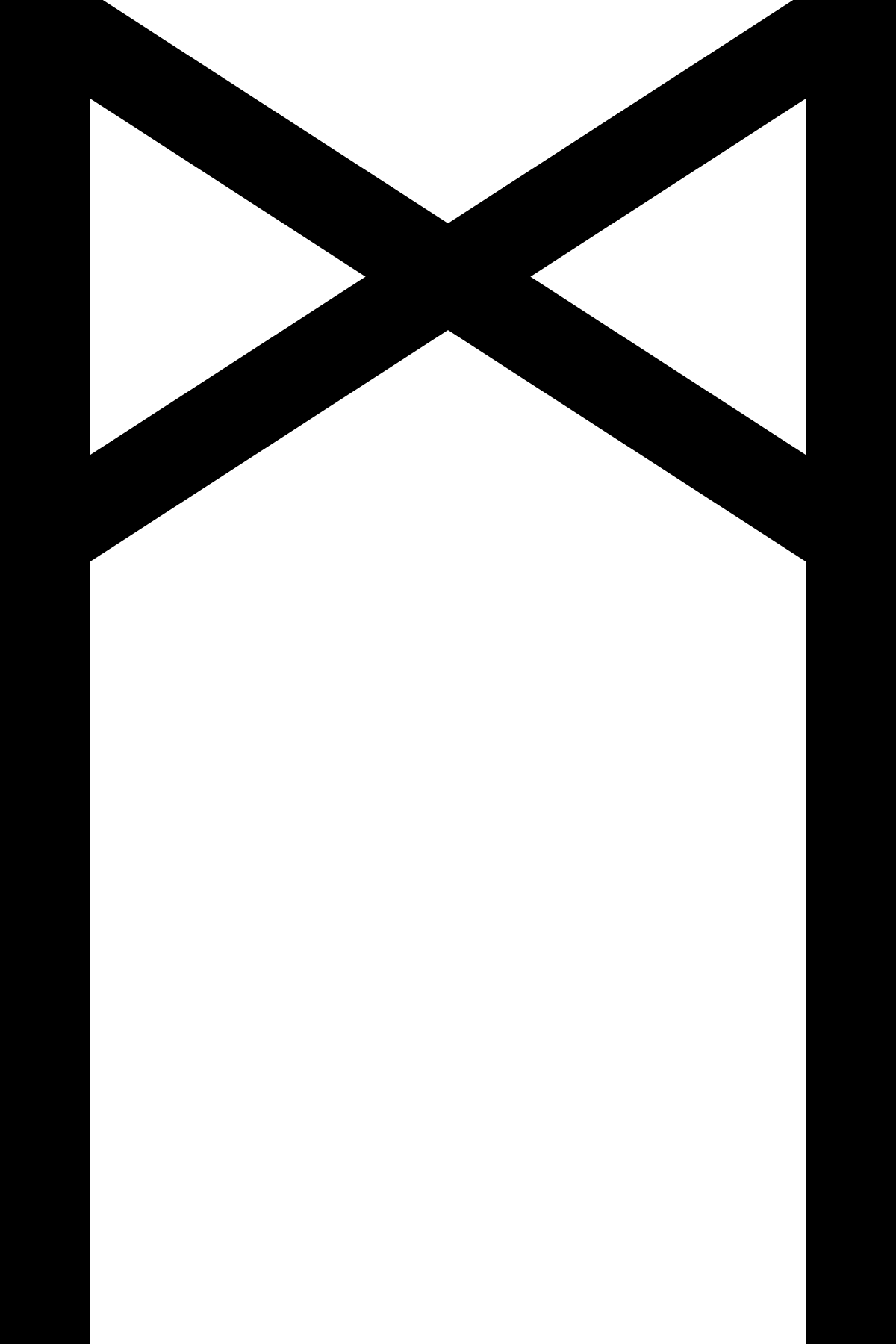

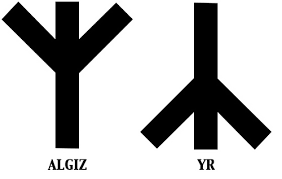

(D)Algiz rune – Heimdall

(D)Algiz (also Elhaz) and (T)Yr rune

Algiz – Rune Meaning Analysis

In Norse mythology, Heimdall’s role is guardian and protector. He is the watcher at the gate who guards the boundaries between the worlds and who charges all those entering and leaving with caution. He is best known for his horn, but his sword is just as important as it can be used for either offence or defence, depending upon the situation.

Heimdallr also appears as Heimdalr and Heimdali. The etymology of the name is obscure, but ‘the one who illuminates the world’ has been proposed. The prefix Heim- means world, the affix -dallr is of uncertain origin, perhaps it means pole (Yggdrasil), perhaps bright – He is described as “the brightest of the gods”.

Scholars have produced various theories about the nature of the god, including his apparent relation to rams, that he may be a personification of or connected to the world tree Yggdrasil, and potential Indo-European cognates.

He was known also by two other names – Hallinskidi and Gullintanni. Heimdall was the warder of the entrance to Asgard: the rainbow bridge called Bifröst (Bifrost or Bilrost). He dwelled in his hall Himinbjörg (Himinbiorg – “Cliff of the Hills” or “Heavenly Fall”), at the edge of Asgard, near Bifröst.

Heimdall had super-sharp eyesight and hearing. He was the never-sleeping watchman, whose duties to prevent giants from entering Asgard. His sword was called Heimdall’s Head (Hofund). He also watched and possessed the horn called Gjallahorn. When Heimdall blows Gjallahorn, it would to signify and warn the other gods of the coming of Ragnarök (Ragnarok).

Heimdall was the son of the Nine Waves (nine giantesses, who were sisters; this mean that Heimdall had nine mothers). The Nine Waves were the nine daughters of Aegir. The Nine mothers are the nine waves of the ocean, pictured as “ewes”, and the Heimdall is “the ram”, the ninth wave. Heimdall’s horn is part of that image, apparently, and he is pictured as either the father of the nine waves or as the child of the nine waves, or both.

Heimdall created the three races of mankind: the serfs, the peasants, and the warriors. It is interesting to note why Heimdall fathered them, and not Odin as might be expected. Furthermore, Heimdall is in many attributes identical with Tyr. As Heimdall, the world tree reach from the sky to the underworld so do Nergal (Tyr) as a skylord, but at the same time a god of the underworld.

Algiz rune

Algiz (also Elhaz) is the name conventionally given to the “z-rune” ᛉ of the Elder Futhark runic alphabet. Its transliteration is z, understood as a phoneme of the Proto-Germanic language, the terminal *z continuing Proto-Indo-European terminal *s. Usualy a long “Z”, as in “buzz” is the pronunciation of this rune, but occasionally “R”, or even “M”, although there are other runes that represent these sounds too.

In the physical world, Algiz is a weapon of protection such as a sword, protecting with a sharp edge. In the spiritual world, Algiz represents a faith or belief in the gods or a god and that which is beyond our five physical senses.

The form of the rune resembles an outstretched hand, probably representing the hand of Tyr, which was sacrificed for the safety of the universe. Algiz represents the divine plan as set apart from individual affairs, even in spite of human concerns entirely.

Algiz (also called Elhaz) is a powerful rune, because it represents the divine might of the universe. The white elk was a symbol to the Norse of divine blessing and protection to those it graced with sight of itself.

Algiz is the rune of higher vibrations, the divine plan and higher spiritual awareness. The energy of Algiz is what makes something feel sacred as opposed to mundane. It represents the worlds of Asgard (gods of the Aesir), Ljusalfheim (The Light Elves) and Vanaheim (gods of the Vanir), all connecting and sharing energies with our world, Midgard.

The rune is a ward of protection, a shield against negativity. The urge to defend or protect others, a guardianship, that banishing or warding off of a negative presence. Opening the pathways to connection to the gods, an awakening. A sign to follow your instincts to keep hold of a position earned.

It represents your power to protect yourself and those around you. It also connotes the thrill and joy of a successful hunt. You are in a very enviable position right now, because you are able to maintain what you have built and reach your current goals.

The symbol itself could represent the upper branches of Yggdrasil, a flower opening to receive the sun (Sowilo is the next rune in the futhark after all,) the antlers of the elk (the elk-sedge), the Valkyrie and her wings, or the invoker stance common to many of the world’s priests and shamans.

It also looks like the outstreched branches of a tree or the footprint of a bird, such as a crow or raven. In a very contemporary context, the symbol could be powerfully equated to a satellite dish reaching toward the heavens and communicating with the gods and other entities throughout this and other worlds.

Algiz is the supreme rune of healing and protection. The upright position of this rune was used to denote the date of birth on Viking tombstones. The inverted form was likewise used to give the date of death.

Protection, a shield. The protective urge to shelter oneself or others. Defense, warding off of evil, shield, guardian. Connection with the gods, awakening, higher life. It can be used to channel energies appropriately. Follow your instincts. Keep hold of success or maintain a position won or earned. Algiz Reversed: or Merkstave: Hidden danger, consumption by divine forces, loss of divine link. Taboo, warning, turning away, that which repels.

When Algiz appears in a reading merkstave, it is a warning to proceed with caution and to not act rashly or hastily. You may be vulnerable to hostile influences at this time and need to concentrate on building your strength physically, emotionally and spiritually before moving forward.

Reversed, Algiz is a sign that hidden dangers lie ahead. Ill-health may be about to strike. It may also represent a warning to get a second (or third) opinion before proceeding with anything of importance (eg. signing contracts etc).

Because this specific phoneme was lost at an early time, the Elder Futhark rune underwent changes in the medieval runic alphabets. In the Anglo-Saxon futhorc it retained its shape, but it was given the sound value of Latin x.

The name of the Anglo-Saxon rune ᛉ is variously recorded as eolx, ilcs, ilix, elux, eolhx. Manuscript tradition gives its sound value as Latin x, i.e. /ks/, or alternatively as il, or yet again as “l and x”.

This is a secondary development, possibly due to runic manuscript tradition, and there is no known instance of the rune being used in an Old English inscription. In Proto-Norse and Old Norse, the Germanic *z phoneme developed into an R sound, perhaps realized as a retroflex approximant [ɻ], which is usually transcribed as ʀ.

In the earliest inscriptions, the rune invariably has its standard Ψ-shape. From the 5th century or so, the rune appears optionally in its upside-down variant which would become the standard Younger Futhark yr shape.

There are also other graphical variants; for example, the Charnay Fibula has a superposition of these two variants, resulting in an “asterisk” shape (ᛯ). The 9th-century abecedarium anguliscum in Codex Sangallensis 878 shows eolh as a peculiar shape, as it were a bindrune of the older ᛉ with the Younger Futhark ᛦ, resulting in an “asterisk” shape similar to ior ᛡ.

The shape of the rune may be derived from that a letter expressing /x/ in certain Old Italic alphabets (𐌙), which was in turn derived from the Greek letter Ψ, which had the value of /kʰ/ (rather than /ps/) in the Western Greek alphabet.

The Elder Futhark rune ᛉ is conventionally called Algiz or Elhaz, from the Common Germanic word for “elk”. However, it is suggested that the original name of the rune could have been Common Germanic *algiz (‘Algie’), meaning not “elk” but “protection, defence”.

Manuscript tradition gives its sound value as Latin x, i.e. /ks/, or alternatively as il, or yet again as “l and x”. It has benn suggested that the eolhx (etc.) may have been a corruption of helix, and that the name of the rune may be connected to the use of elux for helix to describe the constellation of Ursa major (as turning around the celestial pole).

An earlier suggestion is that the earliest value of this rune was the labiovelar /hw/, and that its name may have been hweol “wheel”. In the 6th and 7th centuries, the Elder Futhark began to be replaced by the Younger Futhark in Scandinavia. By the 8th century, the Elder Futhark was extinct, and Scandinavian runic inscriptions were exclusively written in Younger Futhark.

The sound was written in the Younger Futhark using the Yr rune ᛦ, the Algiz rune turned upside down, from about the 7th century. This phoneme eventually became indistinguishable from the regular r sound in the later stages of Old Norse, at about the 11th or 12th century.

The Yr rune ᛦ is a rune of the Younger Futhark. Its common transliteration is a small capital ʀ. The shape of the Yr rune in the Younger Futhark is the inverted shape of the Elder Futhark rune (ᛉ). Its name yr (“yew”) is taken from the name of the Elder Futhark Eihwaz rune.

In recent Futhark rune Algiz symbolize the man, which ultimately is just an extension of its meaning of “life” is linked elk, deer, an animal very important for the people of Northern Ireland and the Celtic tradition , represents the God Cernunnos, god of fertility and abundance.

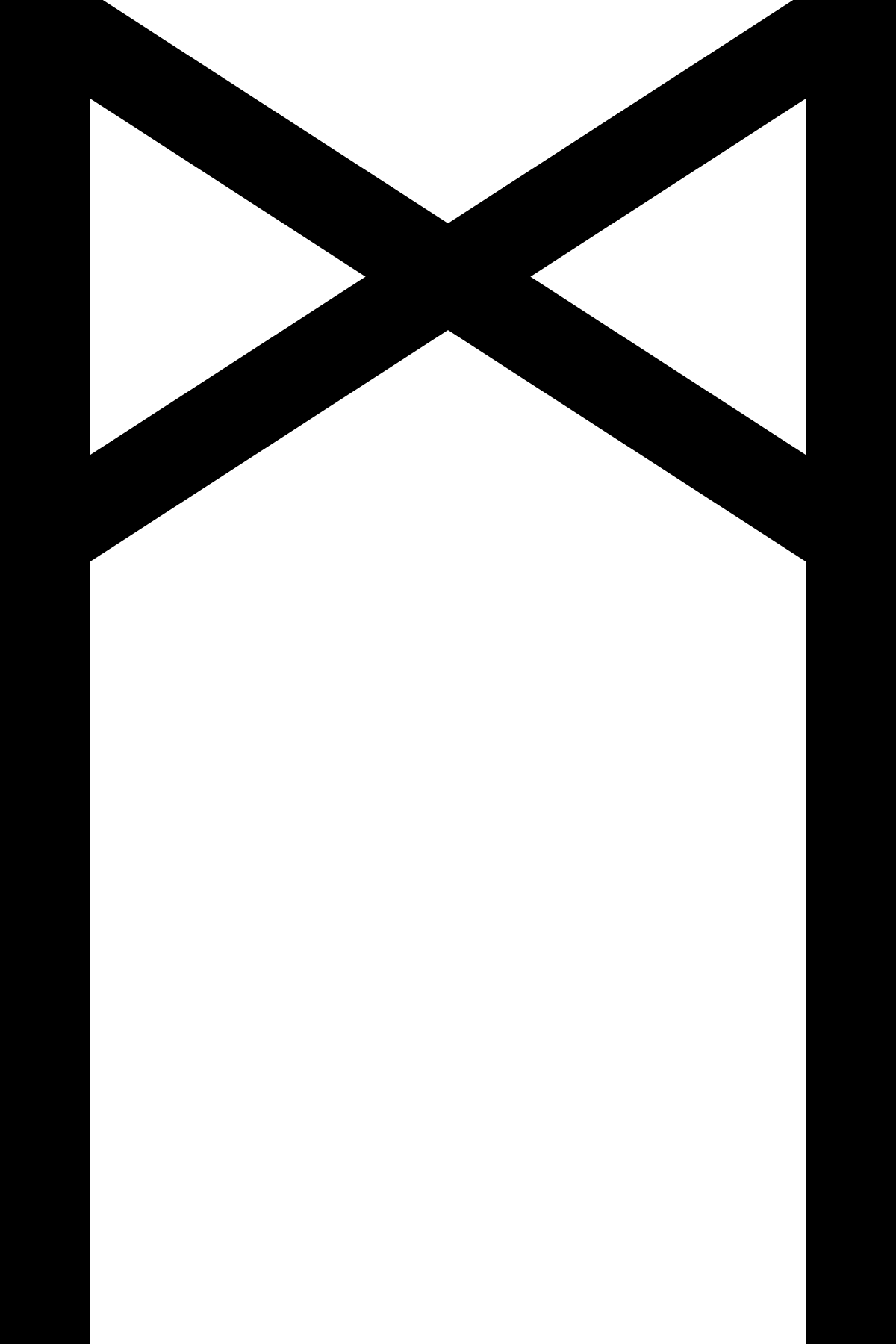

Independently, the shape of the Elder Futhark Algiz rune reappears in the Younger Futhark Maðr rune ᛘ, continuing the Elder Futhark ᛗ rune *Mannaz. *Mannaz is the conventional name of the m-rune ᛗ of the Elder Futhark. It is derived from the reconstructed Common Germanic word for “man”, *mannaz.

Younger Futhark ᛘ is maðr (“man”). It took up the shape of the algiz rune ᛉ, replacing Elder Futhark ᛗ. As its sound value and form in the Elder Futhark indicate, it is derived from the letter M (𐌌) in the Old Italic alphabets, ultimately from the Greek letter Mu (μ).

Algiz Rune

Algiz Rune

Tyr

Týr is a Germanic god associated with law and heroic glory in Norse mythology, portrayed as one-handed. One handed, Tyr is worshipped as a pinnacle of righteousness, called upon for valor in battle, balance in law, and the fortitude to face the impossible.

As the cloud of war blackens the world, and fear grips the people, Tyr is stooped by the weight of expectation. With blade in hand, he takes the field. For he is Courage, honor, and justice. Tiw was equated with Mars in the interpretatio germanica. Tuesday is “Tīw’s Day” (also in Alemannic Zischtig from zîes tag), translating dies Martis.

Old Norse Týr, literally “god”, plural tívar “gods”, comes from Proto-Germanic *Tīwaz (cf. Old English Tīw, Old High German Zīo), which continues Proto-Indo-European *deiwós “celestial being, god” (cf. Welsh duw, Latin deus, Lithuanian diẽvas, Sanskrit dēvá, Avestan daēvō (false) “god”, Serbo-Croatian div giant). And *deiwós is based in *dei-, *deyā-, *dīdyā-, meaning ‘to shine’.

It is assumed that Tîwaz was overtaken in popularity and in authority by both Odin and Thor at some point during the Migration Age, as Odin shares his role as God of war. Dyēus is believed to have been the chief deity in the religious traditions of the prehistoric Proto-Indo-European societies. Part of a larger pantheon, he was the god of the daylit sky, and his position may have mirrored the position of the patriarch or monarch in society.

Although some of the more iconic reflexes of Dyeus are storm deities, such as Zeus and Jupiter, this is thought to be a late development. The deity’s original domain was over the daylight sky, and indeed reflexes emphasise this connection to light: Tiwaz (Stem: Tiwad-) was the Luwian Sun-god.

Tiwas rune

Tiwaz is a warrior rune named after the god Tyr who is the Northern god of law and justice. It is a rune that represents the balance and justice ruled from a higher rationality. It represents the sacrifice of the individual (self) for the well-being of the whole (society).

Honor, justice, leadership and authority. Analysis, rationality. Knowing where one’s true strengths lie. Willingness to self-sacrifice. Victory and success in any competition or in legal matters.

Tiwaz Reversed or Merkstave: One’s energy and creative flow are blocked. Mental paralysis, over-analysis, over-sacrifice, injustice, imbalance. Strife, war, conflict, failure in competition. Dwindling passion, difficulties in communication, and possibly separation.

Tiwaz Rune

Mannaz rune

Mannus, according to the Roman writer Tacitus, was a figure in the creation myths of the Germanic tribes. According to Tacitus Mannus was the son of Tuisto and the progenitor of the three Germanic tribes Ingaevones, Herminones and Istvaeones. The names Mannus and Tuisto/Tuisco seem to have some relation to Proto-Germanic Mannaz, “man” and Tiwaz, “Tyr, the god”.

Mannaz represents the fundamental human qualities of all the men and the women: it is the common experience. The archetype of the humans, considered as the reflection of every thing in the existence, is represented by its shape which still evokes by its geometry the idea of the mutual support. Its legs, connected by Gebo’s cross, evoke a stiff shape identical to the stability acquired thanks to the solidarity.

Mannaz is the rune of the accomplished Man. The most positive human qualities are associated with Mannaz, this rune symbolizes the hope in a bigger accomplishment of Humanity and about its best qualities such as the kindness and the generosity. Mannaz also represents the social order necessary to every person to realize his or her human potential.

The trident is the weapon of Poseidon, or Neptune, the god of the sea in classical mythology. In Hindu mythology it is the weapon of Shiva, known as trishula (Sanskrit for “triple-spear”). In Greek, Roman, and Hindu mythology, the trident is said to have the power of control over the ocean.

Neptune

Neptune was the god of freshwater and the sea in Roman religion. He is the counterpart of the Greek god Poseidon. Salacia, the goddess of saltwater, was his wife. As his wife, Salacia bore Neptune three children, the most celebrated being Triton, whose body was half man and half fish. She is identified with the Greek goddess Amphitrite, who is the wife of Poseidon and the queen of the sea.

In the Greek-influenced tradition, Neptune was the brother of Jupiter and Pluto; the brothers presided over the realms of Heaven, the earthly world, and the Underworld.

Neptune was also considered the legendary progenitor god of a Latin stock, the Faliscans, who called themselves Neptunia proles. In this respect he was the equivalent of Mars, Janus, Saturn and even Jupiter among Latin tribes. Salacia would represent the virile force of Neptune.

Among ancient sources Arnobius provides important information about the theology of Neptune: he writes that according to Nigidius Figulus Neptune was considered one of the Etruscan Penates, together with Apollo, the two deities being credited with bestowing Ilium or Troy situated in the southwest mouth of the Dardanelles strait and northwest of Mount Ida with its immortal walls.

Trident

A trident is a three-pronged spear. It is used for spear fishing and historically as a polearm. The trident is the weapon of Poseidon, or Neptune, the god of the sea in classical mythology. In Hindu mythology it is the weapon of Shiva, known as trishula (Sanskrit for “triple-spear”).

The word “trident” comes from the French word trident, which in turn comes from the Latin word tridens or tridentis: tri “three” and dentes “teeth”. Sanskrit trishula is compound of tri (“three”) + ṣūla (“thorn”). The Greek equivalent is “tríaina”, from Proto-Greek “trianja” (“threefold”).

In Greek, Roman, and Hindu mythology, the trident is said to have the power of control over the ocean. In relation to its fishing origins, the trident is associated with Poseidon, the god of the sea in Greek mythology, and his Roman counterpart Neptune. In Roman myth, Neptune also used a trident to create new bodies of water and cause earthquakes. A good example can be seen in Gian Bernini’s Neptune and Triton.

In Greek myth, Poseidon used his trident to create water sources in Greece and the horse. Poseidon, as well as being god of the sea, was also known as the “Earth Shaker” because when he struck the earth in anger he caused mighty earthquakes and he used his trident to stir up tidal waves, tsunamis and sea storms.

In Hindu legends and stories Shiva, a Hindu God who holds a trident in his hand, uses this sacred weapon to fight off negativity in the form of evil villains. The trident is also said to represent three gunas mentioned in Indian vedic philosophy namely sāttvika, rājasika, and tāmasika. The trishula of the Hindu god Shiva. A weapon of South-East Asian (particularly Thai) depiction of Hanuman, a character of Ramayana.

In religious Taoism, the trident represents the Taoist Trinity, the Three Pure Ones. In Taoist rituals, a trident bell is used to invite the presence of deities and summon spirits, as the trident signifies the highest authority of Heaven.

Paredrae

Salacia is known as the goddess of springs, ruling over the springs of highly mineralized waters. Salacia is represented as a beautiful nymph, crowned with seaweed, either enthroned beside Neptune or driving with him in a pearl shell chariot drawn by dolphins, sea-horses (hippocamps) or other fabulous creatures of the deep, and attended by Tritons and Nereids.

Venilia, in Roman mythology, is a deity associated with the winds and the sea. She and Salacia are the paredrae, entities who pair or accompany a god, of Neptune. According to Virgil and Ovid she was a nymph, the sister of Amata, and the wife of Janus (or Faunus) with whom she had three children, Turnus, Juturna, and Canens.

In the view of Dumézil, Neptune’s two paredrae Salacia and Venilia represent the overpowering and the tranquil aspects of water, both natural and domesticated: Salacia would impersonate the gushing, overbearing waters and Venilia the still or quietly flowing waters. Dumézil’s interpretation has though been varied as he also stated that the jolt implied by Salacia’s name, the attitude to be salax lustful, must underline a feature characteristic of the god.

Salacia and Venilia have been discussed by scholars both ancient and modern. Varro connects the first to salum, sea, and the second to ventus, wind. Festus writes of Salacia that she is the deity that generates the motion of the sea. While Venilia would cause the waves to come to the shore Salacia would cause their retreating towards the high sea.

Mermaid

In folklore, a mermaid is an aquatic creature with the head and upper body of a female human and the tail of a fish. Mermaids appear in the folklore of many cultures worldwide, including the Near East, Europe, Africa and Asia.

Mermaids are sometimes associated with perilous events such as floods, storms, shipwrecks and drownings. In other folk traditions (or sometimes within the same tradition), they can be benevolent or beneficent, bestowing boons or falling in love with humans.

The word mermaid is a compound of the Old English mere (sea), and maid (a girl or young woman). The male equivalent of the mermaid is the merman, also a familiar figure in folklore and heraldry. Although traditions about and sightings of mermen are less common than those of mermaids, they are generally assumed to co-exist with their female counterparts.

Pisces is the twelfth astrological sign in the Zodiac. It spans 330° to 360° of celestial longitude. Under the tropical zodiac the sun transits this area on average between February 18 and March 20, and under the sidereal zodiac, the sun transits this area between approximately March 13 and April 13. The symbol of the fish is derived from the ichthyocentaurs, who aided Aphrodite when she was born from the sea.

Virgo is the sixth astrological sign in the Zodiac. It spans the 150-180th degree of the zodiac. Under the tropical zodiac, the Sun transits this area on average between August 23 and September 22, and under the sidereal zodiac, the sun transits the constellation of Virgo from September 17 to October 17.

The constellation Virgo has multiple different origins depending on which mythology is being studied. The symbol of the maiden is based on Astraea. Pisces has been called the “dying god,” where its sign opposite in the night sky is Virgo, or, the Virgin Mary.

Most myths generally view Virgo as a virgin/maiden with heavy association with wheat. In Greek and Roman mythology they relate the constellation to Demeter, mother of Persephone, or Proserpina in Roman, the goddess of the harvest.

The first stories of mermaids appeared in ancient Assyria c. 1000 BC., in which the goddess Atargatis, the chief goddess of northern Syria in Classical Antiquity, transformed herself into a mermaid out of shame for accidentally killing her human lover.

Primarily Atargatis was a goddess of fertility, but, as the baalat (“mistress”) of her city and people, she was also responsible for their protection and well-being. As Ataratheh, doves and fish were considered sacred to her: doves as an emblem of the Love-Goddess, and fish as symbolic of the fertility and life of the waters.

Atargatis is seen as a continuation of Bronze Age goddesses. At Ugarit, cuneiform tablets attest the three great Canaanite goddesses:ʾAṭirat, described as a fecund “Lady Goddess of the Sea”, who is identified with Asherah, Anat, the war-like virgin goddess, andʿAțtart, the goddess of love.

These shared many traits with each other and may have been worshipped in conjunction or separately during 1500 years of cultural history. Cognates of Ugaritic ʿAțtart include Phoenician ʿAštart – hellenized as Astarte –, Old Testament Hebrew ʿAštoreth, and Himyaritic ʿAthtar. Compare the cognate Akkadian form Ištar.

Asherah in ancient Semitic religion, is a mother goddess who appears in a number of ancient sources. Sources from before 1200 BC almost always credit Athirat with her full title “Lady Athirat of the Sea” or as more fully translated “she who treads on the sea”. The name is understood by various translators and commentators to be from the Ugaritic root ʾaṯr “stride”, cognate with the Hebrew root ʾšr, of the same meaning.

Asherah is identified as the queen consort of the Sumerian god Anu, and Ugaritic El, the oldest deities of their respective pantheons, as well as Yahweh, the god of Israel and Judah. She is equated with the native Egyptian goddess Hathor. Among the Hittites this goddess appears as Asherdu(s) or Asertu(s), the consort of Elkunirsa (“El the Creator of Earth”).

Athirat in Akkadian texts appears as Ashratum (or, Antu), the wife of Anu, the God of Heaven. In contrast, ʿAshtart is believed to be linked to the Mesopotamian goddess Ishtar who is sometimes portrayed as the daughter of Anu while in Ugaritic myth, ʿAshtart is one of the daughters of El, the West Semitic counterpart of Anu.

Pisces

Neptune is the ruling planet of Pisces and is exalted in Cancer. The Pisces is the twelfth astrological sign in the Zodiac. It spans 330° to 360° of celestial longitude. Under the tropical zodiac the sun transits this area on average between February 18 and March 20, and under the sidereal zodiac, the sun transits this area between approximately March 13 and April 13. Its glyph is taken directly from Neptune’s trident, symbolizing the curve of spirit being pierced by the cross of matter.

Today, the First Point of Aries, or the vernal equinox, is in the Pisces constellation. Pisces are the mutable water sign of the zodiac. They represent emotion, intuition, imagination, escapism, romance, and impressionism. The astrological symbol shows the two fishes captured by a string, typically by the mouth or the tails. The fish are usually portrayed swimming in opposite directions; this represents the duality within the Piscean nature.

The age of Pisces began c. 1 AD and will end c. 2150 AD. With the story of the birth of Christ coinciding with this date, many Christian symbols for Christ use the astrological symbol for Pisces, the fishes.

The story of the birth of Christ is said to be a result of the spring equinox entering into the Pisces, as the Savior of the World appeared as the Fisher of Men. This parallels the entering into the Age of Pisces. Pisces has been called the “dying god,” where its sign opposite in the night sky is Virgo, or, the Virgin Mary.

Etymology

The etymology of Latin Neptunus is unclear and disputed. The ancient grammarian Varro derived the name from nuptus i.e. “covering” (opertio), with a more or less explicit allusion to the nuptiae, “marriage of Heaven and Earth”.

Among modern scholars Paul Kretschmer proposed a derivation from IE *neptu- “moist substance”. Similarly Raymond Bloch supposed it might be an adjectival form in -no from *nuptu-, meaning “he who is moist”.

Georges Dumézil though remarked words deriving root *nep- are not attested in IE languages other than Vedic and Avestan. He proposed an etymology that brings together Neptunus with Vedic and Avestan theonyms Apam Napat, Apam Napá and Old Irish theonym Nechtan, all meaning descendant of the waters.

By using the comparative approach the Indo-Iranian, Avestan and Irish figures would show common features with the Roman historicised legends about Neptune. Dumézil thence proposed to derive the nouns from IE root *nepot-, “descendant, sister’s son”.

More recently, in his lectures delivered on various occasions in the 1990s, German scholar Hubert Petersmann proposed an etymology from IE rootstem *nebh- related to clouds and fogs, plus suffix -tu denoting an abstract verbal noun, and adjectival suffix -no which refers to the domain of activity of a person or his prerogatives.

IE root *nebh-, having the original meaning of “damp, wet”, has given Sanskrit nábhah, Hittite nepis, Latin nubs, nebula, German Nebel, Slavic nebo etc. The concept would be close to that expressed in the name of Greek god Uranus, derived from IE root *hwórso-, “to water, irrigate” and *hworsó-, “the irrigator”. This etymology would be more in accord with Varro’s.

Nepet is considered a hydronymic toponym of pre Indoeuropean origin widespread in Europe and from an appellative meaning “damp wide valley, plain”, cognate with the pre-Greek word for “wooded valley”.

The god of springs

Neptune was likely associated with fresh water springs before the sea. Like Poseidon, Neptune was worshipped by the Romans also as a god of horses, under the name Neptunus Equester, a patron of horse-racing.

It has been argued that Indo-European people, having no direct knowledge of the sea as they originated from inland areas, reused the theology of a deity originally either chthonic or wielding power over inland freshwaters as the god of the sea.

This feature has been preserved particularly well in the case of Neptune who was definitely a god of springs, lakes and rivers before becoming also a god of the sea, as is testified by the numerous findings of inscriptions mentioning him in the proximity of such locations.

In the earlier times it was the god Portunus or Fortunus who was thanked for naval victories, but Neptune supplanted him in this role by at least the first century BC when Sextus Pompeius called himself “son of Neptune.”

Servius the grammarian also explicitly states Neptune is in charge of all the rivers, springs and waters. He also is the lord of horses because he worked with Minerva to make the chariot.

He may find a parallel in Irish god Nechtan, master of the well from which all the rivers of the world flow out and flow back to. Poseidon on the other hand underwent the process of becoming the main god of the sea at a much earlier time, as is shown in the Iliad.

Fertility deity and divine ancestor

Preller, Fowler, Petersmann and Takács attribute to the theology of Neptune broader significance as a god of universal worldly fertility, particularly relevant to agriculture and human reproduction. Thence they interpret Salacia as personifying lust and Venilia as related to venia, the attitude of ingraciating, attraction, connected with love and desire for reproduction.

Neptune might have been an ancient deity of the cloudy and rainy sky in company with and in opposition to Zeus/Jupiter, god of the clear bright sky. Besides Zeus/Jupiter, (rooted in IE *dei(h) to shine, who originally represented the bright daylight of fine weather sky), the ancient Indo-Europeans venerated a god of heavenly damp or wet as the generator of life.

This fact would be testified by Hittite theonyms nepišaš (D)IŠKURaš or nepišaš (D)Tarhunnaš “the lord of sky wet”, that was revered as the sovereign of Earth and men. Even though over time this function was transferred to Zeus/Jupiter who became also the sovereign of weather, reminiscences of the old function survived in literature.

The indispensability of water for its fertilizing quality and its strict connexion to reproduction is universal knowledge. The sexual and fertility significance of both Salacia and Venilia is implicated on the grounds of the context of the cults of Neptune, of Varro’s interpretation of Salacia as eager for sexual intercourse and of the connexion of Venilia with a nymph or Venus.

Similar to Caelus, he would be the father of all living beings on Earth through the fertilising power of rainwater. This hieros gamos of Neptune and Earth would be reflected in literature. The virile potency of Neptune would be represented by Salacia (derived from salax, salio in its original sense of salacious, lustful, desiring sexual intercourse, covering).

Salacia would then represent the god’s desire for intercourse with Earth, his virile generating potency manifesting itself in rainfall. While Salacia would denote the overcast sky, the other character of the god would be reflected by his other paredra Venilia, representing the clear sky dotted with clouds of good weather.

The theonym Venilia would be rooted in a not attested adjective *venilis, from IE root *ven(h) meaning to love, desire, realised in Sanskrit vánati, vanóti, he loves, Old Island. vinr friend, German Wonne, Latin Venus, venia.

The deity of the cloudy and rainy sky

Developing his understanding of the theonym as rooted in IE *nebh, it has been proposed that the god would be an ancient deity of the cloudy and rainy sky in company with and in opposition to Zeus/Jupiter, god of the clear bright sky. Similar to Caelus, he would be the father of all living beings on Earth through the fertilising power of rainwater.

This hieros gamos of Neptune and Earth would be reflected in literature, e.g. in pater Neptunus. The virile potency of Neptune would be represented by Salacia (derived from salax, salio in its original sense of salacious, lustful, desiring sexual intercourse, covering).

Salacia would then represent the god’s desire for intercourse with Earth, his virile generating potency manifesting itself in rainfall. While Salacia would denote the overcast sky, the other character of the god would be reflected by his other paredra Venilia, representing the clear sky dotted with clouds of good weather.

The theonym Venilia would be rooted in a not attested adjective *venilis, from IE root *ven(h) meaning to love, desire, realised in Sanskrit vánati, vanóti, he loves, Old Island. vinr friend, German Wonne, Latin Venus, venia. Reminiscences of this double aspect of Neptune would be “uterque Neptunus”.

In Petersmann’s conjecture, besides Zeus/Jupiter, (rooted in IE *dei(h) to shine, who originally represented the bright daylight of fine weather sky), the ancient Indo-Europeans venerated a god of heavenly damp or wet as the generator of life. This fact would be testified by Hittite theonyms nepišaš (D)IŠKURaš or nepišaš (D)Tarhunnaš “the lord of sky wet”, that was revered as the sovereign of Earth and men.

Even though over time this function was transferred to Zeus/Jupiter who became also the sovereign of weather, reminiscences of the old function survived in literature. The indispensability of water for its fertilizing quality and its strict connexion to reproduction is universal knowledge.

Hadad, Adad, Haddad (Akkadian) or Iškur (Sumerian) was the storm and rain god in the Northwest Semitic and ancient Mesopotamian religions. He was attested in Ebla as “Hadda” in c. 2500 BCE. From the Levant, Hadad was introduced to Mesopotamia by the Amorites, where he became known as the Akkadian (Assyrian-Babylonian) god Adad.

Adad and Iškur are usually written with the logogram dIM—the same symbol used for the Hurrian god Teshub. Hadad was also called “Pidar”, “Rapiu”, “Baal-Zephon”, or often simply Baʿal (Lord), but this title was also used for other gods. The bull was the symbolic animal of Hadad. He appeared bearded, often holding a club and thunderbolt while wearing a bull-horned headdress.

Hadad was equated with the Greek god Zeus; the Roman god Jupiter, as Jupiter Dolichenus; the Indo-European Nasite Hittite storm-god Teshub; the Egyptian god Amun; the Rigvedic god Indra. In Akkadian, Adad is also known as Ramman (“Thunderer”) cognate with Aramaic Rimmon, which was a byname of Hadad. Ramman was formerly incorrectly taken by many scholars to be an independent Assyrian-Babylonian god later identified with the Hadad.

Though originating in northern Mesopotamia, Adad was identified by the same Sumerogram dIM that designated Iškur in the south. His worship became widespread in Mesopotamia after the First Babylonian Dynasty. A text dating from the reign of Ur-Ninurta characterizes Adad/Iškur as both threatening in his stormy rage and generally life-giving and benevolent.

The form Iškur appears in the list of gods found at Shuruppak but was of far less importance, probably partly because storms and rain were scarce in Sumer and agriculture there depended on irrigation instead. The gods Enlil and Ninurta also had storm god features that decreased Iškur’s distinctiveness. He sometimes appears as the assistant or companion of one or the other of the two.

When Enki distributed the destinies, he made Iškur inspector of the cosmos. In one litany, Iškur is proclaimed again and again as “great radiant bull, your name is heaven” and also called son of Anu, lord of Karkara; twin-brother of Enki, lord of abundance, lord who rides the storm, lion of heaven.

In other texts Adad/Iškur is sometimes son of the moon god Nanna/Sin by Ningal and brother of Utu/Shamash and Inanna/Ishtar. Iškur is also sometimes described as the son of Enlil. The bull was portrayed as Adad/Iškur’s sacred animal starting in the Old Babylonian period (the first half of the 2nd millennium BCE).

Adad/Iškur’s consort (both in early Sumerian and the much later Assyrian texts) was Shala, a goddess of grain, who is also sometimes associated with the god Dagan. She was also called Gubarra in the earliest texts. The fire god Gibil (named Gerra in Akkadian) is sometimes the son of Iškur and Shala.

He is identified with the Anatolian storm-god Teshub, whom the Mitannians designated with the same Sumerogram dIM. Occasionally Adad/Iškur is identified with the god Amurru, the god of the Amorites.

Adad/Iškur presents two aspects in the hymns, incantations, and votive inscriptions. On the one hand he is the god who, through bringing on the rain in due season, causes the land to become fertile, and, on the other hand, the storms that he sends out bring havoc and destruction.

He is pictured on monuments and cylinder seals (sometimes with a horned helmet) with the lightning and the thunderbolt (sometimes in the form of a spear), and in the hymns the sombre aspects of the god on the whole predominate. His association with the sun-god, Shamash, due to the natural combination of the two deities who alternate in the control of nature, leads to imbuing him with some of the traits belonging to a solar deity.

Descriptions of Adad starting in the Kassite period and in the region of Mari emphasize his destructive, stormy character and his role as a fearsome warrior deity, in contrast to Iškur’s more peaceful and pastoral character. Shamash and Adad became in combination the gods of oracles and of divination in general.

In religious texts, Ba‘al/Hadad is the lord of the sky who governs the rain and thus the germination of plants with the power to determine fertility. He is the protector of life and growth to the agricultural people of the region. The absence of Ba‘al causes dry spells, starvation, death, and chaos.

Nechtan

The name could ultimately be derived from the Proto-Indo-European root *nepot- “descendant, sister’s son”, or, alternatively, from nebh- “damp, wet”. Another etymology suggests that Nechtan is derived from Old-Irish necht “clean, pure and white”, with a root -neg “to wash”, from IE neigᵘ̯- “to wash”.

As such, the name would be closely related mythological beings, who were dwelling near wells and springs: English neck (from Anglosaxon nicor), Swedish Näck, German Nixe and Dutch nikker, meaning “river monster, water spirit, crocodile, hippopotamus”, hence Old-Norse nykr “water spirit in the form of a horse”.

In Etruscan mythology, Nethuns was the god of wells, later expanded to all water, including the sea. According to Georges Dumézil the name Nechtan is perhaps cognate with that of the Romano-British god Nodens or the Roman god Neptunus, and the Persian and Vedic gods sharing the name Apam Napat.

In Irish mythology, the Well of Nechtan (also called the Well of Coelrind, Well of Connla, and Well of Segais) is one of a number of Otherworldly wells that are variously depicted as “The Well of Wisdom”, “The Well of Knowledge” and the source of some of the rivers of Ireland. The well is the home to the salmon of wisdom, and surrounded with hazel trees, which also signify knowledge and wisdom.

Nechtan or Nectan became a common Celtic name and a number of historical or legendary figures bear it. Nechtan was a frequent name for Pictish kings.

In Norse mythology, Mímisbrunnr (Old Norse “Mímir’s well”) is a well associated with the being Mímir, located beneath the world tree Yggdrasil. The well contains “wisdom and intelligence” and “the master of the well is called Mimir.

Mimir is full of learning because he drinks of the well from the horn Giallarhorn (Old Norse “yelling horn” or “the loud sounding horn”), a horn associated with the god Heimdallr and the wise being Mímir. Using Gjallarhorn, Heimdallr drinks from the well and thus is himself wise.

Urðarbrunnr (Old Norse “Well of Urðr”; either referring to a Germanic concept of fate—urðr—or the norn named Urðr) is a well in Norse mythology. Urðarbrunnr is attested in the Poetic Edda, compiled in the 13th century from earlier traditional sources, and the Prose Edda, written in the 13th century by Snorri Sturluson.

In both sources, the well lies beneath the world tree Yggdrasil, and is associated with a trio of norns (Urðr, Verðandi, and Skuld). In the Prose Edda, Urðarbrunnr is cited as one of three wells existing beneath three roots of Yggdrasil that reach into three distant, different lands; the other two wells being Hvergelmir, located beneath a root in Niflheim, and Mímisbrunnr, located beneath a root near the home of the frost jötnar.

In the Poetic Edda, Urðarbrunnr is mentioned in stanzas 19 and 20 of the poem Völuspá, and stanza 111 of the poem Hávamál. In stanza 19 of Völuspá, Urðarbrunnr is described as being located beneath Yggdrasil, and that Yggdrasil, an ever-green ash-tree, is covered with white mud or loam.

Stanza 20 describes that three norns (Urðr, Verðandi, and Skuld) “come from” the well, here described as a “lake”, and that this trio of norns then “set down laws, they chose lives, for the sons of men the fates of men.”

Apzu

The name “Nethuns” is likely cognate with that of the Celtic god Nechtan and the Persian and Vedic gods sharing the name Apam Napat, perhaps all based on the Proto-Indo-European word *népōts “nephew, grandson.” In the Rig Veda, Apām Napāt (Lord Varuna) is the angel of rain. Apam Napat created all existential beings.

Apām Napāt in Sanskrit mean “son of waters” and grandson of Apah and Apąm Napāt in Avestan means “Fire on Water”. Sanskrit and Avestan napāt (“grandson”) are cognate to Latin nepōs and English nephew, but the name Apām Napāt has also been compared to Etruscan Nethuns and Celtic Nechtan and Roman Neptune. Apam Napat has a golden splendour and is said to be kindled by the cosmic waters.

The Abzu or Apsu (ZU.AB; Sumerian: abzu; Akkadian: apsû), also called engur (Sumerian: engur; Akkadian: engurru – lit., ab=’water’ zu=’deep’), was the name for fresh water from underground aquifers which was given a religious fertilising quality in Sumerian and Akkadian mythology.

Lakes, springs, rivers, wells, and other sources of fresh water were thought to draw their water from the abzu. In this respect, in Sumerian and Akkadian mythology it referred to the primeval sea below the void space of the underworld (Kur) and the earth (Ma) above.

Abzu is depicted as a deity only in the Babylonian creation epic, the Enûma Elish, taken from the library of Assurbanipal (c 630 BCE) but which is about 500 years older. In this story, he was a primal being made of fresh water and a lover to another primal deity, Tiamat, who was a creature of salt water.

The Enuma Elish begins: “When above the heavens did not yet exist nor the earth below, Apsu the freshwater ocean was there, the first, the begetter, and Tiamat, the saltwater sea, she who bore them all; they were still mixing their waters, and no pasture land had yet been formed, nor even a reed marsh.”

This resulted in the birth of the younger gods, who later murder Apsu in order to usurp his lordship of the universe. Enraged, Tiamat gives birth to the first dragons, filling their bodies with “venom instead of blood”, and made war upon her treacherous children, only to be slain by Marduk, the god of Storms, who then forms the heavens and earth from her corpse.

Enki

Enki (Sumerian: dEN.KI(G) is the Sumerian god of water, knowledge (gestú), mischief, crafts (gašam), and creation (nudimmud). He was later known as Ea in Akkadian and Babylonian mythology. He was originally patron god of the city of Eridu, but later the influence of his cult spread throughout Mesopotamia and to the Canaanites, Hittites and Hurrians.

Enki was associated with the southern band of constellations called stars of Ea, but also with the constellation AŠ-IKU, the Field (Square of Pegasus). Pegasus is a constellation in the northern sky, named after the winged horse Pegasus in Greek mythology.

The Babylonian constellation IKU (field) had four stars of which three were later part of the Greek constellation Hippos (Pegasus). In ancient Persia, Pegasus was depicted by al-Sufi as a complete horse facing east, unlike most other uranographers, who had depicted Pegasus as half of a horse, rising out of the ocean.

In the city of Eridu, Enki’s temple was known as E-abzu (house of the cosmic waters) and was located at the edge of a swamp, an abzu. Certain tanks of holy water in Babylonian and Assyrian temple courtyards were also called abzu (apsû). Typical in religious washing, these tanks were similar to Judaism’s mikvot, the washing pools of Islamic mosques, or the baptismal font in Christian churches.

The Sumerian god Enki (Ea in the Akkadian language) was believed to have lived in the abzu since before human beings were created. His wife Damgalnuna, his mother Nammu, his advisor Isimud and a variety of subservient creatures, such as the gatekeeper Lahmu, also lived in the abzu.

In the later Babylonian epic Enûma Eliš, Abzu, the “begetter of the gods”, is inert and sleepy but finds his peace disturbed by the younger gods, so sets out to destroy them. His grandson Enki, chosen to represent the younger gods, puts a spell on Abzu “casting him into a deep sleep”, thereby confining him deep underground. Enki subsequently sets up his home “in the depths of the Abzu.” Enki thus takes on all of the functions of the Abzu, including his fertilising powers as lord of the waters and lord of semen.

In another even older tradition, Nammu, the goddess of the primeval creative matter and the mother-goddess portrayed as having “given birth to the great gods,” was the mother of Enki, and as the watery creative force, was said to preexist Ea-Enki.

In Sumerian mythology, Nammu (also Namma, spelled ideographically dNAMMA = dENGUR) was a primeval goddess, corresponding to Tiamat in Babylonian mythology. She was the Goddess sea (Engur) that gave birth to An (heaven) and Ki (earth) and the first gods, representing the Apsu, the fresh water ocean that the Sumerians believed lay beneath the earth, the source of life-giving water and fertility in a country with almost no rainfall.

Nammu is the goddess who “has given birth to the great gods”. It is she who has the idea of creating mankind, and she goes to wake up Enki, who is asleep in the Apsu, so that he may set the process going. Benito states “With Enki it is an interesting change of gender symbolism, the fertilising agent is also water, Sumerian “a” or “Ab” which also means “semen”. In one evocative passage in a Sumerian hymn, Enki stands at the empty riverbeds and fills them with his ‘water'”.

The main temple to Enki was called E-abzu, meaning “abzu temple” (also E-en-gur-a, meaning “house of the subterranean waters”), a ziggurat temple surrounded by Euphratean marshlands near the ancient Persian Gulf coastline at Eridu. It was the first temple known to have been built in Southern Iraq.

Four separate excavations at the site of Eridu have demonstrated the existence of a shrine dating back to the earliest Ubaid period, more than 6,500 years ago. Over the following 4,500 years, the temple was expanded 18 times, until it was abandoned during the Persian period.

On this basis Thorkild Jacobsen has hypothesized that the original deity of the temple was Abzu, with his attributes later being taken by Enki over time. P. Steinkeller believes that, during the earliest period, Enki had a subordinate position to a goddess (possibly Ninhursag), taking the role of divine consort or high priest, later taking priority.

The Enki temple had at its entrance a pool of fresh water, and excavation has found numerous carp bones, suggesting collective feasts. Carp are shown in the twin water flows running into the later God Enki, suggesting continuity of these features over a very long period.

These features were found at all subsequent Sumerian temples, suggesting that this temple established the pattern for all subsequent Sumerian temples. “All rules laid down at Eridu were faithfully observed”.

Enki and later Ea were apparently depicted, sometimes, as a man covered with the skin of a fish, and this representation, as likewise the name of his temple E-apsu, “house of the watery deep”, points decidedly to his original character as a god of the waters.

Beginning around the second millennium BCE, he was sometimes referred to in writing by the numeric ideogram for “40”, occasionally referred to as his “sacred number”. The planet Mercury, associated with Babylonian Nabu (the son of Marduk) was, in Sumerian times, identified with Enki.

A large number of myths about Enki have been collected from many sites, stretching from Southern Iraq to the Levantine coast. He is mentioned in the earliest extant cuneiform inscriptions throughout the region and was prominent from the third millennium down to Hellenistic times.

The exact meaning of his name is uncertain: the common translation is “Lord of the Earth”. The Sumerian En is translated as a title equivalent to “lord” and was originally a title given to the High Priest. Ki means “earth”, but there are theories that ki in this name has another origin, possibly kig of unknown meaning, or kur meaning “mound”.

Early royal inscriptions from the third millennium BCE mention “the reeds of Enki”. Reeds were an important local building material, used for baskets and containers, and collected outside the city walls, where the dead or sick were often carried. This links Enki to the Kur or underworld of Sumerian mythology.

The name Ea is allegedly Hurrian in origin while others claim that his name ‘Ea’ is possibly of Semitic origin and may be a derivation from the West-Semitic root *hyy meaning “life” in this case used for “spring”, “running water”. In Sumerian E-A means “the house of water”, and it has been suggested that this was originally the name for the shrine to the god at Eridu.

It has also been suggested that the original non-anthropomorphic divinity at Eridu was not Enki but Abzu. The emergence of Enki as the divine lover of Ninhursag, and the divine battle between the younger Igigi divinities and Abzu, saw the Abzu, the underground waters of the Aquifer, becoming the place in which the foundations of the temple were built.

Enki was the keeper of the divine powers called Me, the gifts of civilization. He is often shown with the horned crown of divinity. Considered the master shaper of the world, god of wisdom and of all magic, Enki was characterized as the lord of the Abzu (Apsu in Akkadian), the freshwater sea or groundwater located within the earth.

On the Adda Seal, Enki is depicted with two streams of water flowing into each of his shoulders: one the Tigris, the other the Euphrates. Alongside him are two trees, symbolizing the male and female aspects of nature. He is shown wearing a flounced skirt and a cone-shaped hat. An eagle descends from above to land upon his outstretched right arm. This portrayal reflects Enki’s role as the god of water, life, and replenishment.

Enki/Ea is essentially a god of civilization, wisdom, and culture. He was also the creator and protector of man, and of the world in general. It is, however, as the third figure in the triad (the two other members of which were Anu and Enlil) that Ea acquires his permanent place in the pantheon. To him was assigned the control of the watery element, and in this capacity he becomes the shar apsi; i.e. king of the Apsu or “the deep”.

The Apsu was figured as the abyss of water beneath the earth, and since the gathering place of the dead, known as Aralu, was situated near the confines of the Apsu, he was also designated as En-Ki; i.e. “lord of that which is below”, in contrast to Anu, who was the lord of the “above” or the heavens.

The consort of Ea, known as Ninhursag, Ki, Uriash Damkina, “lady of that which is below”, or Damgalnunna, “big lady of the waters”, originally was fully equal with Ea, but in more patriarchal Assyrian and Neo-Babylonian times plays a part merely in association with her lord.

Generally, however, Enki seems to be a reflection of pre-patriarchal times, in which relations between the sexes were characterised by a situation of greater gender equality. In his character, he prefers persuasion to conflict, which he seeks to avoid if possible.

Ninhursag

In Sumerian religion, Ninḫursaĝ (DNIN-ḪUR.SAG) was a mother goddess of the mountains, and one of the seven great deities of Sumer. She is principally a fertility goddess. Temple hymn sources identify her as the “true and great lady of heaven” (possibly in relation to her standing on the mountain) and kings of Sumer were “nourished by Ninhursag’s milk”.

Sometimes her hair is depicted in an omega shape and at times she wears a horned head-dress and tiered skirt, often with bow cases at her shoulders. Frequently she carries a mace or baton surmounted by an omega motif or a derivation, sometimes accompanied by a lion cub on a leash. She is the tutelary deity to several Sumerian leaders.

In the text ‘Creator of the Hoe’, she completed the birth of mankind after the heads had been uncovered by Enki’s hoe. In creation texts, Ninmah (another name for Ninhursag) acts as a midwife whilst the mother goddess Nammu makes different kinds of human individuals from lumps of clay at a feast given by Enki to celebrate the creation of humankind.

Her symbol, resembling the Greek letter omega Ω, has been depicted in art from approximately 3000 BC, although more generally from the early second millennium BC. The omega symbol is associated with the Egyptian cow goddess Hathor, and may represent a stylized womb. The symbol appears on very early imagery from Ancient Egypt. Hathor is at times depicted on a mountain, so it may be that the two goddesses are connected.

Cybele (perhaps “Mountain Mother”) is an Anatolian mother goddess; she may have a possible precursor in the earliest neolithic at Çatalhöyük in Anatolia, where statues of plump women, sometimes sitting, have been found in excavations dated to the 6th millennium BC and identified by some as a mother goddess.

Hursag

Hursag (ḪUR.SAĜ) is a Sumerian term variously translated as meaning “mountain”, “hill”, “foothills” or “piedmont”. Thorkild Jacobsen extrapolated the translation in his later career to mean literally, “head of the valleys”. Some scholars also identify hursag with an undefined mountain range or strip of raised land outside the plain of Mesopotamia.

In a myth variously entitled by Samuel Noah Kramer as “The Deeds and Exploits of Ninurta” and later Ninurta Myth Lugal-e by Thorkild Jacobsen, Hursag is described as a mound of stones constructed by Ninurta after his defeat of a demon called Asag.

Ninurta’s mother Ninlil (DNIN.LÍL”lady of the open field” or “Lady of the Wind”), the consort goddess of Enlil, visits the location after this great victory. In return for her love and loyalty, Ninurta gives Ninlil the hursag as a gift. Her name is consequentially changed from Ninlil to Ninhursag or the “mistress of the Hursag”.

The hursag is described here in a clear cultural myth as a high wall, levee, dam or floodbank, used to restrain the excess mountain waters and floods caused by the melting snow and spring rain. The hursag is constructed with Ninurta’s skills in irrigation engineering and employed to improve the agriculture of the surrounding lands, farms and gardens where the water had previously been wasted.

Apkallu

Adapa, the first of the Mesopotamian seven sages (apkallu[a]), was a mythical figure who unknowingly refused the gift of immortality. The story is first attested in the Kassite period (14th century BC), in fragmentary tablets from Tell el-Amarna, and from Assur, of the late second millennium BC.

Adapa was a mortal man from a godly lineage, a son of Ea (Enki in Sumerian), the god of wisdom and of the ancient city of Eridu, who brought the arts of civilization to that city (from Dilmun, according to some versions).

Adapa is often identified as an adviser to the mythical first (antediluvian) king of Eridu, Alulim. In addition to his advisory duties, he served as a priest and exorcist, and upon his death took his place among the Seven Sages or Apkallū. (Apkallu “sage”, comes from Sumerian AB.GAL “great water”, a reference to Adapa the first sage’s association with water).

Mesopotamian myth tells of seven antediluvian sages, who were sent by Ea, the wise god of Eridu, to bring the arts of civilisation to humankind. They were seen as fish-like men who emerged from the sweet water Abzu. The first of these, Adapa, also known as Uan, the name given as Oannes by Berossus, introduced the practice of the correct rites of religious observance as priest of the E’Apsu temple, at Eridu.

The sages are described in Mesopotamian literature as ‘pure parādu-fish, probably carp, whose bones are found associated with the earliest shrine, and still kept as a holy duty in the precincts of Near Eastern mosques and monasteries. Adapa as a fisherman was iconographically portrayed as a fish-man composite.

According to the myth, human beings were initially unaware of the benefits of culture and civilization. The god Enki (or Ea) sent from Dilmun (or Abzu) amphibious half-fish, half-human divine creatures, who emerged from the oceans to live with the early human beings and teach them the arts and other aspects of civilization such as writing, law, temple and city building and agriculture. According to the Temple Hymn of Ku’ara, all seven sages are said to have originally belonged to the city of Eridu.

These creatures are known as the Apkallu. They are credited with giving mankind the Me (moral code), the crafts, and the arts, and therefore referred to at times with the epithet ‘Craftsmen’. They remained with human beings after teaching them the ways of civilization, and served as advisors to the antediluvian kings. After the Flood, Marduk banished them back to Abzu.

Apkallu and human beings were presumably capable of conjugal relationships since after the flood, the myth states that four Apkallu appeared. These were part human and part Apkallu. These Apkallus are said to have committed various transgressions which angered the gods.

These seeming negative deeds of the later Apkallu and their roles as wise councillors has led some scholars to equate them with the nephilim of Genesis 6:4. After these four post-diluvian Apkallus came the first completely human advisers, who were called ummanu.

Gilgamesh, the mythical king of Uruk, is said to be the first king to have had an entirely human adviser. In recent times, scholars have also suggested the Apkallu are the Raphaim and are the model for the biblical world human beings and flood survivors such as Enoch, the ancestor of Noah.